"Swans" by Amy Stuber

"This is a story about Peter’s first year of college. No, it’s about boys and birds and men. Or it’s about love and safety and the ways we hurt each other."

I’m so excited to get to feature this one today.

Amy Stuber’s collection, Sad Grownups, was one of my favorite books of last year. I read it slowly, the way I do all my favorite collections — one story a day, savoring it. When I finished, I added it to my favorite bookshelf, the one reserved for “favorite story collections of all time.” I’ve been raving about it and recommending it since, many of these conversations turning into friends agreeing that it was one of their favorite books from last year as well. I taught one of the stories from it, “Cinema,” earlier this semester, and it has been a treat every time it comes up in class conversations, something we’re reading or talking about reminding a student of our discussion of it earlier in the semester.

There is so much in this story to admire — the voice, the sentences, the way Stuber can twist and turn and unfold a story in ways that always surprise me while also feeling so inevitable and just right — but I also almost don’t want to say too much. I just want you to read and admire it, too.

I don’t want to overstate, but stories like this are a big part of why I so love being an editor. Getting to share them with readers. Getting to be a small part of helping bring art into the world. I’m excited to get to feature this one today. I’m excited for you to be about to read it.

—Aaron Burch

“Swans”

The night in question, Peter Thornton stood at the bar, his head so near the purple lights that hung down from the ceiling on wires that his hair glowed.

Girls wore stretchy dresses and fake eyelashes and block heels. One of them leaned close to Peter. She said something he couldn’t fully hear because of the music, and he laughed and then realized maybe he wasn’t supposed to laugh. She walked away to the bar and huddled with a group of friends whose white-painted fingernails flew sharp through the air as they talked.

“Bro, you should fuck her,” one of his horrible roommates said, and Peter walked to the bathroom where someone had carved “Franz has herpes” into the wall above the farthest urinal.

Peter had only had sex with one girl, a couple of years before college. She’d worn black Vans everywhere and her brother’s t-shirts with airbrushed pictures on them of American flags and pickup trucks. “I’m wearing these ironically,” she’d said the first time they talked. “You know that, right?” He hadn’t known that. When she moved away after a few months, which everyone did because the town where he’d grown up was dying or dead like all the little towns in Kansas that didn’t have plastics factories or feed lots, he’d proceeded to spend six months in what his sister had called a regressive vegetative state, during which he ate microwaved food and played Minecraft for hours like he was once again nine years old. But then we all do this over decades: grow up, fall apart, grow up, fall apart, die.

This is a story about Peter’s first year of college. No, it’s about boys and birds and men. Or it’s about love and safety and the ways we hurt each other.

Peter had only very recently started trying to think of himself as a man instead of a boy, and that was awkward and didn’t fully fit.

When he came back from the bathroom at the bar, his roommates were high-fiving each other and holding empty shot glasses in their hands.

“Yo, Pete,” one of them yelled. Cooper or Cooper or Anders or Brody or Marcus. Peter nodded but didn’t walk over. There were no dart boards and no pinball machines. Had they been there, Peter might have occupied himself with games. One of the Coopers started dancing with the same girl who’d talked to Peter. He was a terrible dancer, but nobody seemed to care. Soon, almost everyone was dancing and holding plastic cups up and jumping up and down, and the music made the rows of glass bottles behind the bar tremble.

In high school, when Peter had imagined himself at college, he’d thought he’d end up at parties with artists or musicians or maybe even kids who stayed up late talking about things like quarks. Instead, he was living in a group house with five sophomores, one of them the cousin of someone his sister knew. All a year older than he was, all sophomores, all barely hanging onto their C averages, all drunk on most days, all decent but not as good as he was at basketball, all who would probably in five or eight years live on Midwestern streets named after things far more grand than the streets actually were (Castle Court, Eagle Ridge), sitting in plastic Adirondack chairs after working in something like garage door sales, drinking some big chain beer company’s faux craft beers. Men, they would be men.

Peter had only very recently started trying to think of himself as a man instead of a boy, and that was awkward and didn’t fully fit. He wasn’t adept at back slapping or shit talking or bro hugging. He was 6 foot 5, usually the tallest person in the room, but he didn’t have a full-time job and lacked the bravado of people like the two Coopers, for example.

