“The Free Throw Shooter” by Peter Witte

He told Tim about how this man arrived to the court and just started shooting free throws. “He hasn’t missed yet,” John said, “going on ten minutes now. He’s made over forty in a row.” Whir-clunk.

I’ve been thinking a lot this last week how one of the things I so love about reading is its unique mix of solitude and community or fellowship. When I am truly sucked into the world of a story or a novel, it can feel like an act of meditation or prayer, just me and what I’m reading, everything else turned down or even off. But, too, there is this connection. An array of connections! With the characters and the world of the story, but also with the author, with the people in my life the piece is reminding me of, with people in general for the way good art just makes me feel more alive, more a part of the world, more human. And then, too, many of my friends are readers and writers and I love talking about stories with them. I love recommending reads because I love championing and trying to promote art, and also because someone reading something on your encouragement, or you on theirs, feels like an exciting and beautiful kind of conversation and point of connection.

I was thinking about all that unrelated to today’s story, but now I’m thinking of it in relation, too. One of the joys of editing journals is the authors you get to know and work with, sometimes over and over, and I’ve gotten to publish and work with Pete a number of times over the years, across genres of prose and comics and providing art for stories from others. Digging through the archives some, it turns out the first time I published something by Pete was not only over a decade ago now (from 2013!) but was also, per his bio on that piece, “his first fiction publication”! (Of course, one of the other truisms of editing journals means that digging through those archives and the Submittable backend proves out that I’ve sent Pete a bunch of rejections over the years, too. Which isn’t really here nor there as far as all this goes, but always feels like a welcome reminder for the subjectivity of art and all that.)

And so there is that aspect of connection, but also, I’m now realizing, the story itself captures this wonderful overlapping of solitude and connection. There is the free throw shooter, alone in his world of shooting. Not unlike my description of reading as act of meditation or prayer. But then there is also everyone watching. This community of watchers, bearing witness, sharing this moment together.

It’s a really amazing story and one I hope many of you fall as in love with as I have.

—Aaron Burch

“The Free Throw Shooter”

It was another boring summer day in Normal, Illinois, when, at half past nine in the morning, a man, dressed in a white V-neck cotton shirt, black mesh shorts, white ankle socks, and black Nike high-top shoes, entered the schoolyard. He held a basketball on his hip, a jug of water in his hand, and a bag over his right shoulder. At the school’s basketball court, the man set down his things along the baseline, then looked at his watch.He strode across the blacktop and stepped up to the free throw line, used his shirt to wipe the sweat from his brow. He closed his eyes, tilted his head to the sky, and paused, as if concentrating or, perhaps, saying a little prayer.

After a few moments, the man lowered his head, opened his eyes and fixed them on the hoop, then dribbled once, twice, three times. He tossed the ball up, spinning it in the air inches from his hands. It rotated several times before returning to him, landing softly in his fingertips. He bent at the knees, then shot the ball swiftly: he lifted up and raised his arms high in the air, flicked his wrists, and his fingers released their grip. The ball arced through the air, toward the rim. The man’s left arm slowly came down. His right arm stayed in the air, seconds longer, with his wrist bent and fingers splayed and pointing to the basket.

Whir-clunk: the ball swished through the hoop and rattled the metal chain net.

The ball bounced on the blacktop till the man collected it, and again placed it on his hip as he walked back to the line. Again his eyes fixed on the hoop, he dribbled three times, then spun the ball in the air, caught, and shot it.

Again: whir-clunk.

And the man continued.

*

Nearby, John Fanning sat straddling his bicycle, tiptoes on the ground. He had been watching the man. John had come to the school’s basketball court to shoot hoops with his friend, Tim Dailey. Throughout the summer John and Tim had been regularly meeting at the basketball court located outside of Oakdale Elementary School where they had just finished the sixth grade. But Tim had not yet arrived. So, as he waited, John watched the mysterious man shoot free throws.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

Was that five in a row? Or six? John had lost count.

Whir-clunk.

He set the bicycle down and walked closer to the court, nearer to the mysterious man yet still at a safe distance, and he found a shaded section of the school’s wall to lean against.

Whir-clunk.

John started counting again.

*

Shortly, Tim arrived on foot, entering the schoolyard from the rear gate. He came dribbling a basketball and hollering at John from afar. John ran over to Tim and quieted him. He told Tim about how this man arrived to the court and just started shooting free throws.

“He hasn’t missed yet,” John said, “going on ten minutes now. He’s made over forty in a row.”

