"25 for 25" — a love letter to McSweeney's

a new essay from SSL contributor Abigail Oswald, in our ongoing celebration of short stories of the 21st century

This month and last (and probably here and there throughout the rest of the year), we’re spotlighting some of our favorite stories of the century (so far).

When I pitched to the Short Story, Long contributors putting together a list of some of their favorite stories of the century, or any other ideas they may have in celebration of short stories from the last 25 years, Abby pretty immediately and excitedly pitched an essay celebrating McSweeney’s.

A spotlight on McSweeney’s One Hundred and Forty Five Stories in a Small Box, which was probably one of my first exposures to flash fiction… would end up talking about how formative Eggers and McSweeney’s were for me in exploring the possibilities of form!

I just as immediately and excitedly loved the idea. In almost every interview I’ve ever done, I’ve talked about how formative and life-changing McSweeney’s was for me. In fact,

just interviewed me last week and I said as much:In college, I worked at Barnes & Noble, and often specifically in magazines. One day we were unboxing new issues of, like, New Yorker and Entertainment Weekly and Cosmo and Cat Fancy, and just all of those kinds of magazine rack mags, and then we opened a box and it was full of maybe just 12 or 16 copies of McSweeney's #4. I'd never seen anything like it! It was a small box, inside of which was a bunch of individual stories, each as its own pamphlet. I thought it was just so cool and interesting and weird. I was pretty immediately intrigued and interested and won over. This would have been 2000.

From there, I found the McSweeney's website, and I bought every single one of the first 4 or 5 or 10 books McSweeney's published. And it just opened up this world of contemporary writing that felt new and exciting and often playful and funny and cool. I think, for people around my age, if you got into writing, McSweeney's was probably incredibly important to that.

So excited to get to feature this essay from Abby!

—Aaron

Little Risks

A love letter to McSweeney’s and the infinite possibilities of storytelling

I’m pretty sure I first discovered the box of stories at BookPeople, but perhaps that memory is invented. There’s something magical about this unlabeled box and the strange drawings that adorn it. It seems just as likely that I might’ve found it perched at the end of a row of snacks in a vending machine, tucked into the hollow of a tree, or abandoned in a phone booth bearing a note that warns READ AT YOUR OWN PERIL—methods of distribution reaching only the most curious (and perhaps mildly predisposed to believe in magic).

