Female Anatomy by Lindsay Hunter

"She wanted to disarm him, show him that she wasn’t a bad person, hadn’t been doing anything wrong, didn’t deserve the rage she plainly saw in his face. What did he want from her?"

Lindsay Hunter is one of my favorite writers. If you haven’t already checked it out, I can’t recommend her novel, Hot Springs Drive, highly enough. It was possibly my favorite novel last year, and you can even listen to us chat on the Lives of Writers pod, if so inclined.

This might be the longest story I’ve ever read from Hunter, and it’s a knockout. So much of the voice and energy that is present in all her work, while feeling like it is making some new discoveries along the way. I’ve read it a few times, and it feels like it surprises me anew on every read, each time fully sucking me into its world as to feel wholly consuming. I couldn’t be more excited to get to feature Hunter here on SSL and I hope you all find yourselves similarly stunned and in awe.

—Aaron Burch

Listen to Lindsay read the story:

Then

Spring had come. The air still held a bite but there was a softness that chased it, a sweetness Alma could taste. Yesterday had been a short gray smear bookended with freezing darkness, but now, today, as the afternoon blended with evening, the sky was creamy yellow at the horizon and the sun promised warmth, more and more each day. Alma unzipped her coat and let in the pleasant air, bent to unleash her dog, Buckley. Off he streaked, his golden fur shimmering in the waning light, and chased a squirrel up a tree. Even his barks landed softly, just another sound in the changing air. A mother pushing a stroller knelt to point at Buckley. Her child watched with two fingers in his mouth and made emphatic Mm noises. A small white dog raced over, barking first at the tree and then at Buckley. Alma waved at the little dog’s owner, a man in a worn green tracksuit with a face reminiscent of an otter. If they had been closer, she’d have commented on the day, how the seasons dropped in without warning, how nice it felt to let the breeze touch her skin. But Alma wanted to do the trail with Buckley before it got dark, wanted to take her time and come out before the lampposts flickered on. She whistled and Buckley trotted over and together they walked between the two cedar trees marking the trail entrance.

Just inside the wooded area, the trail turned sharply left, so that it felt as though the park had disappeared, was miles away. Alma and Buckley were completely alone, enshrouded by trees, very far away from her slow laptop, her wobbly desk. She swung her arms, took long strides. The smells were returning, too, she noted. Melting snow and wet dirt and something deeper, something green, an herbaceous funk that promised grass and blooms and heat. Buckley ran from tree to tree, lifting his leg, shoveling his nose under leaf piles. Mud coated his paws and halfway up his legs, and it would be a pain to clean, but he was so happy, so free.

Above them the sky was a pale weathered scrap, ragged at its edges from the spruce and cypress. It changed shape as the trail turned. Alma had two strips of bacon wrapped tightly and sealed inside a plastic baggie, a surprise for Buckley that she’d give him once they reached the clearing at the center of the trails. He bounded ahead and she couldn’t see him until she made a turn, then he’d disappear around another bend. She could hear the small white dog still barking, its shrill little yips insistent, rhythmic. The world was right there, still just right there.

The shoelace on her right boot was coming undone, and Alma knelt to tie it, the ground cold and wet under her knee. Buckley had run ahead again. It felt good, amazing, to allow her dog to run free, to grant this small measure of wildness. Alma stood, relishing the feeling of stretching her legs. She breathed deeply, catching a new scent. Nearby, something rotted.

She continued, hurrying toward the clearing, her hand searching her pocket for the bacon. But there was something different. A shift, a change. The feeling she got when she realized she’d forgotten something but didn’t yet remember what it was.

It was quiet. That’s what it was. The white dog wasn’t barking, the breeze had stopped, and the trees were no longer sighing. And Buckley. Alma couldn’t hear him crashing down the trail, or stopping and panting, or huffing his nose over the muddy ground.

“Buckley,” she called. She listened, waiting to hear him rushing back to her. When he didn’t, she began walking quickly. He knew about the bacon. It was part of their routine. He was probably waiting in the clearing, sitting and staring at where he knew she’d emerge.

Around the next bend, a man was bent over her dog, Buckley’s collar tight in his fist. “It’s okay,” Alma called. “He’s mine.” The man straightened and she could see his face, the red cheeks and the patches of stubble. He was tall and broad and wore the kinds of boots Alma’s father called shitkickers. Alma stood across from them, her dog held fast by this man. His hair looked oily at the roots and hung limply at the sides of his face and neck. He looked cold, or too hot. “That’s just Buckley,” Alma tried again. She held her hand out and Buckley strained toward her but the man didn’t release his grip.

“It’s off leash,” the man said. His voice was pinched, whiny. Alma let a rush of assumptions wash over her: he was undereducated, he hated women, he was quick to anger when driving on the highway. She pictured his room: bare walls, a thin mattress, a clunky desktop PC on a card table, showing porn.

