Rosie, by Annie Earnshaw

"On my first night as a junior counselor, caught between my high school graduation and my impending gap year, I sat in the middle of a circle of the counselors as they deliberated possible nicknames."

There’s something about a camp story. Groups of kids away from home and parents, the world and life often seeming so exciting and magical but also hard and full of the unknown. The beginning of this story immediately grabbed me and pulled me in with its confident voice, shooting me into this world—a young girl at summer camp as a junior counselor the summer after high school, given as a camp nickname a moniker she doesn’t understand and isn’t sure if it fits her or not—and kept me right at that camp alongside all the campers through every beat and movement of the story.

Incredibly excited to get to share “Rosie” today!

—Aaron Burch

On my first night as a junior counselor, caught between my high school graduation and my impending gap year, I sat in the middle of a circle of the counselors as they deliberated possible nicknames, fishing for the one that stuck. Leapfrog, Toenail, Lantern, Biscuit, Cactus. Nothing quite fit until one of the senior counselors over my left shoulder, a girl a few years older than me with red hair and a blue headband, shouted “Sparky” in a clear, confident voice. The group went quiet, pondering whether Sparky was the name for me. Did it fit my personality? My look, my overall demeanor? A beat passed, then the senior counselors started to clap and cheer. I took that as a sign to rejoin the circle; someone I didn’t know patted me on the shoulder in congratulations.

As they christened the next junior counselor, I found myself studying the girl who’d named me. Her lips pursed like she was eternally blowing a kiss and even though her hair was thin and straight, it still sprung out of the bun on top of her head like she’d just stuck her head out a car window. She wore mismatched socks under her Birkenstock sandals and had tarnished silver rings on each finger, a chunky turquoise ring on her thumb.

After the rest of the counselors had been named, Paul, the camp director and lead pastor, shared a blessing and dismissed the meeting. I thought about weaving through the crowd to find her, ask why she’d picked Sparky. But I was tired and slightly afraid of her confidence, how she perpetually looked like she knew a juicy secret and was on the verge of divulging. She seemed like the kind of person who would be a great mom but didn’t want kids of her own.

*

The third week of the summer, when I showed up to the cabin where we’d be bunking for the next week, the girl who’d named me Sparky stuck out her hand, all rings and bracelets on skinny freckled fingers and wrists, and introduced herself. “Lego,” she said. She was my senior counselor for the week.

“Nice to meet you,” I said, looking down at the piles of stuff in my arms and trying to figure out if there was a way for me to return her handshake.

“You’re Sparky, right?” she asked, returning to her bunk and continuing to unpack. She had two of those cheap plastic drawer towers that fit perfectly under the bed and a bottle of laundry detergent, which was prohibited. My other two senior counselors had used the same system and carried the same contraband.

I couldn’t figure out if she was asking my name out of formality or because she’d truly forgotten. I said “yeah” and kept settling in.

As I swung one of my bags onto my bed, my birth control packet flew out of the side pocket and skittered across the floor, landing on Lego’s side of the cabin. She was reclined on her bed, one leg dangling over the edge of her mattress, but the noise made her look up from her book, The Picture of Dorian Gray. She wordlessly kicked the pills back across the gritty concrete, lazily thumbing at the page corners of her book.

Our campers arrived the next morning, a group of mismatched twelve-year-old girls at vastly different stages in puberty. Some were still soft with elementary school chubbiness, others already made of long, gangly limbs they couldn’t quite control. The three or four girls who thought they were popular magnetized together almost instantly, leaving the rest of the introverts to awkwardly stand in each other’s proximity, waiting for someone else to break the silence.

It hurt to see how quickly they could isolate each other. I’d seen the distance between girls like them my past two weeks as a counselor and every other time I’d come to camp as a kid. They started out awkward, timid, and would grow to know each other fully by the end of the week. It was so different from our eight-year-old campers who still hung onto that childlike desire to play with whatever kids were in their radius.

But that was why Lego and I were here: to help these girls relearn how to play with each other. To help them be kids, if only for a week.

After our nine girls all checked in and their parents finally left, Lego led the group up to our cabin. Most of the girls brought duffel bags that they could sling over their shoulder, but one of the campers brought a rolling suitcase, which was largely incompatible with the gravel path up the hill to our cabin.

