You Are Still Allowed Your Dreams by Abigail Oswald

"I was fourteen when I found my doppelganger on the internet... Here was a picture I did not remember taking, in a posture I had never assumed, wearing clothes I had never owned..."

I’ve reread Abby’s “You Are Still Allowed Your Dreams” at least twice in the last few days, heading toward today’s publication, and with every reread I’m wowed anew at what I fell in love with on my first read and wowed, too, by something wholly new.

Something I’m especially awed by is the way the story twists and turns, growing and building on itself, finding something “surprising yet inevitable” around every new turn while so perfectly capturing so many different emotions and feelings and stages of life along the way. There is the perfect time capsule of being 14 years old and discovering the early internet — message boards and blogs and the precursors to social media, and how it all felt new and exciting and awkward and mysterious, all laid atop the newness and excitement and awkwardness and mysterious of being a teenager. And then the story jumps forward, and just as perfectly captures that stage in your late 20s/early 30s of starting to find your way in the world, gaining independence and confidence but also not yet being where you want to be. “There were some mornings, after walking out the front door and closing it behind me, I felt gravity might release its hold on me for good and I might simply ascend into space, floating there in the ether, that much closer to the sun and stars.” the story says, and every time I read it I think, yes, yes, exactly.

And as if either of those components would not be enough for me to fall in love with, much less a story that can so adeptly do both, there is also the magic and the mystery of this narrator’s doppelganger looming over the story in a way that feels so perfect, so intriguing and exciting.

I say some version of this with every story, and with every story mean it as genuinely as possible, but I’m so excited to share this one! I hope some of you as in love with it as I have.

—Aaron Burch

I was fourteen when I found my doppelganger on the internet.

At first, my brain failed to process the person in the photograph as someone other than myself; it was as if a memory had been plucked from my mind and pasted onto the screen before me. Here was a picture I did not remember taking, in a posture I had never assumed, wearing clothes I had never owned, in a room I had never entered.

And yet, for a moment I was certain that I was looking into a mirror.

I absorbed the honeyed locks of her long, wavy hair in a state of muted shock. The white silk blouse draped perfectly on her slim frame. The corner of her mouth tilted upward, offering a hint of my smile.

I looked down at my oversized t-shirt, the threadbare drawstring pajama bottoms that featured many tiny iterations of a sassy cartoon rabbit. I was searching for a contrast to steady me, rationality for what I’d seen.

I know now that I was on the precipice of stepping through a portal to another life. I could have closed the window and severed the tie. But in the end, I could not deny the insistent gnaw of my curiosity. And so—without a thought to the consequences, without a single look back at what I might be leaving behind—I moved forward.

*

An explanation, however implausible, presented itself in the coming days: She was a girl who lived in a country thousands of miles away who looked exactly like me. As I dug through her blog archive it was easy to track how every aspect of her physical appearance was a distinct choice that had differed from my own—the slender, intentional sculpt of our thick eyebrows, the consistent application of a rosy gloss to our lips. We had begun with the same canvas, but where I remained mostly unedited, she had made a series of careful alterations that accumulated into a unique, recognizable style—one which made her fairly popular within the delicate ecosystem of our online sphere. As I clicked through her photos late into the night, the internet introduced me to the girl I could have been.

In those days the blogging platform felt like the center of something—not the world, not yet, but a bustling digital city which housed many small communities. Mine was a collective of teenage girls with an abundance of feelings who made up stories together and planned for the possibility that our hearts might one day be broken. (We each already knew the songs we’d listen to if this ever came to pass.)

My recent discovery of this community had imbued me with the conviction that I was missing something powerful and important anytime I looked away from the screen. Without a doubt, something was happening without me. And so, as my father slumped in his frayed armchair on the other side of the house, absorbing the expanding hours of the television news cycle, I submitted to the unrelenting pull of this online world as if relinquishing a part of myself.

I kept up with many blogs, but my doppelganger’s held an unnatural, obsessive fervor for me that never wavered. We were the same age, yet she seemed lightyears ahead of me in every conceivable way. While I was still trying to figure out how to talk to my own teenage classmates, she wrote about dalliances with a friend’s older brother or the casting directors she charmed at her acting auditions. It was a life that seemed invented purely for the entertainment of others, too perfect and plotted to be true.

