The Good News Caboose by Adam Petty

"Inside, the Good News of the Gospel was shared, in the form of grainy evangelical message films from the 80s, a relic of shoestring youth outreach efforts..."

As an incredible sucker for well-told stories of growing up and coming of age, the beginning of this story got its hooks in me pretty immediately. An awkward sixteen-year-old youth group kid in the 90s becomes friends with a more assertive, defiant, swearing, Nine Inch Nails t-shirt-wearing kid, and they go together to their local county fair, the “highlight of the social calendar in our small town”? I could, quite possibly, not be more in!

And then, halfway through, it takes a turn a different kind of story. Something a little more mysterious. I don’t want to give anything more away, but I fell for this story pretty hard upon reading it as a submission and have been excited to get to share it for a while. I hope many of you fall for it as hard as I did!

—Aaron Burch

1

It was the summer of 1998 and I was, as they say, sixteen. Unruly hormones squared off in the volatile streets of my body, even though, outwardly, I was an unremarkable specimen of masculine adolescence. I wore thick, corrective lenses. My teeth were heavily orthodontured and I never smiled. I dressed in shapeless clothing from thrift stores, the hand-me-downs of nonexistent older siblings. The acne scarring my face was the only evidence of the turmoil roiling inside me. This tension—volatile interior held in check by a bland façade with surprising ease—expressed itself in my life as well. Sullen as I was, given to brooding over grim topics, I remained, as the adults in my life put it, ‘a good kid.’ I went to school. I got good grades. I didn’t get in trouble. We attended an evangelical congregation where congregants raised their hands and cried during services. I did neither, my blandness unshakeable.

I fell under the sway of an assertive boy at my church’s youth group. His name was Trevor and he was everything I was not. He slouched in his chair during Bible study. He wore a Nine Inch Nails shirt. Occasionally, when feeling especially defiant, he swore.

My parents disapproved of my choice in friends, even though, strictly speaking, I didn’t choose to befriend Trevor. He befriended me, the alpha sniffing out a beta, corralling me to do his bidding. But I was otherwise friendless, and my parents’ disapproval was outweighed by their pity.

During the summer in question, I followed Trevor to the county fair, the highlight of the social calendar in our small town. One might think, with the pleasures offered by video games, rap music and internet chatrooms, that the youth of our town would have spurned the old-fashioned charms of the fair. But we clung to it desperately, claiming this one little ritual as our own. Confronted with the shiny baubles of the New on a daily, if not hourly, basis, any tradition stretching back more than one generation possessed the stately solidity of the Parthenon.

Trevor played, and lost, games of chance that were obviously rigged. He ate elephant ears. He tried out one-liners on girls, to no avail. His failures did nothing to diminish my high regard of him. If anything, I was even more impressed by his persistence. He may have swung and missed, but at least he had the courage to step up to the plate.

Off the midway stood the Good News Caboose, a trailer painted red, the shade familiar from model train sets. Inside, the Good News of the Gospel was shared, in the form of grainy evangelical message films from the 80s, a relic of shoestring youth outreach efforts, before evangelicalism was wholly absorbed by megachurch slickness.

“Want to go see?” Trevor asked, which confused me. Trevor regarded church with disdain, even hostility. That was why my parents thought him a bad influence, and also why I idolized him. Why would he want to see a Jesus movie?

Trevor entered the Good News Caboose without saying another word, and I followed. I took a seat next to him just as the next showing began.

Presiding over the Good News Caboose was a thin man, short-sleeve button down shirt tucked into Wrangler jeans. He thanked us boys and girls for coming. He had something very special to show us. He fed a VHS tape into a VCR, then turned off the lights. The television crackled to life, bands of static cohering into images.

The film was a morality fable of the sort designed to guilt young people into asking Jesus into their heart. A teenage boy skips school, talks back to his parents, and generally makes a nuisance of himself. He says he doesn’t need God. He can do everything for himself.