Whir-clunk.

“Wow,” Tim said. “Cool.” He walked over to get a closer look. Maybe, Tim thought, he could help with the rebounding. He stood near the baseline, not far from the hoop where the man was shooting.

Whir-clunk.

After the ball fell through the net, Tim went to grab the ball. But the man held up his hand, as if to say, “Stop.”

Tim backed away and joined John who was now again next to the wall seated on the blacktop.

And the man continued.

Dribble dribble dribble. Again, the ball spun in the air. Again, it landed in the man’s fingertips. He bent at the knees, then lifted up. He raised his arms high. Flicked his wrists. And his fingers released the ball.

But this time: Clang-tang, clang, whir-clunk.

The ball hit the rear of the rim, bounced up, bounced again, then dropped through the hoop.

John whispered, “That’s the closest to a miss I’ve seen. You best keep out of his way, Tim.”

*

On the open prairie, when the sun is bearing down, it can seem as though all living things are hidden or have moved on and taken up residence elsewhere. There are moments when the prairie appears to be downright inhospitable. But watch that field long enough and you’ll be sure to see someone or some creature toiling away, plodding along, fighting against nature’s ways.

*

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

And the man continued.

John, meanwhile, had come up with a counting system: for each made shot he used a graphite-like rock to scratch a line into the blacktop. For every five made shots, he’d slash a line across four so that he had them in groups of five. By the time the man made a hundred, John had put box around twenty groups of five.

“We should tell somebody,” Tim said.

“I don’t know,” John said. “Let’s just watch. This might not last long. What is anybody else gonna do anyway? And besides, how’re we going to tell somebody?”

Whir-clunk.

“I could tell my dad,” Tim said. “He’s home. It’s only a block away.”

Whir-clunk.

“You’re gonna leave in the middle of this?” John said. “Can’t you just enjoy it?”

“Dude,” Tim replied. “It’s a block.”

Whir-clunk.

“Okay. I’m leaving,” Tim said. “I’m going now. I can’t not tell Ol’ Tommy.”

“Fine,” John said. Then, as Tim started to hurry away, John added, “Wait, Tim. Take my bike. And hurry up.”

Not much time passed before Tim returned with his dad, Tom Dailey, an agent at the local Country Insurance office on College Avenue on the west side of town. He could talk for hours about auto, crop, or, especially, life insurance, or the benefits of annuities. But what Tom Dailey seemed to know about more than anything was local college basketball. He had retained and could recall from memory, with ease, the details about the lives of every young man or woman who came to town to play basketball for Illinois State University’s Redbirds or Illinois Wesleyan’s Titans in the past twenty-five years.

Tom Dailey patted John’s head and said, “Hey, Johnny Boy. What’s happening? Watching that man shoot, eh?”

“Yeah,” John said in hushed voice. “I’ve been counting his free throws for a long time now. He hasn’t missed a single shot yet. Not one.”

“Just like I told you, Dad,” Tim said, mimicking the boy’s hushed voice. “Here. Watch him.”

Whir-clunk.

“I see,” Tom Dailey said. “Well, yeah, that’s a beautiful shot. Love the form. He’s squared up nicely, has good leverage, wrist action. He follows through. Sure, it looks good.”

Whir-clunk.

“How many has he made?” Tom Dailey asked.

“Over four hundred,” John said.

“Four hundred!”

“Yup. Four twenty.”

“In a row, Johnny Boy? Four hundred in a row?”

“Yup.”

“Are you sure?”

Whir-clunk.

“I’m sure, Mr. Dailey.”

Whir-clunk.

“I’ll be damned. That’s unbelievable.”

Whir-clunk.

“Good Christ,” Tom Dailey said. He then pulled out his phone and checked the time, checked his calendar. He had three afternoon meetings, a couple meetings with long-time customers to go over household insurance portfolios and one with a potential client. The first meeting was scheduled to start in two hours. He put away his phone and looked at John’s counting system on the blacktop. “What have you got here…let’s see, okay, so you’re marking off by fives okay and that’s a hundred. Okay, I see. Okay. Okay.”

“Dad,” Tim said. “Shhhh…and watch.”

Whir-clunk.

“Yeah, Timmy. I see. That’s beautiful. That’s a beautiful shot right there,” Tom Dailey said. The shot was unfamiliar. He wanted to figure out who this man was, where he was from, and why he was here. This thing he had encountered did not make sense and Tom Dailey wanted to better understand the context, the reason he was seeing what he was seeing. “Have you talked to him…”

“Well,” John said, “I don’t think we should interfere.”