The text posts were enlightening, but it was the pictures I truly craved. Every update left me scrutinizing my computer screen, for my doppelganger seemed to have cracked the mystical code of girlhood—one which remained maddeningly impenetrable to me. She wore lacy dresses and floral prints while I mostly stole shirts out of my father’s closet, oversized flannels that flattened and disguised my body, turning it into a mysterious landscape as opposed to anything with shape or substance. She posted close-ups of the elaborate make-up she did herself for bit parts in independent films while I struggled to apply mascara to my lashes without crying.

Back then femininity felt like a language I was doomed to be hopeless at learning. Sometimes I would gaze at an outfit that looked something like hers in a fast fashion store at the local mall, occasionally even sneak into the fitting room to let the unfamiliar textures brush against my skin. But every time I zipped myself into one of those dresses, I had the peculiar sensation that I was trying to step into a space that already had a person inside of it.

Her archives were eventually eaten up in rounds of digital obsolescence, as the internet’s endless evolution separated us all from iterations of our former selves. For years I lamented that I had not saved any of her pictures; her similarity to me felt more and more like something I had dreamed, concocted as a coping mechanism for my own failure to fit in.

I’d had my own account on the blogging platform, though I never made a single post. Following the site’s painful, prolonged demise, long after the community had scattered and divided among the host of flashy new options for digital connection, when nothing remained but a maze of broken hyperlinks and errors papered over images, I still remembered my icon. A single gray square on a page, an outlined avatar devoid of features. A question mark where a face should be.