I had come here the year before, but I had no memory of the film I’d watched. Was this film the same as last year, or a new one? Not new, exactly—the grainy film stock, shoddily transferred to VHS, evoked that precarious stretch from the late 70s to the mid-80s with pinpoint accuracy—but new to the Good News Caboose? I couldn’t say.

In the dark, I glanced at Trevor. His eyes stayed on the screen. Did he see the resemblance between himself and the film’s protagonist? Was that what he wanted to show me?

At school, a pretty girl asks the teenage boy if he knows Jesus. He sneers, and it’s almost convincing. He goes to a party and drinks beer. He drives home late at night, and on account of the beer, he crashes his car, dying instantly. Unsaved, his soul goes to hell. The pretty girl says so, speaking quietly to friends at the teenage boy’s funeral.

The film unnerved me, but not for the expected reason. I had asked Jesus into my heart when I was eight, and though often I worried I hadn’t really meant it, that was not what worried me now.

In the film, when the teenage boy crashes his car into a tree, the shot lingers, panning out, displaying the full length of the car. And as it pans out, another figure appears onscreen, standing next to the car. A younger boy, eight or nine years old, wearing a red shirt. He does not appear anywhere else in the film. The shot holds for a moment, then cuts to the funeral.

I couldn’t say why, but the sight of the boy in the red shirt, just standing there, frightened me more than the fear of eternal damnation.

The film ended, and the thin man asked us a question. “That boy made a big mistake. Does anyone know what it is?”

Trevor spoke up. He’d been waiting for this moment. “He should have called a taxi!” he said, pleased with his own joke.

The thin man gave a thin smile. He was used to such pranksters.

“He didn’t accept Jesus into his heart, and then he died. Do you know what happens to him then?” Silence from the Caboose. “He goes to hell. That’s what happens. I know you’re young people and you think you’ll live forever, but let me tell you, no one knows the hour or the day. Are you ready? Do you know if you’re really saved?”

“He sure wasn’t! Don’t drink and drive!” said Trevor. No one laughed.

“Who was that boy?” I said.

For the first time, the thin man looked puzzled.

“The boy in the red shirt, standing next to the car. Who was he?”

“He sure made a big mistake, didn’t he?” said the thin man.

“No, not the boy who died. The other boy next to the car. Who was he?”

The thin man ignored my question. He proceeded with his altar call, asking if anyone wanted to give their life to Jesus. When there were no takers, he did not become frustrated.

I followed Trevor out of the Good News Caboose. Still excited from telling off the thin man, he bought me a Sno-Cone.

“Did you believe him? Pathetic,” he said.

“Who was that boy in the red shirt?” I asked.

“Lay off it.”

“You saw him, didn’t you?”

“I said lay off it! It doesn’t matter, it’s just a scam.”

The rest of the evening, I dragged my feet. Trevor became annoyed that I wasn’t keeping up with him, and eventually abandoned me. I rode my bike home alone.

The next day, I rode to the supermarket. I had a summer job there as a bagboy. During a lull in the front end, I was dispatched to the stock room. The latest bread shipment needed to get stocked. I wheeled the bread past the aisles, which were mostly empty this time of day. But in the detergent aisle, immobile, stood a lone customer.

It was the boy in the red shirt, from the film. I was sure of it.

I set the bread down, losing sight of the boy as I did so. I ran back to the detergent aisle, but there was no sign of the boy. I looked down the other aisles, frantic. Still no sign of him.

I ran to the front end and told my manager there was a missing boy on the floor, a boy in a red shirt. The manager leapt into action. He put out a call on the intercom, asking the customers if anyone was looking for their son, a boy in a red shirt. Panic electrified the store.

When no sign of a boy in a red shirt was found, the manager chewed me out.

“If you ever cry wolf like that again, you’re fired!”

I couldn’t even look him in the eye.

*

At home, I called Trevor. My mother frowned but let me have the kitchen to myself.

“I think I saw him at the store.”

“Who?” said Trevor.

“The boy in the red shirt, from the film.”