Alma raised Buckley’s leash. “Here it is,” she said. “It’s okay for dogs to be off leash in the trails.” She wasn’t sure if this was technically true, but everyone did it. She thought of the white dog, also off-leash, of countless other dogs who ran free, knocking into picnics and families. The park had a dog-friendly reputation.

Alma moved toward Buckley, clipped his collar to the leash. She was close to the man now, too close, could smell his sour t-shirt and see his thick, yellow teeth. “Could you let go now?” Alma said. She tried to laugh a little, allow some space for it to turn into one big misunderstanding, just a run-of-the-mill awkward interaction. The man let go and Buckley rushed behind Alma, wrapping the leash halfway around her legs. “I think you scared him,” Alma said. The leash thrummed with Buckley’s shivers. “He’s just a big baby.” She wanted to unwind herself, move into the clearing, but she’d have to walk past the man, who still stood there, watching.

“I’m Alma,” she said. She wanted to disarm him, show him that she wasn’t a bad person, hadn’t been doing anything wrong, didn’t deserve the rage she plainly saw in his face. What did he want from her? “Sorry if Buckley scared you,” she said. Still the man stared. “We’re just happy to be out in this weather.” She looked up, expecting the pale sky, but the night was already layering in, deepening it to blue. Hadn’t it been only a few minutes? The man must have brought the darkness with him, Alma thought. She tried not to feel the alarm that clanged through her.

“Actually,” she said, “we’d better get back.” She started to turn. Buckley lurched, pulling the leash taut, and Alma tumbled to the ground. “Shit,” she said. Buckley disappeared around the bend, the leash dragging behind him. He’d be back out in the park before she could catch him. She’d have to run. But the man was holding her arm.

“Please don’t touch me,” Alma said. At work, in relationships, she hated confrontation, but she’d learned over the years to speak as plainly as possible. The man tightened his grip, pulled her closer. It was then that Alma saw, over his shoulder, a woman halfway down the path. She shook her head at Alma.

“Who is that?” Alma asked.

The man didn’t look. He already knew she was back there. Alma tried to see her again, could only see glimpses: she had red hair, she looked sturdy, she closed her eyes and wrapped her arms around herself.

“Leash your fuckin’ dog,” the man said.

Alma yanked her arm away, stepped back. “I can make my own decisions, thank you,” she said.

The woman called to her, said something Alma couldn’t make out.

“What?” Alma said, cupping her ear. She backed slowly toward the bend in the trail. She’d turn and run as soon as she made it there. The woman called out again.

“I can’t hear you,” Alma said. She looked behind her. Almost there. A gust of wind hushed through the trees. When she turned back, the man was holding a gun.

“Leash your dog,” he said.

The woman was closer now. “Just go, honey,” she said. Alma turned and ran.

At work, in relationships, she hated confrontation, but she’d learned over the years to speak as plainly as possible. The man tightened his grip, pulled her closer.

Bursting from the tree line, back into the park, Alma found she couldn’t use her voice. She wanted to call Buckley, already running back to her, dragging his leash. She wanted to yell to the mother with the stroller, the man with the white dog, tell them what had just happened. But her throat had closed, allowing only for small sips of air, her heart pounding as though it were trying to beat down a door. She dropped to her knees. One by one, the streetlights at the edges of the park came on. Buckley licked her face, snuffled her ear. With the lights on, the sky was darker. Alma watched as the mother pushed the stroller out of the far exit. She pushed her hands into the earth, so cold it stung. Slowly, her breath came back to her, and she was able to sink lower, to her elbows, taking long inhales that hurt her lungs. Her body relaxed, her muscles aching.

“Are you having a panic attack?”

Alma looked up to see the white dog’s owner standing over her, holding his pet under his arm like a football. He knelt, placing the dog down, and held his palm flat, level with her face.

“I’m Robert,” he said. “Just watch my hand,” he said. He raised it slowly, then flipped it over and brought it down. Up, then down. Alma felt her breath syncing with the movements.

When she could sit up, when she had enough air, she said, “A man.” She gestured over her shoulder, at the darkening entrance to the trail. “In there.”

Robert looked over her shoulder, then back at her face. “You saw a man in there?”

“A gun,” she said. In her mind it was a black shape, a gun shape, blocky and wrong in all that nature, in that forgiving air. “He pointed a gun at me.”

“Oh, my god,” Robert said. He reached for his dog, then put his hand under Alma’s elbow. “Get up,” he said. When she was on her feet, he said, “We’re walking over there.” He pointed at the far exit, where there was a bus stop. “And then we’ll call the police.”

She wanted to hug him, this stranger who was giving her cover, telling her what to do, who was even holding Buckley’s leash. At the bus stop he pulled out a worn flip-phone, the keypad loud as he pressed the three numbers. Alma sat on the bench, Buckley’s leash wrapped around her hand, and listened as Robert explained the situation. “There’s a lady here with me who just had a gun pulled on her,” he said. He listened, then held the phone against his shirt. “She says to ask you why,” he said.