“Can I help with that?” I asked, falling back to check on her. If I remembered right from check-in, her name was Gia. She had a little brother in the nine-year-old group.

Gia looked up at me, breathing hard but trying not to look it. “I’m fine,” she said, a little breathless. Little beads of sweat formed on her hairline, sticking her baby hairs down to her forehead. She wore khaki Bermuda shorts and a t-shirt that fell to her mid-thighs. Even an extra inch of fabric in this summer’s weather could send someone into heat stroke.

“Here,” I said. We were only a few cabins down the path from our home for the next week and I could tell that she was putting on a façade to look tougher than she was. She may not have wanted the help, but I stepped behind and picked up the tail end of the suitcase while she hung onto the front handle.

Gia looked back in quiet relief. “Thank you,” she said with the practiced cadence of a kid whose parents had drilled polite phrases into her vocabulary.

“No problem.”

Once we got to the cabin, Lego and I let the girls settle in while we sat on the front porch, going over schedules for the week and sitting in the two rocking chairs outside the door.

“I think we should surprise them with big zip on Wednesday night,” Lego said, her feet propped up on the railing so the rocking chair rocked all the way back on its tracks. “Can you sign up for the slot next time we’re down at the big house?”

I nodded in agreement. There was a not-so-secret zip line in a field on the back edge of camp that was easily five stories tall and a quarter-mile long. It was unspoken tradition to wake your campers up in the middle of the night, hike them out to the field, and take turns hoisting them up to zip down the line.

“Did you go to camp here, Sparky?” Lego asked when I didn’t say anything. I’d noticed in my short time as her junior counselor that she tended to change the subject when the conversation went quiet. What was it like to have so many topics of conversation stored in her head at one time?

“For a few years,” I said. “I stopped when I was thirteen.”

“But you came back.”

I nodded.

“Why?” It struck me how plainly she asked. No elaboration, just why.

I chewed on the inside of my lip, then told myself to stop. There’s really no cute way to chew on the inside of your lip. “Didn’t want to babysit my little brother all summer.”

“So you came here to babysit other kids all summer.”

The idea sounded stupid when she pointed it out. My brother was a literal baby, an actual eighteen-month-old who was starting to grow out of his cute baby phase but wasn’t old enough to be fun yet. I’d been an only child for so long that he didn’t really feel like my brother; he was the result of my mom and her second husband. I think they wanted a baby as a way of avoiding their mid-life crisis.

“At least we get different kids each week,” Lego said when I didn’t respond. “Not like being stuck with the same one for a lifetime.”

The three or four girls who thought they were popular magnetized together almost instantly, leaving the rest of the introverts to awkwardly stand in each other’s proximity, waiting for someone else to break the silence.

Our first two days were filled with activities so the girls didn’t get homesick. Tie dye t-shirts at the craft shed, the human knot game where we all grasped random hands and had to untangle ourselves. Lego ended up grabbing my wrist and after twenty minutes of trying to untangle the knot, her rings and bracelets left imprints on my forearm.

At the low ropes course, our entire group had to inch across a wire suspended between two trees, gripping each other’s elbows for support. The girls played four-square at the pavilion while the snack bar was open. They’d spend their money on Crunch bars and cream sodas that came in antiquated glass bottles and had to be popped open on the bottle opener mounted to the wall. They navigated each other like asteroids in orbit, circling but never truly intersecting.

Tuesday afternoon, Lego and I taught our campers how to play swamp canoes. We loaded them into canoes and fitted them with life jackets that smelled strongly of mold and bleach, then sent them out onto the lake (which was really more of a glorified pond) with halved milk cartons. The goal was to flood other canoes so they’d sink, tipping the other teams out into the water.

Lego sat in the back of our canoe, steering. After we pushed off, she leaned forward so her head almost rested on my shoulder. “We should let them sink us,” she said, conspicuous like it was a secret.

I turned my head to agree and felt a little flutter in my chest when I noticed how close her face was to mine. I’d always planned on being the first team to go down; it gave the campers something to unite over. Seeing your counselors fall out the side of a sinking boat was an easy laugh.