It was his first time away from the small town in Kansas where he’d lived with his mother and his sister who hadn’t gone to college but had instead gone to hair school and now did hair for old women who wanted the same hair they’d had for fifty years. This meant a lot of perms and sets instead of the balayage and unicorn hair she wanted to do. It was okay, she told Peter. She could smoke weed in the alley behind the shop and then mist herself with essential oil before going back inside so the whole day became a pleasant blur, and she could smile and nod at all their old-lady stories and then go home to watch shit tv with their mother. It was all, she told Peter, fine.

The night in question was one of those weirdly warm October nights that tricks you into feeling like summer. Peter could see the moon out the one window by the bar’s back door, and he thought about leaving. At the edge of the dance floor, the taller Cooper moved onto a stool with the girl. He hoisted her on his lap. His movements were angular, and she didn’t look comfortable. Still, he said something, and she laughed and threw her head back, so her hair trembled down toward the floor.

Marcus walked over to Peter and said, “I’m starved. Let’s get some food.” Marcus had moved in after Peter, late in September, as a replacement for one of the roommates who’d had to move home when he found out his dad was sick. Marcus was, like Peter, not a real friend of the Coopers, and he was the only one of the roommates Peter tolerated and even liked.

Neither one of them had a car, so they grabbed two of the shared town bikes that someone had left leaning against an iron railing outside the bar. Peter followed Marcus, and they rode over the bridge and along the levee path by the river. They heard trains and trucks and cicadas and crickets and someone screaming in a happy way under the bridge.

They rode and felt like balloons, floating, not having to think about how to be. Love and the future didn’t matter. They rode outside of town on the farm roads, and it was loose-edged abandon and everything Peter thought about wanting when he was a kid and felt hemmed in by house and closed windows.

There are moments in childhood when you don’t think of protection, when you’re so safe you don’t have to think about safety. For Marcus, maybe that was being in his mom’s kitchen. Maybe on the wall above the table his mom had hung tiny sketches of birds, finches, starlings, catbirds, robins, everyday birds, window birds she’d drawn with his elementary school colored pencils, and they were meticulous. Maybe she was making hot chocolate from syrup and milk in a pot. His sisters were lying on the tile and sketching castles, and the room was a little too warm in a good way that could make you feel happy and drowsy at the same time and like the room was the whole world and all Marcus would ever need. And maybe that safety was love.

For Peter, safety was outside and flying on his bike on the path by the railroad tracks where trains came infrequently but when they did, it was a close wild rush of noise that shook his whole body, and he loved feeling like he might topple but knowing he wouldn’t. Maybe that safety for him could be outside and alone, and maybe for Marcus it couldn’t, or maybe not in the same way. Or maybe Peter was wrong. What did Peter know of Marcus’ life or of Marcus? Almost nothing.

When they rode back into town, they went to the one place still serving food and ordered far more than Peter should put on the credit card his mom had given him for emergencies. They worked through a whole table of food, pancakes and waffles with whipped cream and hash browns burnt at the edges and strawberries in a jadeite bowl and scrambled eggs piled high on a chipped white plate. When almost all the food was gone, they both leaned back on the vinyl of the booths and looked up at the tin ceiling and said nothing but felt content and good.

There are moments in childhood when you don’t think of protection, when you’re so safe you don’t have to think about safety.

Peter’s English lit teacher had assigned a story about swans during the second week of school: “The Swan as Metaphor for Love.” The teacher seemed like someone his sister would be friends with. She wore political t-shirts and changed her hair color frequently.

“Tell me what this means to you,” his English teacher said to the class. This was exactly the kind of assignment he hated. Not “tell me what this means,” which he could do, but “tell me what this means to you,” which suggested something more personal that he was usually unsure of or uncomfortable disclosing. He printed the story and carried it with him and read it a few times when he walked to and from his house.

The story was supposed to be about love. Anyone could tell this from the title. But it was also about swan shit and pond scum. He’d seen his dad leave their house forever one morning after years of professing his love to his mother in all kinds of embarrassing ways. Did he need to read a story about swan shit to know love was rough?

Or maybe the story wasn’t about romantic love but was some kind of statement about swan people, the ones who look or talk a certain way and thus get away with everything right under our noses because they can.

This, the reading and rereading of the swan story, was all before Marcus.