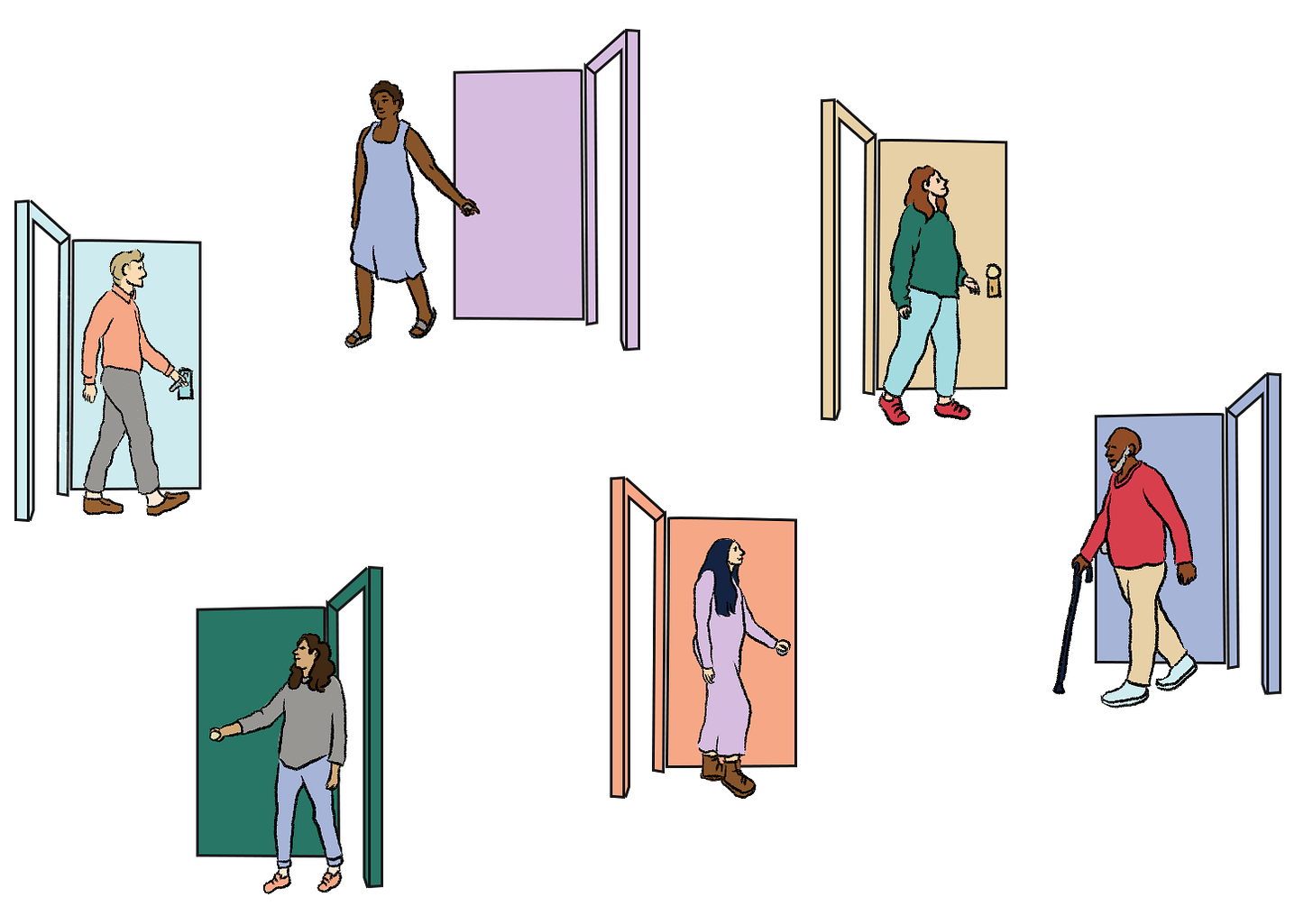

As time passed, I began to feel more like the internet had become a gigantic stadium with no partitions at all. Nothing separating us any longer. Everyone screaming at once. But back then the internet felt to me like an infinite series of small doors we were all walking in and out of, and once in a great while you might cross paths with the person who would change your life.

I kept up with many blogs, but my doppelganger’s held an unnatural, obsessive fervor for me that never wavered. We were the same age, yet she seemed lightyears ahead of me in every conceivable way.

Fifteen years went by and it was my first time at the renowned independent film festival. I had never before left my small town, choosing instead to remain as my father aged and eventually needed someone to care for him, the way he had for me—a role reversal that carried on for a few years before his death. He left me the house and his truck; in his absence, I became convinced that these were the only things still tethering me to the earth. Staying in the same place was the only antidote to the surreal unmooring sensation I experienced after his death, which was exceedingly acute that first year in particular. There were some mornings, after walking out the front door and closing it behind me, I felt gravity might release its hold on me for good and I might simply ascend into space, floating there in the ether, that much closer to the sun and stars.

What kept me going was my gig as a film critic for the local paper. Our town movie theater was a hundred-year-old cinema with a single screen whose owner relied on me when picking which new releases to show. After my father died I threw myself into this responsibility wholeheartedly, surrendering myself in total to every story I consumed. My recommendations were often independent films of the most depressing ilk, which was noted in the occasional emotionally exhausted letter to the editor—usually from a citizen with simple tastes who just wanted to know if the new action hero franchise sequel was any good. I didn’t know how to explain that crying about someone else’s pain was somehow more cathartic than crying about my own. I was tired of thinking about personal loss and wanted to drown myself entirely in a fictional reproduction, if only for the mere duration of a ninety-minute runtime.

I plodded on with my series about very good but decidedly miserable critically acclaimed indies, which the paper began publishing online after they belatedly acquiesced to digital expansion. I had not expected anybody outside of our little town to take notice of my work, but against all odds, one day, someone did. I had been invited to the film festival as part of a new campaign they were running to elevate perspectives from rural locales. It seemed the internet had one more door to open for me.

And here I was entering it, like a girl with an invitation to a ball—but still the same frumpy outfits.

I pulled my puffer coat tighter around my shoulders and slipped quietly into the theater, closing the door to the frigid air behind me. True to form, I had gorged myself on misery from the very first screening, attending premiere after premiere of films about death and absence and emptiness; this one was said to be a ghost story. I took a seat near the back as the lights went down, pulled out my notebook and pen with the little flashlight on its end—and that was when I saw myself.

My nose. My cheeks. My eyes. My lips. My hair, forehead, chin, ears. Everything that came together in the mirror to form my understanding of myself, blown up and projected on the screen.

It was me.

Another moment of frozen awe passed before my brain jolted back to regular speed and began to skitter forward with new understanding.

No—it was her, of course. My doppelganger.

It was as if the film had somehow soaked up her importance to me and was now reflecting it all back in a concentrated, magnified haunting. The psychological effect was so intense as to be physically nauseating. I clutched the armrests of my seat as she traipsed around the dimly lit Victorian house in an ethereal nightgown, calling another woman’s name. Tongues of flame flickered perpetually on the tips of the tall white candles surrounding her. The long train of her dress slid after her like a pale shadow, following her silently from room to room.