Lego steered us toward a shallow cove on the other side of the lake where one of the boats was waiting out the weak competition. Katie and Layla, two of the quieter campers, started shoveling water into our canoe and I splashed enough water into theirs to look like we were a threat. They forced us out into the middle of the lake, attracting the attention of the rest of the boats.

After another few minutes, our canoe looked more like an aquarium than a boat. The unsteady canoe pitched us out into the water. Lego and I surfaced, breathless and smiling, as the rest of the girls cheered at our demise.

The girls started to open up after that. At dinner that night, Layla pulled out a deck of cards and taught a few other girls how to play Texas Hold-Em. They swapped out ten-dollar bills for rolls of quarters at the snack bar and used the coins as chips, but Lego made them promise that everyone would get their money back at the end of the game. We stayed long at dinner, letting them finish up their game and promising the clean-up crew we’d take care of our table if they left us some rags.

That was always one of my favorite moments at camp, the opening up of their personalities, the relaxing of barriers. Like they’d unclenched their jaws and unrolled their fists and, finally, let themselves take up space.

Wednesday night, I startled awake to a hand shaking my arm. My heart felt like it fell out of my chest and my eyes flew open to find Gia, crouching next to my bed in the dark.

“What’s wrong?” I whispered, my voice still edged with adrenaline.

She opened her mouth to speak, but no words came out. Instead, she turned and walked toward the middle of the cabin.

I tossed aside my blanket and got up to follow her. Soft light came from beneath the curtain that closed off the bathroom. As my eyes adjusted, I saw she’d wrapped a towel around her waist.