“No?” Tom Dailey looked at John, then at his son, who nodded in agreement. “I suppose you’re probably right, Johnny. You are probably right. Like a no-hitter happening live at Wrigley: we should just watch.”

Whir-clunk.

“I’ll be damned.”

Tom Dailey looked around at the empty schoolyard, at the jungle gym and swing set, then back at the free throw shooter, who was getting back to the line, about ready to shoot again.

Whir-clunk.

“But I’ll be damned, Johnny, Timmy, if we’re going to stand around and watch this thing by ourselves.”

Tom Dailey again pulled out his phone and rechecked the time, then started pressing buttons that pulled up his list of contacts.

*

The sun shone in the center of the sky. It seemed to be directly above the free throw shooter, providing a kind of spotlight.

The shot was unfamiliar. He wanted to figure out who this man was, where he was from, and why he was here. This thing he had encountered did not make sense and Tom Dailey wanted to better understand the context, the reason he was seeing what he was seeing.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

The man continued. He collected the ball from wherever it had bounced away from the net. He took it in his right hand, placed it on his hip, and strode back to the line, fixed his eyes on the basket. He dribbled three times, tossed the ball in the air to himself, bent his knees, then rose up, lifted his arms, and flicked his wrists releasing the ball from his fingertips—whir-clunk—his arms followed through.

Tom Dailey had walked off to the far corner of the schoolyard. He paced the blacktop, watching the free throw shooter and talking into the telephone, into his friend and Pantagraph reporter Frank C. Rollings’s ear.

“…if I weren’t serious, Frankie, would my name be Tom,” he said. “Nonstop, Frankie. Nonstop. And he hasn’t missed yet. Like a machine. Some kind of beautiful machine. Yes, three. Going on three hours. Since ten this morning. And…yep…yep, yep. I’ve been here an hour plus change…No, no. No clue. I have no clue. None. I mean, he’s not from around here, Frankie, not that I can tell. Definitely not an ISU or Wesleyan guy, you can tell that bastard Bludworth that.”

Whir-clunk.

“I mean, holy shit, Frankie. Just get over here already. This is it. What time does Bludworth need you to file your story by? Because this is it. I’m telling you: your story is here, Frankie. My son and Johnny Boy have got your story. Here, listen…”

Tom Dailey held the phone away from his ear for a moment, held it up toward the free throw shooter.

Whir-clunk.

“Did you hear that, Frankie? That was the sound of another free throw swishing through the fuckin’ metal net.”

Tom Dailey ended the call with Frank C. Rollings then called his assistant and rescheduled all of his afternoon appointments.

*

In the two o’clock hour the man paused his shooting routine twice. The first time he paused was so he could take a drink from his jug and the second time was to urinate behind the bushes along the schoolyard’s fenced perimeter. Each time, before he walked away from the court, he placed the ball on the free throw line, as though signaling to the onlookers that he was not stopping, only pausing for a break. Both times he returned to the ball, picked it up, and placed it on his hip for a moment. And then the man continued.

*

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

The group of onlookers had increased in size to twelve. First came Salvatore Vitali with his German shepherd, ‘Cisco. Sal lived in an old country-style house with a large front porch, a block over from the school, on Dale Street. He used to own and operate The Coffeehouse in Downtown Normal, but he sold the café for a handsome sum around the same time that Downtown Normal was being updated and rebranded as Uptown Normal by a group of civic and business leaders. Now, even though Sal had enough money to spend the summer on a coastal resort property, he spent his days tinkering around his house, or wandering around town visiting old pals or looking for excitement, just what he was doing on this day when he came across the group of onlookers who were watching this free throw shooter at the schoolyard.

Shortly after Sal arrived, the three Miller boys—aged 14, 15, and 16—and their next-door neighbor and closeted lesbian friend, Sarah Jackson, entered the schoolyard with the intention of shooting hoops, but instead, the group decided to watch the lone man shoot.

A half hour later, three septuagenarian Bobs (Thompson, O’Brien, and Woods), all retirees and longtime friends and neighborhood residents, arrived at the court. They were gathered at Zorba’s Restaurant having their weekly brunch when they had received a text message from Sal Vitali (a group text sent to Bob Thompson and Bob O’Brien but not Bob Woods because he only had a land-line). Sal Vitali had messaged the septuagenarian Bobs (Thompson and O’Brien) about the situation happening at the school and despite Bob Woods’s initial protests, the group of Bobs filed into their cars and moseyed on over.