Two women who loved each other had once lived alone together in this creaky, ancient house—but which one of them was dead?

It was the kind of film I normally loved, a metaphor-heavy ghost story that took great ravenous bites out of grief, digesting sorrow into nightmare. But even as I felt the old hunger return, I could not shake the eerie feeling that I had, once again, come right up on the edge of some existential line. My doppelganger had only ever wanted to be an actress—her posts had told me that. But it was one thing to absorb these posts at a distance and another to be here, at the premiere. I realized with a dull spark of apprehension that she was likely in this very room.

Now that I was older and had recently experienced great loss, I felt overwhelmed by a sudden responsibility to maintain the remaining distance between us, before that line was crossed. She had no idea that I existed, and I should keep it that way. I was afraid to establish a bond between us that ran both ways. I resolved not to review the film.

Some might call my superstition unfounded. But I had seen the films and read the stories about the various collisions of identical people and the results were almost uniformly catastrophic.

And so, even in the face of the intoxicating force urging me to stay, I pulled myself from the chair and escaped before the film concluded, her pale face twisted like a screw in my mind’s eye.

For the remainder of the festival I was terrified of running into her. I stacked my days with screenings and otherwise attempted to hide away in my hotel room. Unfortunately, her film was quickly becoming a critical hit and we were both recognizable as a result. Attendees began to stop me in lobbies and even on the street, proclaiming their admiration for a performance I had not given in a movie I was not in. I did not bother to correct anyone in these situations, preferring instead to smile and hurry away before more attention could be drawn.

On my last night I was accosted on the sidewalk by a group of inebriated cinephiles. Her film had won an award the night before and they apparently wanted to celebrate by forcing her (me) to drink with them.

Inside the bar I eyed the amber liquid in my glass suspiciously while the cinephiles tried to engage me in their ongoing game of sequel-based horror trivia. A few questions later, one of them was violently ill in the nearest trash can, at which point the harried bartender asserted that they might better enjoy themselves in a place that was not his bar.

Relieved that an opportunity for exit had so quickly presented itself, I rose before my untouched drink and began to fumble with the uncooperative zipper of my puffer coat. A dreamy, lilting pop song began to play on the jukebox, sung by a familiar group whose name I could not for the life of me begin to recall. Lyrics I knew by heart about the strangeness of a certain kind of love. How the self can begin to disappear, if you’re not careful. The song had been on my future breakup playlist, many years prior.

I grabbed my tote bag and noticed the cinephiles had already gone, taking their drunken musings on practical effects with them. The scent of bleach cut sharply through the air; the much put-upon bartender was cleaning up after the sick one with a series of emphatic sighs. I turned to go.

But she was standing there, wearing my face, the door closing behind her.

The shape of her smile lingered briefly, though any previous joy had leached away and the stretch of her mouth was more a memory of happiness than any active expression of pleasure. I expected shock or fear, but as she returned my gaze there was nothing more than a sense of ah, there you are. As if she had been searching for me all this time.

The bartender’s huff of finality snapped us out of our mutual reverie. He slapped his knees and slowly rose back to his full height with the exhausted groan of a man in his early thirties who feels, spiritually, much older. His gaze drifted over to us and he seemed to awaken abruptly; he blinked several times.

“Hey, whoa. Are you two—”

“Sisters,” finished my doppelganger. She winked at me and loosened the tie on her black trench coat, revealing a delicate white evening dress beneath. I swallowed.

The bartender stood there staring for a beat longer, then clapped his hands and crossed the checkerboard floor.

“Always happy to facilitate a family reunion. Anything to drink?”

She pointed at the untouched beer still resting on the bar in front of me.

“I’ll take one of those.”

She slid into the seat on my right. It was somehow easy to consider her beautiful, though I had never thought that of myself. I was wearing a gray blazer that had belonged to my father over a thrift store t-shirt bearing the image of a cartoon dog. I still wore a lot of my dad’s old clothes. My hair was in a low ponytail. I looked down into my drink and saw my face; as the bartender placed a second drink on the counter, I got an odd chill from the idea that she was seeing the same thing in hers.