“You’re still on about that? It’s all a scam. They put up crosses at the front of church, but they should put up dollar signs. At least that would be honest.”

“Didn’t you see him?”

“Forget it, man. Forget all of it.”

But I didn’t. That evening, I went back to the fair on my own. I went to the Good News Caboose and sat through the film. But when the scene came, where the teenage boy crashes his car into the tree, there was no sign of the boy in the red shirt.

The lights came on and the thin man asked if we knew what the message was.

“Where is he?” I said. “Where is the boy in the red shirt?”

“You again?” said the thin man. “You came here for a reason. Have you accepted Jesus into your heart?”

“I’m not here for Jesus! I’m looking for that boy!”

The thin man was taken aback. Without even trying, I had committed a far greater sacrilege than Trevor.

“I want to help you, but I don’t know if I can,” he said. “You have the devil in you. I feel him. I’ll pray him out if you let me. Let me do that for you.”

The others in the Caboose were riveted. This was far more thrilling than the film.

“Tell me what happened to him,” I said. “Tell me what you did with him.”

“Get out of him, devil! Leave this boy in peace.”

The thin man stepped forward. I lunged for the television. He must have switched out the tape. I was going to prove it.

But the thin man must have thought I was trying to destroy the film, the devil in me fearful of its righteous power, and he dove forward. I collided with him and fell to the ground. The thin man remained upright, surprisingly sturdy.

“Out, devil!”

I ran out of the Good News Caboose, stumbling through the fair. The thin man stood at the door of the Caboose, shouting.

I got on my bike and pedaled furiously. I didn’t know where I was going. I didn’t recognize the streets I was weaving through. But I did recognize the boy.

There, in the middle of the street. The boy in the red shirt. The boy from the film. Staring me down. Not saying a word.

“What do you want with me?” I said.

The boy remained still. I placed my feet on the pedals, preparing to head for him, to knock him over if necessary. I started pedaling, and the boy remained in place. I pedaled faster, and still he remained in place, and just before I reached him, there came, from behind him, headlights.

I skidded off to the side and fell into a ditch. I lifted myself from the ground and hobbled over to the road. There was no sign of the boy. The headlights, however, were still on. They belonged to a car. A car that, in its swerving, had crashed into a tree.

The windshield was shattered and the airbag had deployed. There was a bright red smear of blood on the white canvas. Behind the wheel, him.

Trevor.

2

It was the spring of 2005 and I was, as they say, unemployed. I spent my days in the bedroom. When I shuffled to the kitchen to nuke a breakfast burrito in the microwave, my mother looked away. She couldn’t bear to behold her go-nowhere son, no college, no prospects, no life. I obliged her, saying nothing. I took my breakfast burrito back to my room and ate alone. I sat, as always, in front of my computer.

My mother’s estimation of me was not entirely correct. Yes, I lacked ambition. I lacked direction. My grades had nose-dived junior year and never recovered. I couldn’t hold down a service job for more than a few months at a time. I was a poster child for the aimless post-adolescent male.

But I did have one thing in my life, one vessel for my meager energies. I had an obsession.

I was searching for the film. The film the Good News Caboose had played seven years before. I was searching for the boy in the red shirt.

When Trevor died, my parents tried their best to contain their relief. Yes, my friend had died. Yes, it was tragic. But that was what they wanted, to have Trevor’s poor influence removed from their son’s life. And they sure got it. But it backfired.

Had my youthful friendship with Trevor been allowed to run its course, I would have outgrown him in a few months’ time. Over the intervening years, I had come to see Trevor for what he was. A bully, a low-rent alpha lording over me, his obedient beta. He was annoying. He was arrogant, and lacked the intelligence to back up such a quarrelsome trait. He was, ultimately, dull. But he had died at the peak of my involvement with him. Taken from me so suddenly, I became obsessed with him and the bizarre circumstances of his death.