Around the same time that the Bobs had arrived, Alexandra Lord, an adjunct instructor of philosophy at Heartland Community College and an exceptional amateur photographer, was on her daily afternoon walk. She saw the schoolyard congregation off in the distance and wondered what was happening, so she wandered over and soon became a member of the group.

The twelve onlookers were assembled at the court’s far baseline, sixty feet away from the man. The crowd was observant, spectating quietly, hushed in awe. Even Tom Dailey was now just watching in astonishment, not saying anything. Unless somebody new showed up, in which case he acted as the unofficial docent, explaining everything in detail. Tom Dailey would explain that the man who was shooting free throws, “seemed to be in some sort of trance.” He explained how it was best to observe the man with “a quiet respect.” He pointed out how the group had kept track of the consecutive baskets made by using the marks on the pavement. He gave a short run-down of how everyone did not know who the man was, but how John Fanning, “that one over there,” had seen the man arrive and start shooting baskets from the free throw line and had not yet missed a shot, how John Fanning told Tim, “that one there, my son,” about it, which is how he, “yours truly, Tom Dailey,” came to know about it, and how he told the newspaper reporter, “my good friend and writer for The Pantagraph, Frank Rollings,” about it.

The eldest Miller boy had posted numerous updates about the situation to his social media feed through his Twitter handle, @BallerForever. Most of his posts received little uptake, but the last tweet—one that included a photo of the man with his arm in the air following through on the shot as the ball whir-clunked through the net, a beautifully choreographed image—received twelve likes and three followers re-tweeted it to their followers. One of his followers replied, “It’d be great if that free throw shooter was live-streamed!”

*

In the late four o’clock hour, the northern sky became overcast, threatening a short storm.

The crowd, though, continued to grow. There were a few families with children who had visited the playground and then made their way over to the blacktop, plus several friends of the Miller boys. Due to sheer size, the crowd grew antsy and noisier. And the man continued.

Whir-clunk.

John Fanning sat on the blacktop, keeping the count, feeling amazed by the circumstance, and wondering about fate.

“How long will he go?” the youngest Miller boy asked.

Whir-clunk.

“How’s it even possible that he hasn’t missed?” Sarah Jackson said. “I once made fifty-three shots in a row, but…come on, this is ridiculous.”

“How come nobody knows who he is?” Sal Vitali said. “Tom, I want to know why you don’t know who he is.”

Whir-clunk.

“I can’t explain it, Sal,” Tom Dailey said, as he watched through teary eyes. “But I can say that this is beautiful. Just beautiful. I want to bottle this feeling up and sell it.”

Bob Woods said under his breath, “And then try to sell an insurance policy for it, am I right?” He chuckled to himself.

“Here is God,” Bob O’Brien said. “God is present. Here. Here, tonight.”

Around this time, Normal native and current ISU student, Teddy White, had stopped by. He had been passing through the schoolyard on his way from his parents’ home to his final destination of Milner Library where he was going to study for his summer class’s final exam. Before his study session, though, Teddy had planned on stopping at Avanti’s for a Gondola sandwich. But after watching the free-throw shooter for a half hour, Teddy said, “I can’t study. I can’t study when this is happening. Somebody tell me how I’m supposed to be motivated with this going on.” No one answered him. Teddy added, “I’ve lost my motivation and now that I think about it, also my appetite. I left home hungry and ready to study. Now I’m no longer hungry and cannot see a point in studying. Not when this is happening.”

Alexandra Lord sat in the shade of the school, reviewing photographs she’d taken. Her favorite shot might have been the one where the man was retrieving the ball after it bounced into the grass. The focus of the photo was the man’s legs. It captured an image of the man as he reached for the ball, with his legs slightly bent. The muscles looked particularly sculpted and the grassy area provided a nice contrasting greenish-yellow background. Alexandra Lord was already contemplating what to do with these pictures. She wondered how she might use them.

The clouds in the northern sky moved farther and farther into the horizon until they were gone. They never opened up to rain on the group.

*

Frank C. Rollings, longtime columnist with The Pantagraph, arrived on the scene and was immediately recognized by numerous people in the crowd judging from the murmurs and excitement.

Tom Dailey greeted him: “What’s going on Frankie, baby?”

“Tom-me!” Frank C. Rollings said. “How’re ya?”

Tom Dailey and Frank C. Rollings high-fived, then pound hugged.

