High Slopes by Jim Kourlas

"These men are desperate, suffering from a peculiar affliction threatening to obliterate their careers: in the face of their terrifying, imagined futures, they’ve forgotten how to remember."

I’ve written in my last few story introductions about voice. This has probably always been true, but these first ~6 months of SSL stories have reminded me just how much I’m drawn to a unique, strong, confident voice in a story. One that immediately grabs you and lets you know the author is in control; one that immediately pulls you into the world of the story.

And that—the world of a story—is another common denominator among these stories, and one Jim Kourlas’ “High Slopes” especially excels at. The world in this story is both familiar and odd, surprising and almost a little upsetting, in a way that I find to be something of a magic trick. It’s a joy to read, and to experience, and I hope you all enjoy.

—Aaron Burch

The shy man arrives at High Slopes Retreat with malice in his eyes. Like most men attending our retreat, he dons business attire: chinos, jacket, no tie. Some wear polo knits embroidered with their company logos. Many wear name tags, though we don’t provide them at High Slopes; they’ve brought their own, out of habit and a fundamental misunderstanding about our aims here. One or two graying gentlemen still wear a suit, blurring the boundary between trade show and funeral. In our lobby, the shy man pretends to talk on his iPhone while those about him shake hands greedily, eagerness on their breaths. They’ve flown into Denver International Airport and driven Hertzes and Nationals up the front range to our retreat hoping to change their lives. That is, after all, what we promise in our brochures scattered about the waiting rooms of psychiatric and wellness offices across the country. The brochures broadcast our logo, a circle resting at the base of an inverted triangle. But we find word of mouth to be the best marketing of all. On putting greens and over ribeye dinners, brokers and executives persuade others to pay our substantial fee and book their flights. These men are desperate, suffering from a peculiar affliction threatening to obliterate their careers: in the face of their terrifying, imagined futures, they’ve forgotten how to remember. The shy man is no exception.

The men are seated in Conference Room 3B, where we dim the lights and project onto a massive screen clips from the 1984 martial arts drama The Karate Kid. The wax-on, wax-off scenes of The Karate Kid bathe the men in nostalgia—a far cry from memory, but a start. It also suggests a non-traditional curriculum is afoot and allows them to project themselves as heroes in the drama we are about to unfold. Some identify with Daniel LaRusso while others Johnny Lawrence. It doesn’t matter which, for all of the men are competitors eager to consume their colleagues, even the shy man. One might even say especially the shy man. By the end of the weekend there will be several instances of cannibalism. There always is.

Once Pat Morita’s lessons have ended, when all of the attendees are surmising what exactly Pat Morita did for a living to acquire such a fantastic home and lot full of vintage cars, when their minds have regressed to ROI and corporate structuring and offshore tax schemes, the screen goes dead and they are shuffled down a long, unlit hallway. All the Exit signs have been disconnected. Nervous snickers punch the darkness. With our night vision cameras and bodily sensors we see the shy man in the rear, not so lost in this darkness, feeling a similar comfort as when he closes his eyes at his desk or steals a moment to console his insecurities in the soft blank void of the supply closet at work. The shy man may be a minority among these extroverted colleagues, but we afford him no special consideration. No one may be comforted if true memories are going to arise.

The scent of chlorine tells the throng they’ve reached the indoor pool, which like the hallway remains pitch dark. It takes little time for those in front to lose their footing and plunge into the water. Their chatter turns to anger, for ruined are their expensive phones, velvety billfolds, designer jackets, and prized cigars. Blind efforts to extract those men ensure that all will fall, for the pool is twelve feet deep, clad in polished Italian marble, and devoid of ladders. At High Slopes, we ensure everyone is equally debased.

The optimists, citing motivational tomes, soon warm to their losses. In every misfortune lies an opportunity, they tell themselves, and they’ve paid good money for this retreat. Like any other management scheme, they must trust the process. So like boys, or how they believe boys would act in such a situation, they begin to horse around, splashing one another. Many have sons, after all. At their country clubs, or on all-inclusive beaches, from the safety of deck chairs, lathered in sunscreen, holding a drink, they have admired the ease of children’s play, but it is in a language now foreign to them, obliterated by work and narratives from entertainment and advertising. And yet here they try to play.