Consumed as I was, I had met with little success. In the summer of ’98, the day after Trevor had been killed, I returned to the county fair. I went to the Good News Caboose to wag my finger in the thin man’s face, to accuse him of siccing the boy in the red shirt on Trevor. But the Caboose was gone. No one knew where it went. The carnies were magnificently unhelpful, shooing me off with switchblades.

I looked everywhere I could think of. I begged my mother to drive me to the fair the next county over, to see if the Good News Caboose was there. It wasn’t. My mother performed her best attempt at sympathy, saying it was hard to say goodbye, but it wasn’t my fault. Trevor was in a better place.

“You’re right,” I said. “Hell is better than here.”

Our relationship wasn’t the same after that. My mother forever bracing herself for the next awful thing I might say.

Months passed, then years. I looked for the Good News Caboose however I could. I got my driver’s license and drove across three states, stopping at every small town fair I came across. No sign. I asked churches and ministry organizations if they’d heard of the Good News Caboose. None had. I learned how to navigate the burgeoning internet, acquiring a computer for Christmas and trawling the chat rooms of media archivists. Nothing.

Then, in the spring of 2005, my salvation arrived in the form of a portmanteau: YouTube.

YouTube was it. Exactly what I needed. Video after video after video, all of them loading instantaneously. Gone were the days of waiting hours for minutes of grainy footage to buffer over jerry-rigged, chewing gum-spackled dialup connections. I clicked and watched and clicked and watched, whole worlds of knowledge opening themselves to me.

I did not find the Good News Caboose film, but I did discover countless other artifacts of evangelical kitsch. Poorly-framed videos of adults in shoddy costumes acting out parables. Flannel graph stop-motion animation clips that were surprisingly artful, some anonymous craftsman finding expression for their talent in the basement below the community room. Sermons uploaded from camcorders, time-stamped in the corner with that distinctively blocky VHS font. The comments below the videos were filled with the remembrances of others like myself, devoted, for reasons they couldn’t articulate, to the digital ephemera of their youth group years.

I didn’t know anyone else remembered this. I thought it was lost forever. But it’s here, all of it.

Almost all of it.

One user, screen name psalty316, had uploaded dozens of videos, including a series of message films. Cheaply-produced moral treatises, filmed in the backyards of AV club enthusiasts and screened during church outreach nights. The same type of film as the one shown at the Good News Caboose. So far, psalty316 hadn’t uploaded any clips from that film. But if anyone would find it, he would be the one.

I chewed my breakfast burrito. I checked my email.

There was a message from psalty316. He used the screen name for his email address, obscuring his identity. I did the same. I posted under a dozen different aliases on dozens of different forums, my identity splintering fractally, my true name and face left behind.

Found something, wrote psalty316.