“Now watch this Frankie,” Tom Dailey said, and they quieted down. Frank straightened out his face and put on a serious look. He squinted as he glanced around the schoolyard. He noted the presence of the high school basketball phenom, Sarah Jackson, and that there were close to twenty people gathered at the schoolyard. Then, he turned and watched the man dribble, toss up a spinning ball, catch it, then shoot.

Whir-clunk.

“You see that?” Tom Dailey said. “What a shot, eh?” Frank C. Rollings nodded and maintained a serious look. Then Tom Dailey’s voice lowered: “And still not a single miss. He’s still going really strong. This is insane. Just insane. Your story, Frankie.”

The context was unusual for Frank C. Rollings. Basketball in the summer, the blacktop court at a schoolyard, an informal event. But there was no denying that this was an interesting local sports story, right in Rollings’s wheelhouse. He tried and could not place the man. He was not too young, but perhaps not quite middle aged either. He looked familiar to Rollings, but only in the sense that he was an average sized man in shorts and a t-shirt wearing basketball shoes and shooting hoops. The man was not from around town, at least not a known basketball entity. Rollings wanted to talk with the man, to find out his history, to figure out what brought him here, and why he had put on this show.

“How many has he made?” Rollings asked.

Tom Dailey walked over to John, stood over his shoulder and counted the shots, then walked back over to Frank.

Whir-clunk.

“That’s seventeen-oh-five,” Tom Dailey said, then he pointed toward the free throw shooter, waved his finger down signaling the last shot was made. “Make it seventeen-oh-six.”

Frank continued to examine the mysterious man for several moments, not saying anything. Then he smiled.

Not long after Frank C. Rollings had assessed the situation, he made two phone calls. First, he called his editor, Bludworth. He left a voicemail message that, indeed, he had tonight’s story and that he’d be in the field till he did not yet know when. The second call he made was to his friend and colleague at the local CBS channel.

*

In the seven o’clock hour, the sun had shifted noticeably to the western horizon and yet, but for a few cumulus clouds, the sky was endlessly blue and there was still a lot of sunshine left. A group of crows cawed in the far-off oak trees. On the schoolyard blacktop, despite shifts in the makeup of the group—a father and child from the playground would leave and three more people would show up—it continued to grow in size. And the man, who the group was watching, he continued.

The man was not from around town, at least not a known basketball entity. Rollings wanted to talk with the man, to find out his history, to figure out what brought him here, and why he had put on this show.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

The local CBS TV affiliate arrived on the scene. The camera crew and reporter collected video clips of the man, the assembled crowd, an orange basketball laying stationary in the grass, the markings on the blacktop signifying all the made baskets, and interviews with witnesses, including conversations with a reluctant John Fanning, Tim and Tom Dailey, and an elderly man watching the scene from a red velvet chair on the front porch of his home located across the street from the schoolyard, Leonard White (no relation to Teddy White, the ISU student). After acquiring the video footage, the crew left the scene.

Around the same time the eldest Miller boy (i.e., @Ballerforever) posted to Twitter: “Some old dude has made 1800+ FT shots in a row & counting in Normal IL. #News #WildNews @Pantagraph Newspaper.”

*

As the sun was folding below a pink-orange horizon, Bob Woods repeatedly asked the other Bobs (i.e., Thompson and O’Brien) if they wanted to make it over to Pub II to catch the end of the Cubs-Cardinals game, but neither Thompson nor O’Brien took him up on the offer. Eventually Bob Woods said, “I’m going now,” and left. But he was gone all of about five minutes before he returned. He never even made it to his Cadillac parked out in the front parking lot of the school. The other Bobs ribbed him for a good five minutes because of his inability to go to Pub II by himself.

“Well,” Bob Woods said, untruthfully, “truth is I was just going to check in on the car.”

*

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

John Fanning continued to watch in awe as the man continued to shoot. He was growing tired and hungry, as all he had eaten was a package of Pop Tarts that an older neighborhood friend had brought him. Thankfully he had thought to bring a large water jug, so his thirst was held at bay. And though he grew exhausted, he felt a responsibility to continue to keep track of the made shots, to maintain his position as first witness. John Fanning understood that he was witnessing an unusual and special event. The type of experience that he could talk about to not only a television reporter, but to kids at school during the next school year, to his teachers, to his future children, grandchildren. But more than the responsibility and beyond his witness, though, John Fanning was awed by what he believed to be a beautiful experience. He had never before experienced something that he believed to be beautiful. But he was sure that this man shooting free throws, rhythmically, ritualistically, continuously: it was beautiful.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

John Fanning started to cry.