For reasons he couldn’t or wouldn’t articulate, it made Peter feel good to see Marcus in the kitchen, to walk to class with Marcus, to be in the diner late-night with him. He could imagine one of his other roommates saying something like, “Come on, man, I have a Black friend,” like saying it out loud to win some conversational battle about whether they were or were not racist. And Peter would never say that, but then there he was, sitting in a diner at 2 AM, feeling a little puffed up by the sheer fact of the proximity of Marcus. When he realized it, he felt ashamed.

They left the bikes leaning against one of the downtown planters and walked the few blocks back home, past the record store with its cats prowling around the window display of vintage amplifiers, past the bike shop with metal water bottles lined up on a rectangle of astroturf, past the glasses store almost no one could afford, past the bank that told the temperature and time over and over, and all the way to the house where Peter’s room was at the front of the house and where, even in the dark window, he could see the failing jade plant his sister had brought him the week before when she’d visited.

For a while, they played a video game in Marcus’ room. Peter was on a blanket on the floor and Marcus on the bed, with the LED lights running their cycle from red to blue to green to purple and back again.

Was there a way, Peter wondered, to find another apartment with just Marcus? To get away from the others who he knew looked at him and saw motels and desperation, not country clubs, not languishing mothers on expensive lounge chairs. When he thought of his childhood, though, he thought of the silver Christmas tree his mother had decorated with origami birds they spent a couple of weeks folding each night while listening to 90s hip hop. Or the hummingbird feeder she bought at a hardware store when he was seven or eight that hung outside their kitchen window every summer until he left for college and where hummingbirds that weighed less than a penny would dart at each other, and they were nothing like swans in their shape and size and style of movement but still had some essential grace and delicacy.

The last thing Peter did before falling asleep on the floor of Marcus’ room was text his sister to say, “I had the best night.” Maybe this, this feeling of being sated and cocooned with someone who makes you not worry about yourself, was love.