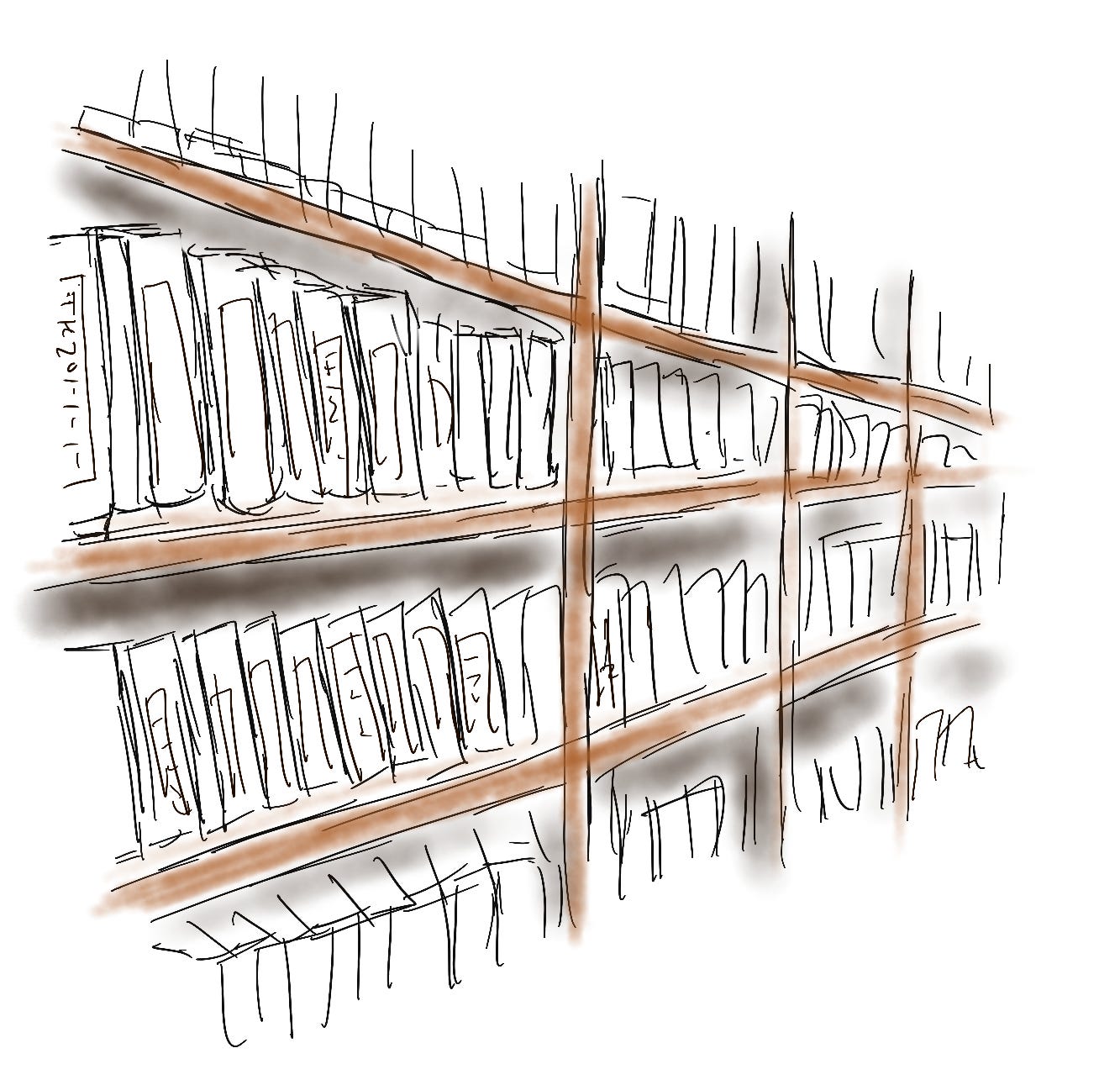

Attached to the message was a photograph. The spines of countless VHS tapes carefully shelved in a bookcase. A few of the titles were professionally printed; most were written in sharpie, in precise, neat handwriting. The titles indicated they were message films. Most of them I’d never heard of. A treasure trove of forgotten material.

But there was a problem. I didn’t remember the name of the film from the Good News Caboose. I’d tried to recall it. I’d asked other friends who went to the fair if they remembered it. None could. I remembered the teenage boy, the pretty girl, the car crash, and of course, the boy in the red shirt. But not the title. My memory couldn’t grasp it.

I opened a chat window and messaged psalty316.

It’s in there, I typed. I felt it. Felt its presence, somewhere on the shelves. The same feeling I’d felt seven years ago.

I know right, typed psalty316.

I have to see them.

There’s the problem, I didn’t take the pic. Someone sent it to me. I can’t get my hands on the tapes.

Does he want money?

The guy says the owner of the tapes doesn’t want to upload them. Says the internet is the devil’s playground.

I mean it is obviously. Look tell me where they are and I’ll talk to the guy myself.

You think he’ll trust a stranger?

I’m not a stranger, I typed. I’m a brother in Christ.