One by one, shoes are expelled from the water and sodden clothing slaps the concrete lip of the pool. We don’t intervene until all of our attendees are completely naked, bodies orbiting one another like nervous planets, their touches met with apologies. Because our company is financed by a certain unnamed royal family, our resources are flush, and our pool drains quickly on command. When the lights finally turn on, the men find themselves shivering in the empty pool, captured by twelve-foot walls of marble polished too slick to grip. In order to escape, they must touch each other, and not in the ways they are accustomed, with joking slaps or competitive handshakes, but more tender and considerate. It’s this initial, tenuous touching—feet laid into interlocking fingers, hands pressed to thighs and buttocks lifting colleagues threatening to tip—that plants the seed of memory.

One attendee invariably remains on the pool bottom. Today he is the shy man, and the overhead lights are excruciating to him. He hides his nakedness with two hands as if his penis were a blasphemy. The men above him shout encouragement, but there he stands, frozen. In junior high, perhaps, the men above might have abandoned the shy one, but they are more enlightened now. Softened by their recent experience of kind male touch, and recalling their favorite war movies, they conclude that no attendee may be left behind. And so they hatch a plan. The lankiest of the group, a VP of sales for an Elgin, Illinois, firm specializing in consumer packaging solutions, sits down on the edge of the pool and spins around. He commands those nearest him to grip tight his ankles and wiggles his buttocks over the edge of the pool until he hangs there like a human ladder. His long penis sways at him as he reaches his hands to his unfortunate comrade.

The men cheer their teammates on. The ankle-holders sweat with exertion, and more join the cause. The face of the man suspended upside-down flushes purple with blood. The shy man, his self-worth blooming, feels himself a worthy member of the team despite his inherent awkwardness and inclination for solitude. He grasps his savior’s hand and with all his might, as if discovering a physical prowess he never knew he had, climbs. The operation requires levels of bodily touch that flood him with anxiety, but cheered on, he proceeds past his savior’s swaying member. His fear that he will mount the pool with an erection is met with the reality that he indeed mounts the pool with an erection, one he cannot hide from the other attendees. He is not gay, he doesn’t think. He has a Kia and a live-in girlfriend of eleven years and two cats named Bart and Lisa. He works in the accounting department for a Pittsburgh engineering firm, and hates how his job brands him as a certain type of uptight person, which he knows he is—but still. He likes boundaries is all, and this experience escaping the pool bottom has obliterated them, as it is meant to do.

His colleagues ignore his erection as if it were a normal side effect of battle, something Spartan or Trojan perhaps, and gather up the Elgin VP from the pool edge. The shy man wants to explain to them it wasn’t the long, fit body of the man who assisted him that triggered his erection but the air that clothed his nakedness. He hasn’t been publicly naked since childhood, he assumes, and the experience has awakened something crucial to his being. It seems his memories have been confined by his stooping and skulking body. As he melts into the group, skinny and ashamed, his erection deflates, and with it comes a familiar disappointment, as if he’s awoken from a very pleasant, very important dream that he will never recall. He feels he’s been denied a seminal coming of age moment like Ralph Macchio’s character in The Karate Kid, and wishes he could crane-kick someone now to set himself free. But he also knows the opportunity to do so passed in junior high, surrounded by pretty girls resembling Elisabeth Shue who found other brave boys to cheer on. He wonders if what seems like an absence of a memory is in fact a bitter memory of inaction, hesitation, and deferral.

He might weep but is afraid of being punched.

He feels he’s been denied a seminal coming of age moment like Ralph Macchio’s character in The Karate Kid, and wishes he could crane-kick someone now to set himself free.

Our Rocky Mountain retreat is secluded by high slopes—hence the name—and only the indifferent fauna is likely to glimpse the men in their nakedness, so the attendees storm en masse like primitives through an open glass doorway into a gorge crowded by lodgepole pine, spruce, and aspen. The stony ground digs painfully into their bare feet but their laughter nevertheless returns, though not as richly as before as many are accustomed to dining well and, following their exertions in the pool area, expect a meal. We provide none. The type of men who seek out our retreat possess a surplus of fat to fuel them through the weekend. Water, however, is necessary in this dry altitude, which is why we have left the men tin cups of an old, nostalgic design for them to carry through the woods in search of water to quench their thirst.

By this late hour, the sunshine has been clipped by the surrounding cliffs and only an ambient glow lights the attendees’ way. Twilight plays tricks on their eyes, causing them to see enemies in the shadows: bears and mountain lions, colleagues and wives and whining, spoiled children. It is not difficult to find water, as they need only listen for the stream that trickles alongside the long gravel driveway that leads to High Slopes. This is not cattle country, so they may drink freely without fear of bacterial infection, though the water tastes alkaline and smells sulfuric. Some spit it out. Others splash it on their necks and arms, imitating the showers they take at gyms following strenuous workouts.