*

Dusk arrived. Lightning bugs blinked on and off across the schoolyard. Grasshoppers chirped out a chorus. The moon shimmered, a white crescent stamped on the darkening blue sky. A faint buzzing sound emanating from a streetlight off in the distance could be heard. As sunlight faded, a nearby security lamp produced enough light that the group could still see across the blacktop.

And the man continued.

*

An aged woman in the neighborhood had called the police to complain about the schoolyard ruckus that she had seen (“Well, no, it isn’t that they’re noisy, but they look suspicious,” is what the caller said to the operator). Officers Collins and Bachman arrived at the schoolyard and were prepared to start barking orders at whoever they found spotlighted by their flashlights. They were ready to force everyone off of the schoolyard’s property. Then, Tom Dailey approached.

“Officers,” he said. “Good evening. You have come just at the right time!” He introduced himself as the agent at the Country Insurance agency off of Towanda Road and College Avenue and he gave them his business card. He said he knew Chief Kinnaird. That they should just check in with him, that it’d be okay. But they were unmoved. Then Tom Dailey explained the situation. Officer Collins looked around at the crowd. He recognized Sal Vitali. They waved to each other. Then Officer Collins nodded to Officer Bachman, who said, “Okay. This looks innocent enough. But I want you to all clear out when this is over. I don’t want any more calls coming in over my radio.”

“Thanks, officers. Thanks a lot,” Tom Dailey said. “Before you go, watch this…”

The officers watched the free throw shooter. They watched as he dribbled, tossed the ball in the air, and caught it. They watched him bend at the knees, then rise up and shoot. They watched the ball arc through the air.

Whir-clunk.

“It looks like you all could use some more light back here,” Officer Bachman said.

Whir-clunk.

“I think we could help,” Officer Collins suggested.

Whir-clunk.

John Fanning had given up his position as counter because he had become too exhausted. Now he was just watching the man shoot, mesmerized, feeling proud that he was there at the school when the man first arrived. Whenever new people showed up at the court, someone pointed out John’s special status as the first witness to the action. Roger Kaminsky, a childhood friend of Tom Dailey’s who still lived in nearby rural Danvers, had taken over the counting position.

Frank C. Rollings had called his colleague at the CBS affiliate and told him that not only is the free throw shooter still going strong, but there was also now a large and growing crowd at the schoolyard court. “Get back here,” he said. “This thing isn’t ending.”

*

Over in the grass a feral cat darted across the schoolyard, unseen. Officers Collins and Bachman had driven the cruiser around the school and had pointed the vehicle’s spotlight on the court.

And, despite the late hour, the man continued.

Whir-clunk.

*

Tom Dailey sat on the blacktop, his head shaking after each made bucket, revealing his continued sense of astonishment.

Roger Kaminsky, the current keeper of the count, became tired, but still refused several offers from others in the crowd who offered to take over. “Look,” Kaminsky replied, “I didn’t come all this way to get tired now when I’m needed. No. I’ll stay the course.”

*

The CBS crew had returned to the scene. Now, though, that crew was joined by the local NBC and Fox affiliates, and national media outlets, CNN, WGN, and ESPN, were each live-streaming the action with the help of independent journalists and on-site social media users. After each shot, the intensity at the schoolyard continued to build, as did the noise levels, with the various videographers and newscasters setting up lighting, arranging reports, chatting amongst themselves, making a racket, despite the repeated attempts by observers in the crowd to quiet down the noise.

Local high school and college sports fanatic, Matt “The Cat” Adams, had arrived to the schoolyard now too. He had watched the 6 o’clock CBS news report and, not knowing if the action was still happening, decided to take a chance and walk over, a white towel in hand, ready to wave it in celebration of each made basket.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

Whir-clunk.

The Cat, his head bowed slightly, was waving the white towel with vigor. The crowd’s long-timers felt rejuvenated.

*

Stars were visible in the darkened sky. In the far-off distance a satellite received and delivered bytes of information that the social media users and respective press members had been collecting, organizing, and transmitting for the entertainment and consumption of people all across the world.

And the man continued.