“Hello, sister,” she said, taking a sip. I understood we were playing out the charade for the bartender’s benefit. He looked relieved now that she had presented shared DNA as a reason for our similarity; his attention drifted as he moved toward a pile of shot glasses further down the bar.

For a moment it felt like we were on the cusp of a revelation. I wanted to tell her I had read her blog, years ago. That I had been aware of her existence all this time and I was so happy her dreams had come to fruition. I felt a stake in her success not even just because she looked like me, but because I had intimate knowledge of her desires—had perhaps at some point even internalized them as my own.

But I found that I could not speak, and so for a moment it was as if nothing had changed. An avatar with a question mark for a face and no posting history. I blushed and smiled awkwardly.

“Amazing,” she said softly, tracking the shifting expressions on a face that was so like her own. She took a long drink. “Where are you from?”

I told her.

She nodded, still searching for an explanation. “And your father?”

“Never left the state.”

“I see.” She looked down into her drink, reflecting what I also saw in mine, and seemed to accept this new facet of her reality.

“Have you considered acting? They could cast us in a movie. Or stunts.” She smiled at me, cocked an eyebrow. “Are you the daring type, sister?”

“I can barely ride a bike,” I laughed.

She clicked her tongue. “A pity.”

For a moment it felt like we were on the cusp of a revelation. I wanted to tell her I had read her blog, years ago. That I had been aware of her existence all this time and I was so happy her dreams had come to fruition.

With a jolt of surprise, I registered that a second song from my breakup playlist was now streaming out of the jukebox. Folksy guitar, a crooning duet, a promise broken. Perhaps it was all a dream, I thought deliriously. I had imagined this meeting so many times I was unconvinced it was actually happening.

“And what do you do?” she asked.

“I’m a critic.”

“Ah.” She smiled knowingly. “Did you see my movie?”

I nodded. Easier to fib than explain.

“We’re pleased with the response,” she said, though she continued to watch me closely, as if she didn’t quite believe me. But what reason did she have to doubt? Everyone at the festival had seen the film by now. I shifted on the barstool.

“Especially the ending,” she continued. “The twist.”

“Right.”

“It’s been interesting to hear people talk about it,” she said. “Now that it’s out in the world.” She cracked an odd smile. “Who do you think the villain is?”

Was it a test? Maybe she was honestly just curious. I strained to remember the two female characters, wishing I hadn’t left early. “Hard to say…”

“I admired the script for that reason. I suppose I’m biased toward my own character.” She said this with the loving caress of a mother speaking of her child. “But they both have their flaws, don’t they?”

“Right,” I said to my reflection. “Flaws.”

My song ended and another began—one I didn’t recognize. She threw her head back, closed her eyes. “Mmm, I love this one.” And then she looked at me. “Want to dance?”

Before I had the chance to respond, she was pulling me off the barstool, leading me out to a hollow in the midst of the tables and chairs. We had caught the bartender’s eye again; he was wiping the rim of a single glass in endless loops. There was an expression of simultaneous discomfort and interest on his face, as if he did not want to watch us and yet could not bring himself to drag his gaze away.

Fractured blue light fell across my doppelganger, illuminating our similarity in pieces. She began to sway in time to the music, glowing as she moved. She was a bit taller than me in heels. I followed her lead, mimicking her movements as I strained to catch the singer’s words. It was a sad song with a fast beat. Something about sacrifice. Something about loss.

“You know, they say it’s bad luck for us to have met,” said my doppelganger.

How did she do that to her hair, I wondered. A few strands had come loose from their silver clip, but like the rest of her ensemble it seemed intentional—a cultivated look that deconstructed her beauty. I wondered if the fact that she had done it meant that I could do it, too. As if she was paving the way for me, showing me that certain things were possible.

“Why?” I asked, even as I felt eerie echoes of my previous misgivings in her screening earlier that week. All the time I’d spent decidedly avoiding her, only for her to show up blocking the door I was trying to use. Either a sign or a coincidence. “What’s unlucky about it?”

“According to some stories, one of us might steal the other’s life.” She smiled, a devious little flicker in her eyes, and put her hands on my shoulders. “I wonder if that means one of us is the ‘original’ and the other is a ‘copy.’”

I flushed. Perhaps she was the revised version of me, all of my errors and the things I didn’t like about myself improved upon.