The shy man drinks greedily from the stream. He is cold now, his penis and testicles burrowing into his groin as if in shame. He compares his body to those around him, noting hairy backs and slumps of fat spilling over withered and graying genitalia. But even their portliness seems a sign of vigor. He massages his meager paunch which provides no shelter for his penis, now packed tightly as a buckled accordion. When no one is looking he faces the forest and gives it a tug, trying to warm it and free it from its shyness, but one of his companions, a lawyer from Des Moines, misinterprets his gesture as urination, and sidles up next to him. The man exhales long and loud as he releases an effortless stream that paddles the pine needle floor. He talks about the rescue in the pool, congratulating the shy man on his escape. The shy man is too agitated to urinate while this man’s torrent splashes his feet. He is not strong, but the deep muscles of anxiety clamp down on his urethra and it feels as if he will never piss again. He shakes his penis like he has finished, as if stray drips might darken his nonexistent khakis, finishing the act with a habitual zipping motion. As he turns, however, the lawyer grips the shy man’s shoulder.

This touch is firm and insistent, driving the shy man’s feet into the urine-damp ground. Due to the chatter of the nearby men debating the water quality and their next plan of action, and a technical glitch in our digital feed, it is impossible for us to hear what the two men say to one another, but we are pleased to at least witness the shy man meeting the lawyer’s gaze. The lawyer wears an unctuous smile, so we assume he is propositioning the shy man, who steadfastly refuses his advances. The lawyer’s penis grows larger as he strokes it with his left hand, his right one now grasping the shy man’s nape as if he were a boy in trouble. The shy man squirms from his grip and slips to the forest floor, where he grasps a chunk of granite. He rises and strikes the lawyer square on his crown, an oval of receding hair providing a perfect target.

The lawyer is not dead, only bloodied and woozy as he stumbles across the ground, searching habitually for reading glasses he was not wearing and a fountain pen he did not drop. Their colleagues witness the act of brutality and are split in judgment, some siding with the lawyer and others the shy man. Some hike back to High Slopes to seek authority, only to find our sliding doors securely locked, the lights off, and no indication that the building is in fact a functioning resort at all. Others attempt to organize. One of them, a logistics engineer from Memphis not well-versed in the natural sciences, looks about for a conch shell, though he can’t remember why.

The problem for these men is that they all deem themselves leaders. They have all attended the requisite leadership conferences to advance their careers but employ conflicting methodologies for commanding teams. As such, with night falling and a chill setting in, factions form. Groups of men siphon off from one another. They huddle together for warmth, mindful of each other’s boundaries for fear of the same fate befalling them as did the lawyer from Des Moines. Their voices spar in anger, but they throw no fists, deciding the aim of the retreat to be an endurance test. Our night vision cameras record the men nodding off, one by one, leaning against each other or curled on their sides, shivering, wrists crossed in their crotches for warmth. A few, however, split off from the others and remain awake through the night, whispering negotiations as if they were merging Fortune 100 companies or fixing commodity prices.

The shy man, strangely enough, is among this latter group. His anxiety has made it impossible to sleep, and though he is not explicitly welcome in the negotiations, the attrition of the others deputizes him. They joke that he is their enforcer. He warms to this idea. In fact, this idea is the only thing keeping him warm throughout the night, since his companions, assuming he is an unstable homophobe, are rightfully hesitant to touch him. When dawn finally crests the treetops, the self-appointed leaders rise to wake their companions. They hand the shy man a rock to wield. It is a joke but not a joke, and for a moment he considers the nature of jokes, his own life being something of a joke, all of their lives jokes, and in his fatigue erupts into snorts and giggles.

His laughter is not met in kind. His companions on the forest floor snarl with the absence of familiar comforts. Still, he laughs. Perhaps he’s only tired, ready to sleep now that it is time to seize the day, or perhaps he has recognized correctly the nature of our retreat as a joke with no punch line, only setup after setup that carries on forever and ever like an impossibly complex dream. The heft of the rock unhinges his elbow, so he pitches it underhand into the forest, delighting as a delirious man might in its arc through the air, the snap of the branches and the final, satisfying thud. He thinks he is finally making an impact.