*

CNN’s correspondent estimated that there were nearly three hundred people at the scene. A father, who had come to the schoolyard with his two teenage children from East Peoria, was interviewed on CNN. “Look,” he said, “We’re a basketball region. And I consider my family to be a basketball family. If there’s an important basketball event nearby, I’m going to be darn sure that I give my kids the chance to be part of it. So, we came over to witness this.” A family from Chicago who were visiting relatives had also made it to the schoolyard. In an interview, the mother said, “I grew up watching Michael Jordan and the Bulls. I remember where I was when Jordan hit his famous shot in Cleveland—the first and the second time. I remember where I was when the Bulls won the first championship in L.A. I remember where I was when MJ announced his retirement, when he announced he was coming back…look, in life there are certain moments, moments where…such as where were you when we landed on the moon moments. This schoolyard, this free throw shooter, this is one. I am just so happy that my kids are getting to experience this with their cousins. This is great.”

John Fanning had grown even more exhausted and awed. When word was passed around the crowd that the free throw shooter’s streak had reached three thousand, one hundred and twenty-six consecutive free throws made, John, again, was overcome with emotion. This time he was not the only one in the crowd. His pal, Tim O’Brien cried too. As did Frank C. Rollings, the first time he had been overwhelmed and cried in response to a sporting event that he was covering as a columnist. Tom O’Brien placed his arm around his son, Tim O’Brien, and, for first time in recent memory, Tom was speechless.

*

Whir-clunk.

The man retrieved the rebound, placed the ball on his hip, and walked back to the line. He eyed the hoop, then closed his eyes, tilted his head to the sky, paused.

This was not the routine that the man had been going through since they started watching. A collective “Ooh” was heard ripping through the confused crowd.

Newscasters readied themselves for something dramatic.

The man, though, remained standing at the line, with his head facing the sky, his eyes closed.

John Fanning stood up and walked toward the man. He entered a space surrounding the man that no one had entered since Tim attempted to rebound the ball nearly thirteen hours ago. Just why he moved toward the man, John didn’t know, but it felt necessary to him.

As he approached the man from behind, the man lowered his head and opened his eyes. He then slowly bent over, kneeled and placed his hands on the ground. He leaned over and brought his head to the blacktop. His lips kissed the line, then he staggered to his feet and faced the boy.

“Are you…” John started, but then stopped, not finishing the thought.

The man smiled, reached out and placed his hand on John’s head and rubbed his hair. He handed John the ball, then walked away from the line, toward the baseline, to the water jug, the bag. He collected his things, then started walking away from the court.

The press and others in the crowd descended on the man.

“Who are you?” they shouted.

And, “What’s your name?”

“Are you done shooting?”

“Where are you from?”

“What was this all about?”

“Why’d you choose this court?”

“Where are you going?”

As the man walked away, he looked straight ahead and remained quiet. The mob of reporters surrounded him, making it difficult for him to walk. But he kept moving and didn’t answer their questions. He walked, going around the school till he reached the adjacent street, Adelaide. He turned onto Adelaide and walked on. And, with the crowd behind him, asking questions, staying on his tail, the man continued.

*

The next morning John Fanning returned to the schoolyard with the ball that the man gave him. When he arrived at the court, he replayed the man’s routine in his mind: the dribbling, the tossing the ball into the air, the bending of the knees, the raising up, arms extending, wrists flicking, fingers releasing, the follow-through. And he heard the whir-clunk.

Then John walked to the line. He tilted his head toward the sky, closed his eyes, and he paused. Eventually he would open his eyes. Eventually he would eye the hoop. He’d dribble the ball. Toss it up, to himself. Bend his knees. Eventually he’d take a shot. Eventually. But for several moments he just stood at the line, enjoying the feeling of the sun shining on his face, enjoying how with his eyes closed all he could see was an abstract painting of bright orange-red with streaks of moving black shadows, enjoying the beauty that he saw.

STORY:

Peter Witte is a writer, visual artist, and former basketball player (he retired from playing pickup ball in February 2020). His writing has been published by The Threepenny Review, The Sun, and Tin House Online, and more recently in West Branch, The Bureau Dispatch, and HAD. He grew up in the basketball hotbed of Central Illinois, but now lives in University Park, Maryland.