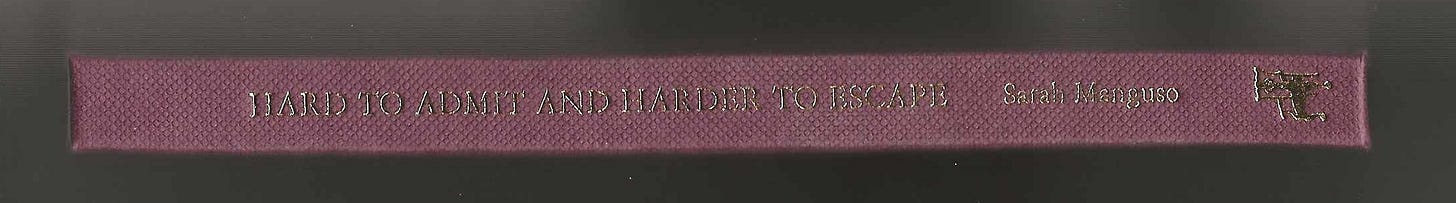

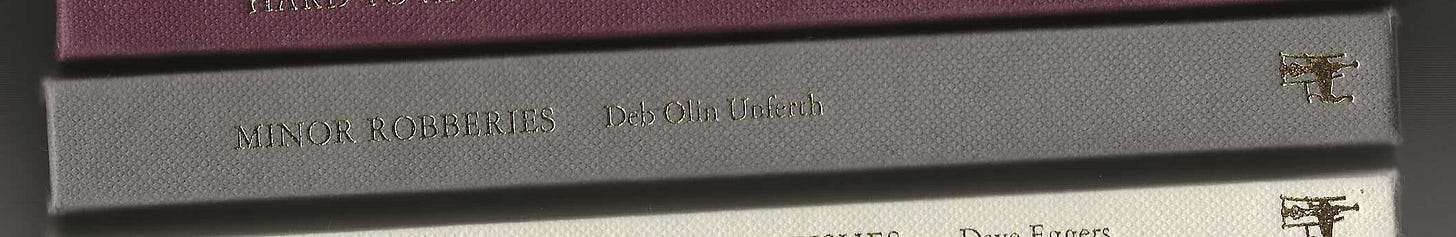

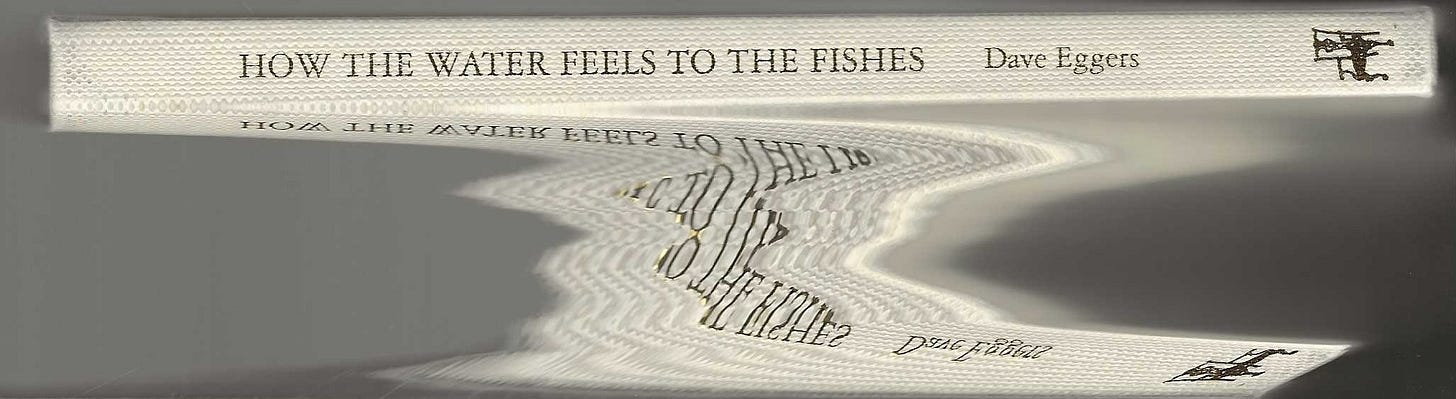

One Hundred and Forty Five Stories in a Small Box contains three prose experiments in book form: Sarah Manguso’s Hard to Admit and Harder to Escape, Deb Olin Unferth’s Minor Robberies, and Dave Eggers’ How the Water Feels to the Fishes. I’ve returned to this box of stories many times over the years, at varying twists and forks of my own writing journey. What I’ve found is that each of the three books contains a series of tiny lessons that continue to reinvent narrative for me over time, providing a lens through which I can glimpse new possibilities for art and life.

When I look at the last twenty-five years in books, it feels impossible to ignore McSweeney’s impact. An independent publishing house founded by Dave Eggers in 1998, McSweeney’s has devoted more than a quarter of a century to reimagining the possibilities of narrative via literary journals, books, the Internet Tendency, and more. If rules exist for writing at all, McSweeney’s suggests, they exist for the purpose of being shredded and then painstakingly woven back together in a new pattern, washed in scalding water and then tumble-dried against instruction, or vaguely acknowledged only in the moment they are gleefully leapt over.

More than anything, I’m grateful to McSweeney’s for writing that is at once exploratory and exemplary. I’m writing about three of the stories contained in this box not just in praise of their authors’ individual skills, but because of the life-changing question each one posed for me as a budding writer:

If we did this, what can you do?

I. SARAH, or, Writing is Magic!

Hard to Admit and Harder to Escape was the first book by Sarah Manguso I ever read, and I’ve kept up with her work ever since. Whether she’s writing flash fiction, an elegy, or three hundred arguments, Manguso is a master of precise language. As a reader, I’m continually struck by the sense that Manguso is saying exactly what she intends to say, conjuring the scene or thought or feeling in her reader’s mind with consistent, crystalline clarity.

In Hard to Admit, Manguso’s stories are titled with numbers. “On the last day of the year I write myself a letter and seal it in an envelope and write on the envelope OPEN 12/31,” “43” begins. But now that the letter is written, the narrator spends the ensuing year anticipating opening it. When the time comes, the narrator opens the envelope and finds that they remember the contents of the letter entirely. The act of writing created not a disconnected message beamed from a past self to a future one, in the end, but a throughline that the present self carried between the two. Writing meant remembering.

From my first read I was gripped by the idea that a simple handwritten letter could hold such power. But of course, it makes all the sense in the world: writing things down is a way of focusing one’s attention. As we write, we can redirect our own thoughts; we can change our own minds. The mere act of listing past events and future hopes alters the course of the narrator’s thinking going forward. On the page we can rewrite the past, shape the world around us; we can even change the future.

Even if the result is never shared with another living soul, the solitary act of writing is powerful and revelatory entirely on its own. It is, as Manguso evidences here, a way of connecting people across time. Sometimes that person is just another version of you.

II. DEB, or, Everything Is Connected.

A previous version of me dog-eared a handful of pages in Deb Olin Unferth’s Minor Robberies to return to in the future. Controversial, I know(!), and yet across my personal library, these tell-tale flaps offer a reliable trail of clues for returning to words and ideas that once resonated with me. Will my future self feel the same way?

Unferth’s “Once She Once Was” explores the nature of the connection between past and future selves, hinging on personality changes that occur in the wake of the protagonist’s decision to quit smoking—a conclusion that initially seems positive, but fuels the protagonist’s suspicions. Has this single change created a ripple effect of additional changes which have then transformed her into a different person entirely—someone she didn’t want to be?

“…perhaps the act of not smoking one day changed her slightly and then not smoking another day changed her slightly again and each day was like that, small change on top of small change,” the narrator suggests, “until slowly she became a person who didn’t mind not dating people she didn’t like, for example, and each day she was a different person, if only slightly, until one day she was this, her current self, a nonsmoker, the person she didn’t want to be, which doesn’t seem so bad now, in fact, seems better.” In just a few paragraphs, the story raises a profound question: How far can I evolve along the continuum of change and still feel like “me”?