The problem for these men is that they all deem themselves leaders. They have all attended the requisite leadership conferences to advance their careers but employ conflicting methodologies for commanding teams.

The shy man does not realize the rock landed on a software developer from Austin. This other man startles awake, calling out for his ex-wife Courtney, who we know left him for a radiologist the year before. While other men grunt and stretch, their tongues parched and sour, the developer has a vision, a memory in fact. We will discover it later, but for now we can assume it goes something like this: he remembers the way Courtney would sweep her long auburn hair over her left shoulder whenever she bent to spit her toothpaste in the bathroom sink. He remembers the way she rose up then and dabbed her lips with a hand towel, and the always three snaps of her toothbrush against the sink rim before she dropped the brush in the aluminum carousel they bought together at Target. He remembers placing their twin brushes in it for the first time, one lime and one blue, and imagining two more completing the quartet someday, shorter ones branded with R2D2 or Elmo. He remembers arguments then, and the once-shiny carousel splattered with Crest. Then he whimpers and trudges off into the wilderness to recall more such memories in peace, safely connecting the deepest recesses of his past, and I, armed with a bathrobe and slippers and a voucher to a nearby spa, retrieve him.

While the self-appointed leaders some distance away present to their yawning brethren the plan they’ve formulated to storm the High Slopes Resort and take it like a woman, the shy man witnesses the software developer slouch away. He follows his target from a safe distance, mistaking the man’s sniffles and wails for those caused by the rock he threw. The shy man is struck by remorse and wishes to apologize, fearing something of the extroverted men at this retreat has rubbed off on him, or awakened inside him, and it is fundamentally distasteful, because he has never considered himself like them. In fact, he has always considered himself the very opposite. But here in the naked morning he senses something about opposites that troubles him.

Though he’s lost the ability to remember, he knows for certain what obliterated his memory in the first place: his fixation with the power of others and his own corresponding lack of it. It was this simmering frustration that carried him quietly through his professional life, riding the coattails of more assertive leaders while he accrued a modest amount of deferred wealth in his retirement account. But it has reduced his memory to a collective history written by others—a rote tally of wins and losses in which he can only claim the latter. To combat these feelings, he imagines himself rejoining the men of High Slopes, leading them in their charge against the retreat, smashing into the building with rocks and branches to find its leaders, dismember them, and declare himself victor. He wants to. And here in our corporate wilderness, this admission shames him. So instead of action, he stands like a tree, hoping his past might return like a gust of wind. He stands and waits, but this only reminds him of his own tendency toward paralysis and inaction. He is at an utter loss. In other words, he once again has lost.

You may wonder why the software developer’s memory returned. Was it the pain the shy man inflicted upon him? Was it his relegation to the role of an innocent? No. At the risk of disclosing proprietary secrets, we’ll pause the footage and data stream at the precise moment the software developer awoke. To the untrained eye it is impossible to detect, but our research has found that on the precipice of waking and sleeping, not just memory is inaccessible, but identity itself. The software developer couldn’t remember who he was, his name or credentials, his home or date of birth. Naked in the woods, he was open to the woods. The air was in him and out of him, clothing his nakedness in silence. And because he was no one and had nothing to manage and therefore nothing to hide, true memory emerged, and it was full of pain, regret, and humility, as all memory must be.

Many shy men have passed through our doors hoping the retrieval of their memory will absolve them of their shyness. But they cannot remember the precise details of their undoing. I know this because I, founder and CEO of HiSlo, Inc., a South Dakota corporation, am a shy man myself and occupy a unique vantage point to observe these men of our time. Rather than hiding behind a wall of screens, ordering my team into action, I spend hours in the field. And these are my findings.

Inside all men, a shy man resides with malice in his eyes. This shy man goes about his life as cursed as Cain, the first of all shy men. But Cain was not a man of inaction, if you recall, and remembering his dark, disappointing past will not make him as innocent as Abel. There is no innocence in remembering, after all. Memory is simply an ever-evolving story casting ourselves as heroes in our own life dramas. These attendees of High Slopes who have replaced their memories with conventional recitations of financial outlooks and marketing schemes feel that they are no longer heroes, and this disheartens them. The shy man inside them has risen to the surface, threatening to overtake them with loneliness and terror. And what else do can these businessmen do but consume him?

As I ferry the software developer away by ATV, I can hear the shy man calling after us, imploring us to wait, but I ignore him. His colleagues in the woods are hungry now, and must be fed.