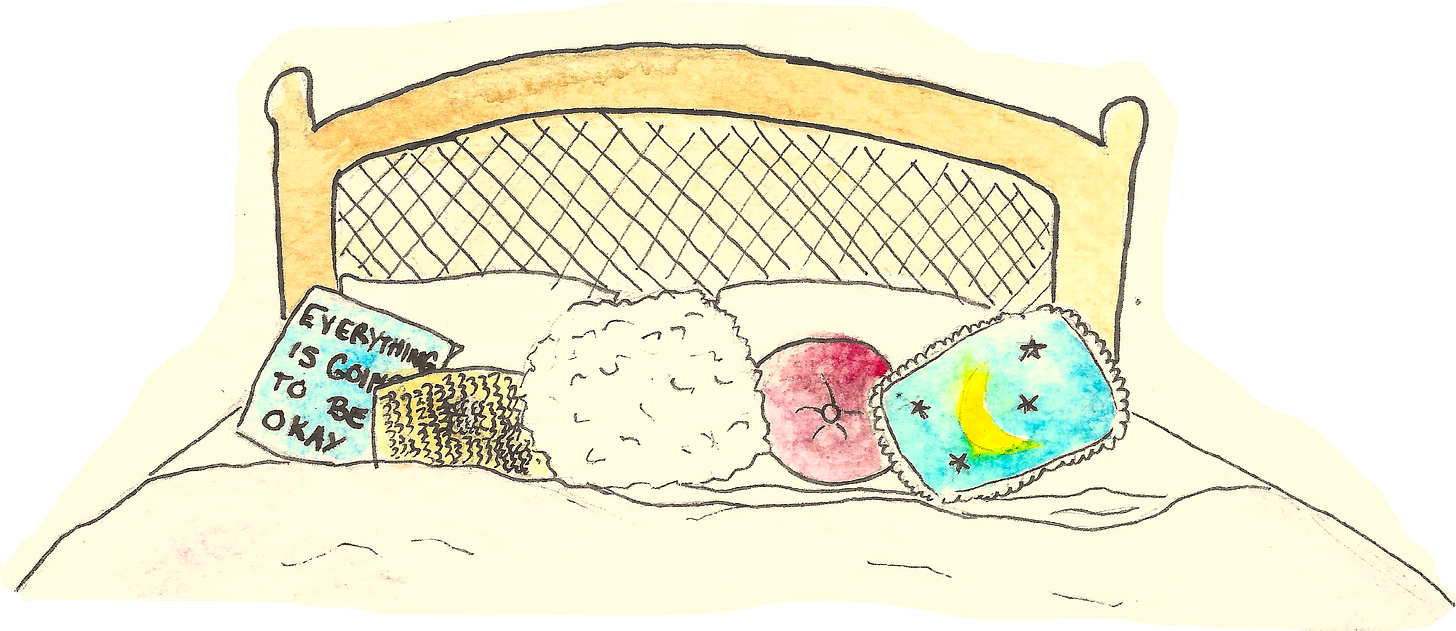

On the night in question, the girl from the bar who’d sat on the lap of one of the Coopers walked home, her dress dirty, one of her shoes broken, at 2 or 3 am and took the longest shower. After the shower, she went from wobbly to completely sober and then sat awake on her bed surrounded by all the throw pillows she’d picked out with such precision and intention with her mom before bringing the carload of her things to the door of the place where she would live for the first time away from home. The sequined pillow that was gold when you pushed it one way and silver when you pushed it another. The shaggy white fleece pillow. The one with the moon and the stars stitched onto it in blue and yellow. The one that said in white against a pink background “Everything is going to be OK.” When she finally called her mom, the light from outside was making her window glass shine, and her mom got in the car, turned on maps to tell her all the turns so she wouldn’t have to think, and called the police. “I don’t know,” the girl said when her mom showed up at the door of her apartment a couple hours later and asked her for all the details of what happened. The girl looked at the sliding glass door and tried to think of the order of things, tried to call to mind the face of the person on the bar stool, the person who pushed into her in the bathroom. She held her hands tight together, looked away from her mom and said, “I know something happened. But I really don’t remember much of anything.”

The last thing Peter did before falling asleep on the floor of Marcus’ room was text his sister to say, “I had the best night.” Maybe this, this feeling of being sated and cocooned with someone who makes you not worry about yourself, was love.

Peter and Marcus were fully asleep with the black-out blinds pulled down when it was morning, and the police car pulled in front of their house, when two police officers came to the door, and one of the roommates let them in.

When Peter woke on the floor in Marcus’ room, his legs were sore from biking, and his stomach was knotted up from the food and the alcohol. Marcus was still sleeping in the bed, and his mouth was knit shut, but his face looked happy enough. His eyes were twitching, and who knew what he was dreaming.

Peter thought nothing of all the heavy feet on the wooden stairs. They were old stairs in an old house where everything creaked.

A car screeched outside, and the taller Cooper stepped into Marcus’ room, over Peter, sprung up the roller blind, and the whole room was bright. Birds fussed near the half-opened window.

Marcus snapped his eyes open, sat up in his bed, let his gaze land on each of the men in the room. His face looked in that moment like he wasn’t surprised at all.

A better man than Peter would have spent an hour with the police going over the facts of the night. But Peter got up, left the room, vomited in the bathroom, and then made his way down the back steps. He grabbed his dirty running shoes and first walked and then ran all the way into the cemetery at the far eastern edge of town where there were crows everywhere. Brash and insistent, swooping, cawing, no grace, no subterfuge. Think what you will about love; sometimes it isn’t enough. Sometimes it doesn’t even matter.

At the center of the cemetery, the old kind with shaggy pines and oaks that are a hundred years old, he lay on the hill and counted backwards from a hundred. He didn’t believe in ghosts, hadn’t at least, but that morning he felt them: all the people that had been and were no more, a chorus of tsks and sighs, reminding him he knew nothing about loyalty and love, knowing before he did how he’d walk home, slowly, and once there say absolutely nothing.

STORY:

Amy Stuber is a fiction writer living in Lawrence, KS. Her debut collection, Sad Grownups, was published in 2024 and was recently longlisted for the PEN Robert W. Bingham award. She is online at www.amystuber.com.

*

ART:

Nikita Andester is an author and multimedia artist living in Toulouse, France. She runs Snail Mail Sweethearts, a Substack about history's juiciest correspondence featuring monthly microfiction and original artwork.

Next Tuesday, we’ll feature a bonus interview with Amy about this story!

Oof. This one was a gut-punch.

That's a really good piece of writing. Nicely done.