“I’ve had the feeling before,” she mused, “that I’m here by accident. Maybe that’s why my films have been well received. Because they were brought in from a universe where they would be considered derivative, but here they’re original, presented as something fresh and new.”

She shook her head, her gaze losing its far-off quality.

“And how do you feel,” she asked me then. “About your life?”

I looked at her and I could remember everything I wanted to change about myself. The things I liked about her denoted all that I hated in me. I loved her and despised her, this better version.

“I don’t feel like a failure,” I managed, “But I haven’t exactly succeeded either.”

For I was proud of certain things. That I had taken care of my father the way I did, providing relief and comfort in the last years of his life. And I did still occasionally experience a burst of satisfaction when I finished a review and knew that it was good.

But my father was just one man, and the newspaper’s readership few. More people had likely seen my doppelganger’s movie at this one festival than had read my reviews combined. My efforts mattered, but my impact felt microscopic. And I worried I had reached a plateau.

The song played on. Maybe this was the moment that something changed.

“You should believe in yourself,” my doppelganger murmured, and then she reached up and touched my face. “You are still allowed your dreams.”

Dreams? I blinked at her. Dreams were a luxury. Ideas of a future that had always seemed beyond my reach. Over time I had blotted out any other possibilities, accepted this as the sole version of myself I was capable of being. The limits became a part of my life; I had embraced them. Internalized the idea that I would never be more than this: my small town, my sad movies.

And here was this glimmering avatar of possibility before me, suggesting another path.

Her song finally ended; she stepped back.

“We should meet again, I think. But you have to promise you won’t steal my life.” She gave me a stern look, yet there was something playful about it. I couldn’t tell if she was being serious or not. If I had been making the expression on her face—the eyebrow cocked, corner of the left lip curled—I would be cracking a joke.

But, I reminded myself, we were two different people. Even if she was my sister, or my doppelganger, or a self from another universe. I would still leave the bar as me, and she would still be her.

In theory, anyway.

Abruptly she walked back to her seat at the bar, began to gather her things. I was reeling, standing in the middle of the floor alone. She came back wearing her coat, extended her hand to shake mine.

“You should write about my film,” she said, and I understood now that I would. That this was an invitation to change something about the present.

She left, and I watched the door swing to a close behind her. Through the window I could see her dancing recklessly across the street, laughing as she went, narrowly missed by a late-night driver, her body and heart buoyed by an effortless joy I’d always wanted.

And that was when I realized I hadn’t made the promise she’d requested.

I heard a clink behind me; the bartender finally set his cup down. The cleanest cup in the world.

“She wasn’t your sister, was she?”

In the years that followed, we kept meeting. It felt like a kind of magic, and if we stopped, the spell would be broken. We met in the same bar at the same festival in the same cold weather with the same bartender watching us behind the counter. Every time, her voice in my head: You are still allowed your dreams.

For a little while, we were both carving out success for ourselves in our respective fields. She performed in indie films that did well in the arthouse circuit and even won awards. I held positions at several different publications before finally scoring a columnist gig at a prominent newspaper. Pictures from her Vegas wedding were sold and published in a magazine I saw on stands in the grocery store. I sold my father’s house and bought an apartment in the city, where I adopted a pug named Cocteau, whose wrinkled squishy face soothed the pulse of grief over time. I occasionally reviewed a comedy. I began to allow myself small measures of joy.

What impulse kept us coming back together? I know how it felt for me—a strange curiosity. Like tonguing a sore. Like pressing a bruise. Like brushing up against some impossible beauty that shot a pang of longing through you, seeing and knowing and briefly touching something you thought you could never have.

At first, the reunions felt like her way of checking up on me. To confirm the velocity of her career ascent consistently exceeded mine. That the permission she’d given me hadn’t allowed me to surpass her in any way. Our connection wasn’t a relationship so much as a fleeting alignment. At some point there had been a fracture. Perhaps it was a result of our first collision, the cracks spreading outward. And so things began to change.

Her fairy tale marriage ended in a very public divorce, the kind that shows up on the first page of browser results when you search somebody’s name. She publicly reframed the breakup as a feminist liberation. But there was no way to rebrand the DUI that came later. There were reports that she was challenging to work with; her public exploits made her difficult to insure, so her roles dried up. Her addiction was far more extensively reported than any of her career success had been. The fall was meteoric.