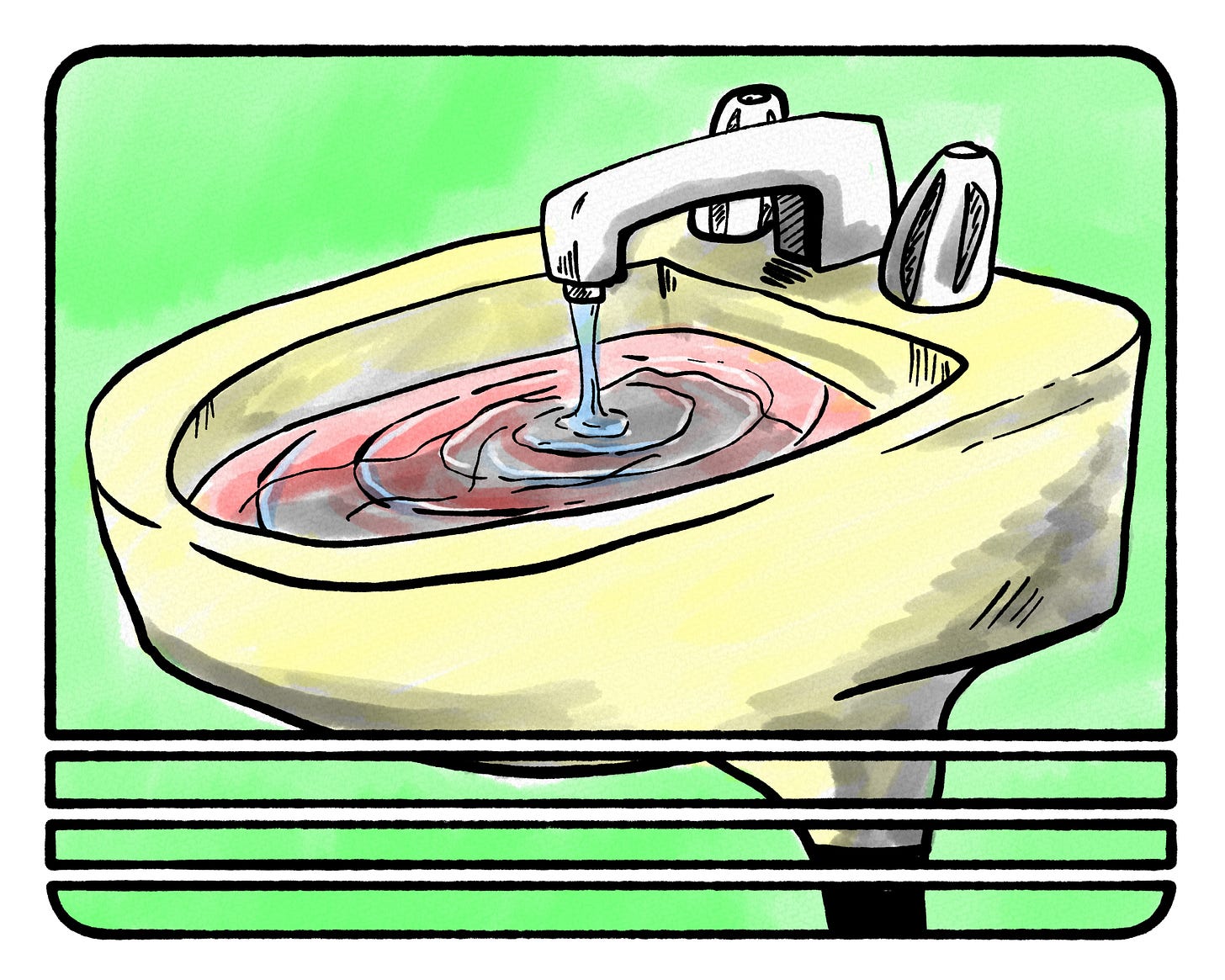

I ducked around the curtain as quietly as possible and saw Gia’s pajama shorts and underwear sitting on the floor, splotched with blood.

“You got your period,” I said like there was any other explanation. “Have you ever gotten it before?”

She shook her head slowly before looking down at her clothes.

Cold disbelief washed over my skin. What a cruel twist of nature that her first period came in the middle of the night at camp.

“You know about periods?” I asked. Gia was twelve, old enough for someone to have told her about menstruation. My fourth-grade Bible study class was my introduction to “Family Life” education, where I learned that bleeding every month from my lady parts was a beautiful gift from God. We learned about puberty on a need-to-know basis, first covering deodorant, breasts, and all the new ways our bodies could grow hair, then graduating to the birds and the bees in sixth grade.

“A little bit,” Gia said. “My mom told me…”

She trailed off and looked down at her legs, where a single drop of blood was trailing down the inside of her calf. Her mouth twitched into a sobbing frown and she leaned down, using the edge of her pink towel to wipe away the blood. Tears made her eyes glint, glasslike in the cheap, buzzy fluorescent light.

“Go get another pair of underwear and new pajamas,” I said gently. She hurried away, fist still gripping the towel. When she’d left, I tossed her clothes into the sink and turned on the cold water just enough so it didn’t make any noise.

As I padded across the cabin floor, Gia silently walked past me and ducked back into the bathroom.

“What are you doing?” Lego mumbled, lying down in her bed but tilting her head over the side so she could see me as I rifled through my stuff, pulling out a handful of pads and a spare pair of underwear.

“Gia got her period,” I whispered, holding up the pads. I glanced around to make sure none of the other girls were stirring; if they were awake, they were good enough at hiding it.

Lego lifted her blanket and swung her bare legs over the edge of the bed. “Let me help,” she said.

“I think I’ve got it,” I responded. It was standard for the senior counselor to handle any camper emergencies, but Gia had come to me.

Lego looked at me for a moment before easing back into bed. “Fine,” she said, as if it made no difference to her.

Back in the bathroom, I turned off the tap and sat on the cold floor.

“Here’s how you put on a pad,” I said, sliding my own pair of underwear over my legs so it came to my knees. I wordlessly peeled open the wrapped, showed Gia how to pull it away from the plastic and affix it to the crotch of my underwear.

“Put it right in the middle,” I said, pointing to my underwear. “That way, the blood won’t leak out either end.”

She tried to readjust her pad, but the sticky side folded in on itself. She unwrapped another pad and got it right on her second try. I turned around while she got dressed.

“What do I do with those?” she asked, motioning to the clothes in the sink. The water had tinted pink, starkly contrasting against the white bowl.

I showed her how to get blood out of cotton. How to soak it so the stain didn’t have time to set, how to run it under cold water and stretch the fabric so the stain drained away, the water eventually running clear.

As we were wringing out her clothes, Gia asked quietly, “Sparky, am I going to have a baby now?”

“What do you mean?”

Gia looked down at the sink. “Now that I’m a woman, when does my baby come?”

“Has your mom talked to you about babies?”