*

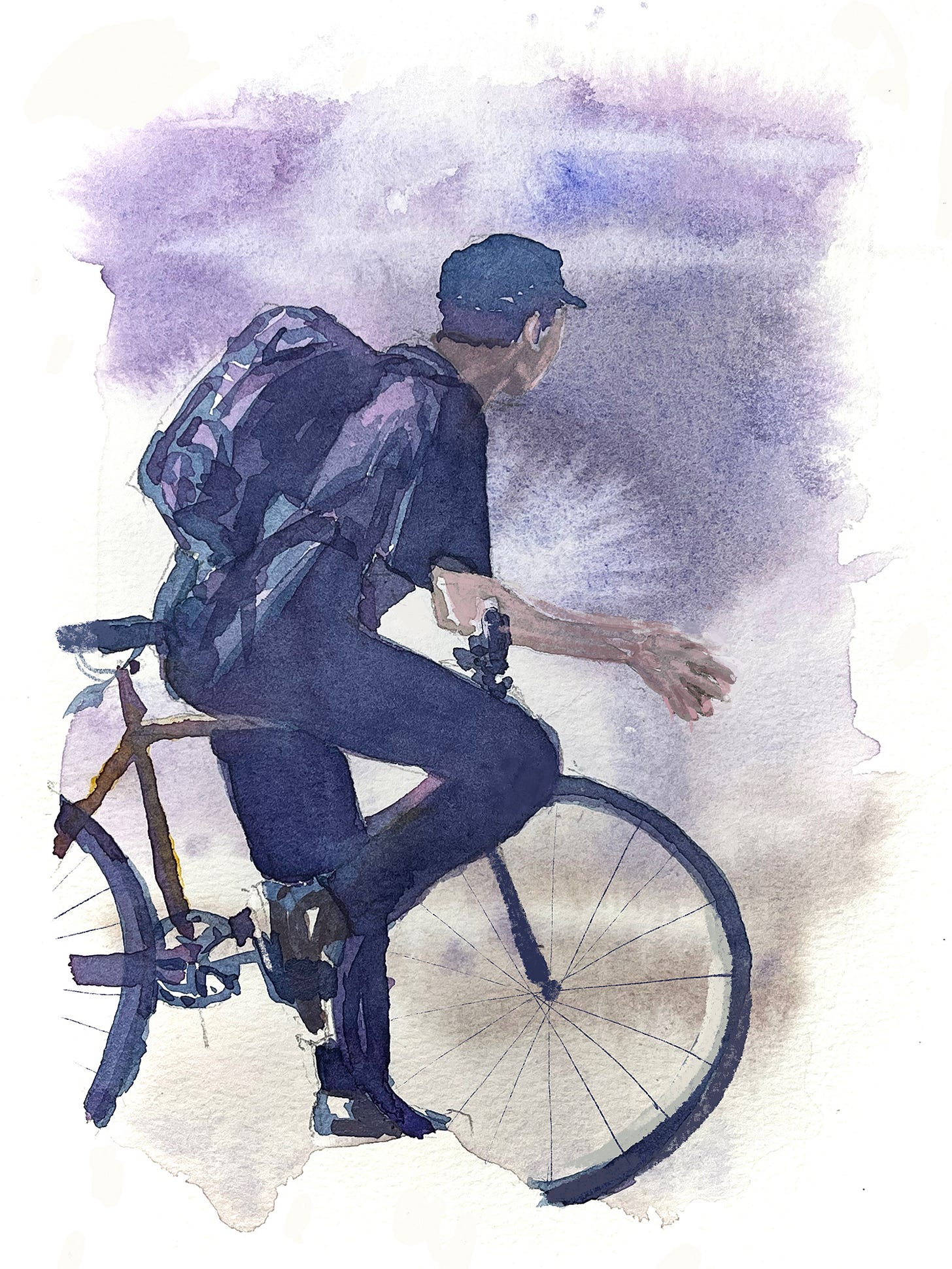

ART:

Jiksun is a painter and writer from Hong Kong. His stories have been published and recognized in the SmokeLong Quarterly Award for Flash Fiction, The Molotov Cocktail Winner’s Anthologies, Wigleaf, Atticus Review, and elsewhere. His art is featured or forthcoming in Barrelhouse, Flash Frog, and a mystery novel to be published in 2025. He and his wife share their home with two daughters and enough crayons to last a lifetime. Find him on socials @JiksunCheung and http://jiksun.com.

Next Tuesday, we’ll feature a bonus interview with Pete about this story!

What a wonderful story. Thanks for publishing it!

“On the open prairie, when the sun is bearing down, it can seem as though all living things are hidden or have moved on and taken up residence elsewhere. There are moments when the prairie appears to be downright inhospitable. But watch that field long enough and you’ll be sure to see someone or some creature toiling away, plodding along, fighting against nature’s ways.” Omg ❤️