STORY:

Jim Kourlas earned an MFA degree in fiction from Roosevelt University and has stories in Longleaf Review, HAD, Hunger Mountain, Lost Balloon, and elsewhere. He lives in Omaha with his family.

*

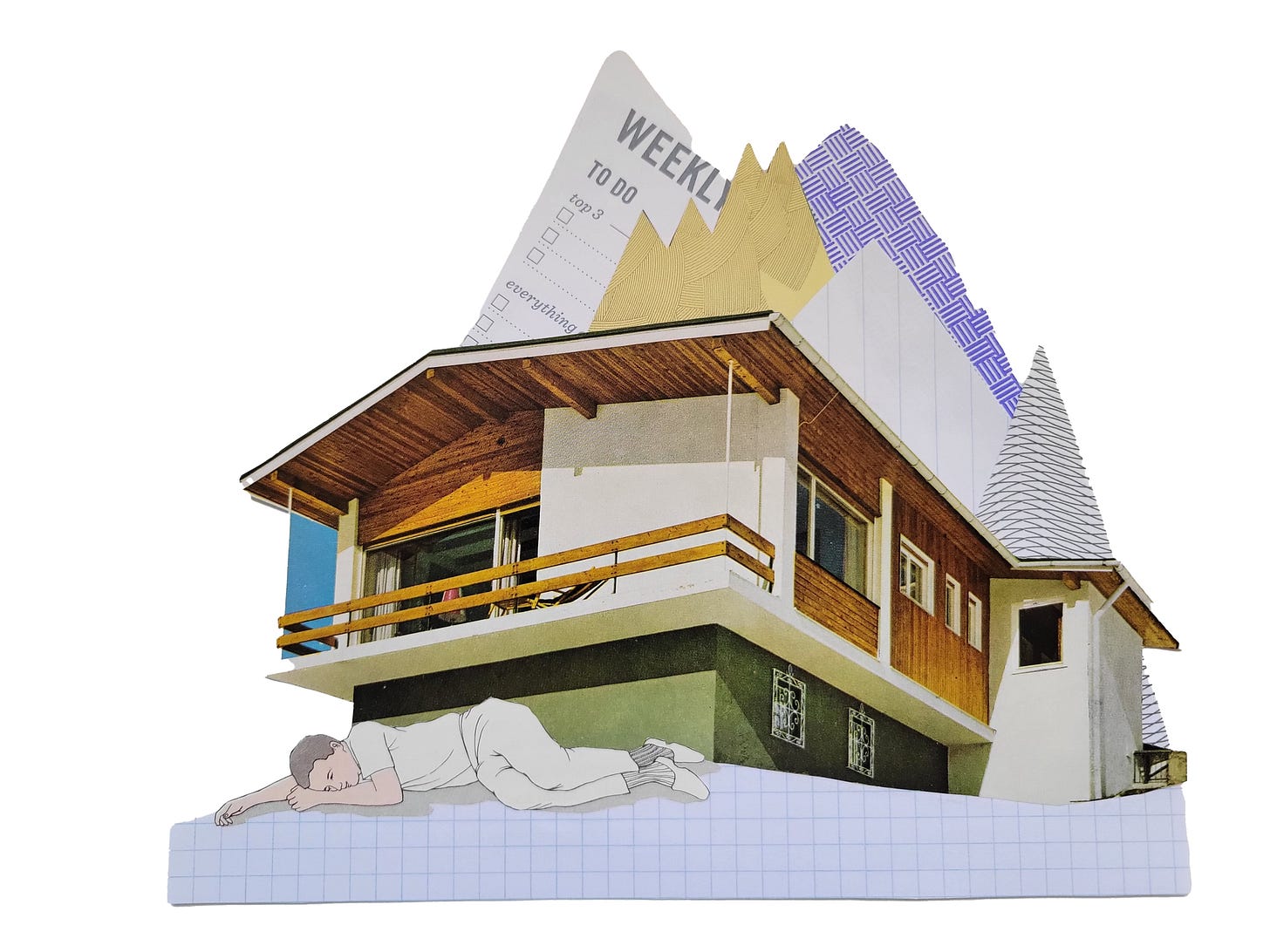

ART:

Meghan Phillips is a writer and collage artist from Pennsylvania. You can find her writing at meghan-phillips.com and her collages on Instagram at @mcarphil.

Next Tuesday, we’ll feature an interview with Jim about this story!