Thus began an exchange where I attempted to learn the physical address of the owner of the tapes, with psalty316 acting as an intermediary. The process took weeks, as my messages were conveyed to the one I thought of as the Connection, who passed them on to the one I thought of as the Owner. Eventually, I was given a date and an address. June 6, 10am, at a Perkins restaurant outside Dayton, Ohio. Was I to meet the Connection there? The Owner? I didn’t know.

Dayton was a six-hour drive away. I borrowed my mother’s car and asked her for money to cover a hotel room. I told her I had a lead on a job out of state, far away from home. She was all too happy to offer me assistance.

I drove down on June 5. I spent the night in a hotel, watching cable.

The next morning, I arrived at the Perkins an hour early. I ordered pancakes and coffee. At 9:45, a young man arrived. A strange spark passed between us. The Connection.

He looked familiar in a way I couldn’t place. He too was raised in evangelical circles, at once fearful of and drawn to the world beyond the walls of the church. The look on his face was one of wide-eyed suspicion. A look my own face shared.

“You’re here about the Good News Caboose?” he asked.

“You’ve heard of it?” I said. I was always the one who brought up the Caboose. The Connection mentioning it first was a good sign.

“There were several of them, traveling around. We supplied them with the films.”

“We?”

“Me and my uncle,” he said. The Owner. The Connection was his nephew. “We had dozens of films on VHS. But when DVDs came along, he didn’t keep up with the business. I tried to convince him this was an opportunity to reach more people. Cut out the Cabooses and sell the films via mail order to church groups. Build our own market. But my uncle wouldn’t budge. The films have to be shown in the Caboose, he said.”

“Why?”

“He’s stubborn like that,” the Connection said, not quite answering my question.

I told him about the film, the boy in the red shirt. The Connection didn’t answer my question. Although, now that I think of it, I didn’t ask him one.

The Connection asked a question of his own. “Do you want to see the films?”

I wanted nothing else.

*

I followed the Connection to his house. I sat in the living room as he went to get his uncle. Every surface was covered with trinkets: figurines, hymnals, blue ribbons. The walls were covered with embroidered samples of Bible verses.

The Connection returned, his uncle beside him. As they entered, a pair of realizations swept over me.

The uncle—the Owner—was the thin man. From the Good News Caboose. He was noticeably older, having developed a stoop to his walk over the intervening years. But it was him, unmistakably.

I looked at the Connection, the thin man’s nephew, in the light of this realization. It took longer to see the resemblance, but I saw it. He was the boy in the red shirt, from the film. When the film had been made, the boy looked nine or ten. Now he was in his mid-20s, same as me. But I still saw it. I felt it. The feeling I’d felt in the Good News Caboose.

The thin man and the boy in the red shirt, here before me. I was in their house. If they recognized me, they gave no indication.

Uncertain what game was being played, I kept my realizations to myself. I displayed my best poker face, even though the only poker I played was online.

“He’s looking for a film,” said the nephew. The boy in the red shirt, all grown up. In the film, as a boy, his presence was unnerving. But now he was deferential, insubstantial.

“We have lots of those!” said the uncle. It was the voice of the thin man. “Which one?”

“I don’t remember the name of the film. But I do remember one scene.”

“It stuck with you, huh?” said the thin man.

A taunt? A genuine question? I couldn’t tell. I’d lost all sense of discernment.

“Yes,” I said. I told them about the car crash, the boy in the red shirt.

The nephew’s expression didn’t change. His blankness so convincing that I questioned my realization. Maybe it wasn’t him? Maybe I was wrong?

“You saw the film in a Caboose?” said the thin man.

“Yes, in the summer of 1998.” I told him the name of my hometown. “I’ve been looking for it ever since.”

“The message touched you.”

“I saw the boy,” I said, frustrated he didn’t understand. “I was riding my bike, and I saw him standing in the street. I swerved, and then Trevor came out of nowhere, and he crashed into a tree. He died. Just like in the movie.”

“The message is meant to touch you. If it doesn’t, there’s no point.”

Had he even heard what I said? Was he deliberately speaking past me, same as he refused to acknowledge who I was and where he’d seen me?