As her life crumbled, mine continued to improve. It was as if we had briefly met in the middle, and from that intersection of our lives mine had shot upward, climbing a steady hill, and hers had spiraled down, and now we were both about to see how it would end.

Every time I saw news of her online or in the magazines, I remembered how bare she’d made herself in those early internet days. How nakedly she had displayed her dreams. How frightening and inspiring it had been to see her share her desires for the future out loud.

In strange, quiet moments I felt like a villain plucked from one of the many films I watched, but I always quickly directed myself back to a place of calm logic—surely nothing in my life had any real impact on hers. We’d been drawn together by coincidence, and nothing more. Our lives were set on certain courses from the beginning, by money and personality and opportunity and our ways of being in the world. There was no way out of those bubbles. Our overlap had been a fluke that changed nothing.

I thought.

But sometimes, I looked in the mirror and wondered.

I searched once more for that early self in the internet’s vast archives. The dreams she’d had, which I’d known so intimately they felt like my own. But there was no record of them anywhere. That other girl was gone.

Every time I saw news of her online or in the magazines, I remembered how bare she’d made herself in those early internet days. How frightening and inspiring it had been to see her share her desires for the future out loud.

The last time we were supposed to meet, she never showed. The bartender watched me as the jukebox cycled, finally pronouncing, “I don’t think she’s coming, love,” in a way that I understood to be final and true. I resigned myself to a new kind of solitude and left the bar alone.

But I found her across the street only a few blocks away.

She was standing on the sidewalk in a ratty gray sweater, her eyes revolving in the sockets of her skeletal face. She was gaunt, compressed, diminished. As if I’d siphoned something vital from her.

I could see all the things I’d hated about my fourteen-year-old self there—the fear, the desperation, the yearning. The transparent desire for this day to be different from all the others. Somehow I had moved further along her timeline of success, and she had funneled back to my early stages of failure.

I stood there on the other side of the street. I remembered the bar, our dance, her hand on my cheek. You are still allowed your dreams. Had our meeting created some rift in the continuum of our lives, redirecting both of us onto new tracks, like railcars shifting?

All these intervening years I couldn’t shake the feeling that I had stolen something from her, something that wasn’t supposed to be mine. As if joy had been her birthright, as if success was something I borrowed and never gave back. And I the parasite, the alien, the evil twin.

For on that first night, when the cinephiles insisted I was her, there had been a moment that I perversely reveled in. The undeniable euphoria of being someone else, freed from the burden of my own history.

I hovered at the end of the crosswalk for an agonizing clutch of minutes, and then I crossed the street. As I approached her pallid face and open palms, for a moment I thought I could give her everything. I thought I could undo the strange magic that had passed between us. Reset the scale. Right the wrong. I gripped my wallet inside of my purse, which held the various plastic cards that all bore my name, and some the face we shared. None of it had ever felt earned, felt owned, felt mine.

Do we ever reach a point where it becomes too late to change? Where the decisions you make reset the course one more time and that’s it, that’s the end—this is your life, this is who you are?

My feet were sweating in their Chelsea boots. I kept walking.

STORY:

Abigail Oswald writes about art, fame, and connection. Her work has appeared in places like Best Microfiction, Catapult, Bright Wall/Dark Room, DIAGRAM, Memoir Mixtapes, The Rumpus, and a memory vending machine. She's also the author of Microfascination, a newsletter on pop culture rabbit holes. Abigail holds an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and can be found at the movie theater in at least one parallel universe at any given time. More online at abigailwashere.com.

*

ART:

Aubrey Hirsch is a writer and comics artist. You can find her work in the Washington Post, Vox, TIME, and elsewhere. You can follow her on instagram: @aubreyhirsch.

Next Tuesday, we’ll feature a bonus interview with Abby about this story!

Dude. Holy shit. Love a good doppelganger or twin story and this one's magic. Just thrumming along so many throughlines. I was immersed. The haunted light of seeing who you could/should be on the early internet is dope. The voice, the vibe. The art too, especially that piece up top. Nice work everyone.

Spectacular story. A good doppelgänger story hints at fantasy (I’m thinking of Poe’s “William Wilson”) but this one immerses us in the mundane, with results perhaps even more horrifying! Well done!