Gia shook her head. I’d gotten the vibe over the week that Gia came from one of those evangelical abstinence-only families; a lot of our campers had that background in common.

“But she told you about periods.”

“All she said was that it’s when I become a woman and my body telling me that it’s ready for babies.”

Gia wasn’t a woman; she was a scared twelve-year-old kid. Maybe in medieval England she’d be considered more mature, but I’d always thought it was unfair of girls to get their period before they were mentally and physically ready to have a baby. “You can still be a kid and have your period.”

“How does that work?”

“Your body makes a bunch of blood just in case it does have a baby. And when there isn’t a baby, like right now, it gets rid of all that blood. That’s what your period is.”

She put a hand over her belly button, brow furrowed in concentration. “So why isn’t it a baby?”

“Well, it takes two people to make a baby.”

“A man and a woman.”

I opened my mouth, but words didn’t come. I didn’t want to do the whole when a man and woman love each other very much bit, because love wasn’t required to make a baby. And two people could love each other very much without the ability to make a baby.

“Two people with different body parts can make a baby. It’s like puzzle pieces: one fits into the other.”

Gia’s face morphed into subtle disgust. “So if I want to have a baby, somebody needs to put their body part inside of me.”

I nodded. “But you’re way too young to do that. Way too young.”

“How old will I be when that happens?”

What was I supposed to say to that? The last thing I wanted was to contribute to this girl’s trademark Christian guilt about sex and orgasms and waiting until marriage. I remembered having this talk with my mom, who emphasized that sex was between a man and a woman and only after they love each other very, very much, so much that they wanted to raise a baby together and be a part of each other’s lives in this world and the next.

But did sex have to be any of those things?

“You’ll be older than you are now,” I said, settling on a safe answer. “And you can only have sex when both people want to. That’s an important part. Sometimes people wait until they’re married.”

“Do I have to do that? Wait until I’m married?”

I started to pick at one of my cuticles as my brain rattled in my skull, trying to shake up an answer. I hadn’t waited; at Kaylee Walton’s bonfire on the last day of junior year, I’d snuck up to one of the guest rooms with Greyson Pickler, a cute guy from my grade who I’d been talking to on and off for the past few months. When he pulled a condom out of his wallet, I didn’t stop him. I wasn’t entirely aware of the concept of finishing, so when he did and I didn’t, he left to go back down to the party. I laid on the rumpled bed, staring at the popcorn ceiling, thinking.

When I rejoined the party, I did a shot of tequila that grated down my throat and I joined the impromptu dance floor, which was a trampled patch of grass in the middle of the backyard. The last thing I remember was looking around the mass of bodies around me, then glancing over at a girl I didn’t know, I think she was from another high school, and thinking that she looked beautiful all glistening and sweaty, her red hair sticking to her shoulders as she moved. I woke up the next morning in my room with a raging UTI.

“You don’t have to wait,” I said. “But you should probably be over eighteen.” That seemed like a safe enough answer. Gia was a sweet kid; her first time shouldn’t be with some handsy seventeen-year-old in a guest room that wasn’t hers.

Lego poked her head into the bathroom. “Time for big zip,” she whispered, rubbing one of her eyes as if she’d been sleeping.

The last thing I wanted was to contribute to this girl’s trademark Christian guilt about sex and orgasms and waiting until marriage.

On the hike out to the big zip, I tailed behind the group to make sure none of the girls got lost in the dark. Gia stayed a few steps ahead of me the whole hike, barely an arm’s reach away. Every few minutes, she’d glance around to make sure no one was looking before picking a wedgie or pulling on the fronts of her shorts to adjust her pad. I pretended not to notice.

The high ropes team who’d be managing the zip was already there, two older counselors who’d outgrown working with the kids and mainly hung out in the big house. Cowboy was a kindergarten teacher who spent her summers at camp to make extra cash, and Echo was Paul the camp leader’s nephew.

The girls huddled and whispered as we stood below the platform, probably talking about how tall it was and how scary it looked. If I stared closely, I could see the supports swaying in the cool midnight wind. The movement was a sign of structural integrity, but the places where you stood weren’t supposed to shake beneath your feet.