“You’ve come to hear the message again,” he said.

“Yes, that’s it,” I said, though I never would have put it that way. I came here following my obsession, to find out what had happened to Trevor, how and why the boy in the red shirt used me to kill him. But in that moment, the way the thin man put it sounded right.

He shuffled out of the room. The nephew glanced at me. I followed the two of them, down to the basement. The thin man turned on a light.

There they stood: the videos. Shelf after shelf of them. The photo psalty316 sent me had shown only a fraction of the whole. There were hundreds of videocassettes. Enough for a whole fleet of Cabooses. The thin man let me take it all in.

“Each message is meant for someone,” he said.

He raised his hand, fingers extended, and waved it before the shelves. A spokesmodel on a game show, displaying the fabulous prizes I just might win. His hand stopped before one videocassette. Breath caught in my throat. If I exhaled, and took another breath, what would happen next? If this was the moment I had been waiting for, what would come after it?

He notched the videocassette from the shelf with his index finger. It slid into his waiting hand. He placed it in my waiting palms. I tried reading the label, but I couldn’t. Not because it was illegible. The handwriting was precise and without error. I simply couldn’t read what it said. My mind could not process the written word.

“Do you have a VCR?” I said.

“I have something better,” said the thin man.

We went back upstairs. Through a side door in the kitchen, we entered the garage. No car stood there. Instead, there was the Good News Caboose.

The thin man led me inside. The interior was just as I’d remembered it, as if it had been reconstructed from my own memories.

I sat in a chair, the same spot as when I’d sat next to Trevor. The thin man gave the videocassette to his nephew, who slotted it into the VCR. The television crackled to life, bands of static dancing across the scene, cohering into an image.

It was not the film I had watched seven years ago. It was, instead, a reenactment.

I saw myself on the screen. Myself at sixteen. Riding my bike down a residential street on a hot summer night. The boy in the red shirt appearing in front of me. The headlights appearing behind him. The car swerving out of the way. Crashing into the tree. The burst of blood on the airbag.

Trevor, dead.

Myself, approaching him.

Myself, turning away from Trevor, looking behind. Looking right into the camera.

The film ended. Crackled back into static.

“That wasn’t it,” I said to the thin man.

He was smiling at me. He held a camcorder.

“That wasn’t it!” I said again.

Why was I saying that? Didn’t I have more pressing questions? Didn’t I want to know how I had come to appear in the film?

“You still have the devil in you,” said the thin man. “You’ve carried it all this time. But I know how to get it out of you. I’m only sorry it took me so long.”

“What did you do to Trevor?”

The nephew had me stand. The thin man gave me the camcorder.

“Make sure you stay with it,” said the thin man.

The nephew opened the door of the Good News Caboose. I stepped through it, but I did not step back into the garage.

I stepped onto a residential street on a hot summer night.

As with the title written on the videocassette, my mind could not process it. But some instinctual part of me knew to raise the camcorder to my eye. I lodged my eye in the eyepiece and turned it on.

I see myself, myself at sixteen, riding my bike. I film myself riding past me. I film the boy in the red shirt standing in the road. I film the headlights. I film the car crash. I film Trevor’s lifeless body on the airbag.

I film myself looking into the camera. I film myself seeing myself.

I pan over and film the boy in the red shirt, now standing beside the car. He is holding out his hand. I take it. He leads me away. I film him leading me away.

Then I stop filming.

STORY:

Adam Fleming Petty is the author of the novella Followers. His work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Paris Review Daily, The Atlantic, Vulture, and other venues. He lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Find him online at adamflemingpetty.wordpress.com

.

*

ART:

Nina Semczuk’s writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Review, Sinking City Literary Journal, Coal Hill Review, and elsewhere. Her art, pottery, and comics can be found online and around the Hudson Valley.

Next Tuesday, we’ll feature a bonus interview with Adam about this story!

The thin man, the boy in the red shirt, the swerve. Love this.

VHS tapes, YouTube quests, mysterious online connections—I loved this!!