It’s only now, as I’m writing about this story—immediately after writing about Manguso’s story—that I see the extent to which they’re linked. But so often it goes like this—I’m drawn to certain stories, and only through the act of writing about them do I come to understand their connections. We grow and evolve as people and the art we love comes along for the ride, offering up fresh meaning all the time, if we just look closely.

More than a decade after this story was published in Minor Robberies, Unferth selected my own writing for a Best Microfiction anthology—a micro-meditation on King Kong composed in a series of Google searches. It’s still pretty joyously surreal to me, the idea that someone whose writing first introduced me to the flash form later read one of my own small experiments years later, let alone chose it for an anthology. But that’s the world we’re lucky enough to create in, and this is exactly why I love writing as much as I do. Connections like this happen every day, all the time.

III. DAVE, or, What If?

I first read A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius in between bouts of mind-numbing standardized testing, a juxtaposition that I think the author would enjoy. I had the distinct sensation that I was using opposite parts of my brain—one activity training me to fill in circles with the correct answer and write neatly within the lines, while the other presented questions like, “What if we advised the reader which sections to skip if they’re pressed for time?” or the classic “What if this page featured a drawing of a stapler?”

In many ways Eggers has long been a model for the kind of writer I want to be—open to play and experimentation on the page while amplifying others and encouraging creativity within his community. From the beginning I’ve admired the way his imagination connects these pursuits, a constant joyous wondering aloud: What if?

One of my favorite stories in Eggers’ How the Water Feels to the Fishes imagines a reality where actual people organize the programming for your dreams, like a film festival. “The people who do your dreams are like the people in your life who give very thoughtful gifts,” the narrator of “Thoughtful That Way” informs us. “The people who organize your nighttime dreams are paying close attention to the things you see and hear during the day.” There is always a direct line between your dreams and the things that happen while you are awake, because the people who do your dreams program accordingly.

In a funny way, Eggers’ version of events almost makes more sense than what actually happens to us when we sleep—our bodies creating strange stories for us entirely of their own accord. But that’s what a story can be, I’ve found: a way of literally making sense—DIY logic built out of your own connections. An experiment born out of devoting yourself entirely to a single question: What if?

There is a way in which everything I have ever written is an answer to that question. (My own Short Story, Long story was an exploration of “What if you found your doppelganger on the internet?”) I hope that every writer understands they have total freedom to explore these what-ifs from the moment they pick up a pen. Sometimes I think it’s Eggers who made me realize that I didn’t need to ask for permission at all. That there was nothing to wait for. I could just start writing, find the answer for myself.

It’s kind of wild to think about how much a personal creative trajectory often comes down to which books you picked up at the school library or a local independent bookstore, or, as previously suggested, in a vending machine or from the trunk of a mysterious tree. I know I wouldn’t be the writer I am today without One Hundred and Forty Five Stories in a Small Box, without McSweeney’s. I just wouldn’t.

McSweeney’s gave me an early taste of the extent to which writing can be one great big happy experiment. Play is by no means something we’re obligated to grow out of! What if a story was a pencil, revised as the pencil was sharpened? What if a story was a balloon, and the reader had to blow it up in order to read it? What if stories came in tin lunchboxes, or a stack of assorted mail? It’s true that a story can exist in as many forms as we humans can imagine—and so many of mine never would have existed without McSweeney’s.

In the intervening years since first discovering One Hundred and Forty Five Stories in a Small Box, I’ve written things that take the form of search histories and outlines and one very long sentence containing a gratuitous number of my beloved em dashes. I’ve collaged dictionary definitions and incorporated text messages; I submitted my work for publication in a vending machine of memories. I shred and weave the rules, I wash them and I tumble dry, I close my eyes and leap. And through all of this, if I ever hesitate, I just ask myself: What if?

Somewhere along the line I made the decision to live with the perspective that every work of art might hold the potential to change my life. (Even—or maybe especially—some words on a page.) If you buy into the idea that art can change you, rewire you as a person, send you down a different path, it means taking little risks every day. Each story you start offers one more what-if. Every time you walk into the movie theater becomes a chance to change your life. The world can change you, and maybe if you pick up a pen, you can change it back. It can be a little scary, opening yourself to that unrelenting possibility.

But to live a life shaped irrevocably by art—isn’t that kind of magic?

McSweeney’s is one of the many publishers affected by the NEA grant terminations. Drop your favorite from McSweeney’s library in the comments and consider buying one of their books or literary journals today!

If you haven’t already, go read Abigail’s great story, “You Are Still Allowed Your Dreams,” in our archives!

You Are Still Allowed Your Dreams by Abigail Oswald

I was fourteen when I found my doppelganger on the internet.

At first, my brain failed to process the person in the photograph as someone other than myself; it was as if a memory had been plucked from my mind and pasted onto the screen before me. Here was a picture I did not remember taking, in a posture I had never assumed, wearing clothes I had never owned, in a room I had never entered.