Echo and Cowboy laid out harnesses for each of the girls in a semi-circle so they could watch how to put it on themselves. Once all of our harnesses were on, Lego and I went around to each girl to help them tighten the straps.

“Need help?” Lego asked once the girls were tightened up and ushered over to the belay line. She motioned toward my crotch, and I forgot that it was the harness she was really referring to.

“Sure,” I said, pulling up on the waist and thigh loops so it was in place. Lego placed a soft palm on my waist for leverage and took the end of each strap in her fist, yanking hard and strong with her fists. The tightness was uncomfortable on the ground, like all the softness in my body was being squeezed out of place.

I didn’t know where to look as she kept pulling tighter and tighter, didn’t know where to put my hands. Lego scrunched up her nose as she adjusted her nimble fingers to work the loops into place, the pads of her fingers brushing the soft skin of my stomach. Her cuticles were picked-at, her fair-skinned fingers rough with callouses.

“All done,” she said with a satisfied clap before stepping back and adjusting her own harness, pulling on her own straps.

We rejoined the group as Echo and Cowboy were explaining how the big zip worked: the group would hook into the belay line and the person going up to the top would hook into the other end. Using the pulley at the top of the platform, the group would walk backwards and haul the zipliner up to the platform.

When Cowboy explained that they, the girls, would be in charge of making sure they got the zipliner up to the platform, their eyes went wide.

Layla shot her hand into the sky, but started talking anyway. “So we’re getting them up there?”

“Yup,” said Echo, fiddling with a helmet before strapping it onto his head. “Starting with me and Cowboy.”

The first person on belay was the scariest as a camper. But once the girls saw how easy it was to haul someone up to the platform, they would relax. In reality, the ground would have to split open beneath their feet for something bad to happen: as long as they all kept their footing and evenly distributed the weight, they’d be fine.

None of the girls volunteered to go first, so Lego did. She hooked into the end of the line down yonder and the rest of the group hauled her up to the platform. As she zipped down the line, she hollered out, but was too far away and too cloaked in darkness for us to hear what she said.

*

The girls had reunited with their parents and scattered in their separate directions on Friday morning. Lego and I walked back up to the cabin for the last time. She dragged her plastic drawers out from under the bed, hid her container of laundry detergent in a canvas bag underneath a couple t-shirts. Her next assignment was in one of the cabins across camp, so she left to drive her car up from the staff parking lot, making the move a little easier. She’d already loaded everything up and I was barely halfway done with my packing.

“See you around, Sparky,” she said with a quick wave as she headed for the door.

“Wait,” I called. “Can I ask you something?”

She shrugged. “Yeah?”

“Why’d you name me Sparky?”

She went quiet, hands buried in her pockets. “I got to be honest with you, I don’t remember.”

I deflated a little, but tried not to show it.

“Do you like the name?” she asked, raising one eyebrow.

“It’s all right,” I said, drumming my fingers on my mattress. “But it doesn’t really feel like mine.”

“So pick a new one,” Lego said, one hand on the doorframe.

“Can I do that?”

“Probably not,” she said, “but if you could, what would you pick?”

“I don’t know,” I said, looking down at my knees. “My mom calls my little brother Kiwi because his hair was fuzzy like a kiwi when he was born. I always wanted a nickname like that.”

“What’s that line from Romeo and Juliet about names? A rose by another name? Ooh,” she said snapping her fingers. “What about Rosie?”

Rosie was a real name, not a nickname. But I didn’t say that, just nodded and offered a half-smile. “That’s not bad.”

Lego smiled, satisfied. “See you around, Rosie.”

STORY:

Annie Earnshaw is a writer and editor from Charlotte, NC. She has a BA in English from Elon University, where she wrote a short story collection entitled Six Ways to Say I Love You (2021). Annie’s work has been featured in Allure, Carolina Muse, The Merrimack Review, and Alchemy. She also writes Hello Heroine, a (sometimes) weekly lifestyle newsletter.

*

ART:

John Elizabeth Stintzi (they/she) is an award winning novelist, poet, editor, and cartoonist. JES is the author of the novels My Volcano and Vanishing Monuments, the poetry collection Junebat, and is currently at work illustrating their comic Automaton Deactivation Bureau.

Next Tuesday, we’ll feature an interview with Annie about this story!