“Why?”

“Why that maniac pulled out his gun.”

Alma didn’t know how to answer, could feel her face slackening into a gape. “I had my dog off leash,” she said.

“Jesus,” Robert said, then held the phone to his ear and repeated what she’d said. He nodded, hitched his dog higher on his hip. Then he snapped the phone closed. He sat down next to her, put the dog on his lap. “They said they can’t make this a priority,” he said.

The little white dog sniffed her sleeve, then her hands, then gave her a darting lick. “A priority?”

“They said when the weather gets nice, they get all kinds of calls. Not enough bodies to send out on every call.” He looked past her, then checked his watch. “The bus...” he said. “That was their word, by the way. Bodies.”

Alma stood, tugged Buckley to her side. “I have a car,” she said. She wanted him to offer to walk her to it. It was full dark now, and her car was a long block away, parked as close to the trail as she could get. What had she been thinking, just a short two hours ago? She searched the park, skating her eyes over the trail entrance. It had emptied, and it was still technically winter. She thought of her desk at home, of the bowl and cup she’d left there since lunch, the broth inside the bowl cold now, its murky seasoning settled at the bottom, watery at the top. Every day, the same thing.

“Listen, honey,” Robert said. He scooted closer to where she was standing. “You have to be more careful.”

A car passed, bringing with it a blast of wind that enveloped Alma the way a magician flourishes his cape. "Thank you," she said.

Years Later

Alma’s feet ached. She wanted to sit, but where? She was still holding the matcha latte Jordan had pressed into her hand, though it was cold now, and its little foam penguin face had smeared. Jordan, her boss, who had twice the degrees she had, and a luxury car Alma had never even heard of, was at the point in their meeting in which he was attending to her neck, his hands still above her waist, though after the neck usually came the collarbone, and then the little nuzzles and moans as he moved his face from breast to breast. At that point, his hands would go up her skirt or down her waistband.

“Jordan,” she said. Her arches were pounding. A recent internet search revealed that she likely had plantar fasciitis. She needed more arch support; she needed to do foot stretches; was she taking daily calcium/vitamin D supplements? “Jordan.”

“Shh,” he said. These daily meetings were marked as “Alma check-in" on his calendar. They were a fifteen-minute wedge in a day that started at six a.m. with his personal trainer and ended at ten p.m., when he and his young, pretty, nice, capable wife kissed each other goodnight. This wasn’t something Alma imagined. He often talked about his day, how it was organized and timed to the second. His calendar was the secret to his success. And she was part of it. She was one fifteen-minute section of his day. There was no small amount of pride in that for Alma. She relished heading into his office with an empty file folder, closing the door behind her, snapping the lock into place.

Or, she used to.

He required her to stand still. He’d had a fantasy, ever since he was a child, that a woman would just stand before him and let him touch her. That, yes, she could moan, her breath could quicken, her underwear could grow wet, but she couldn’t ask anything of him. She couldn’t comment or guide. It was his fetish, his kink; he’d been very open about that when he’d first described the fantasy at the office happy hour nearly 17 months ago, when the two of them had closed down the bar.

“I think,” he’d said, squinting at her though they were leaned very close to each other, “I could like you.”

He was nearly a decade younger than her. He had a sweet little family. He was newish at the company and Alma had been there nearly fifteen years. She had a stubborn roll of fat under her bra line that was starting to show up in photos. She’d been flirting for months with a manager in the graphic design department, and had nearly sent him a photo of her naked torso that she’d spent an hour taking in her bathroom, when he asked if she wanted to come to his wedding.

“Oh yeah?” she’d said to Jordan, that night at happy hour. She held back a tequila burp. “I’m pretty likable.”

“Jordan,” she said now.

He stood, slapped his thighs. “What?”

She kicked off her shoes. A chickeny smell rose between them. “Oh god,” he said. “I love your feet.”

She set the latte down on his desk, then picked it up and dropped it into his trash can.

“Fuck,” he said. “Maintenance is going to think I did that.”

“I just need to sit,” Alma said. She took his chair, her back sinking into the plush leather. She opened one of his drawers, found his rubber band ball, and began rolling it under the arch of her foot. “Yes,” she breathed. “Oh, yes.”

He looked at his watch. “I’ve only got six minutes left.” He came around the desk and knelt before her. “Let me just see,” he said, his hand snaking up her thigh.

She stared at the photo of his family, all in jeans and white oxford shirts, the baby with an enormous flower headband perched above her brow. His wife was named Jamie. She was a kindergarten teacher. She had a brother overseas. She was allergic to walnuts. A golden retriever was perched at her feet in the photo, wearing a denim bandana. The dog’s name was Buckley. Where did time go? Alma’s Buckley had died several years back after getting cancer in his front leg. His paws smelled like corn chips, his head like cake mix. His ashes were in an urn patterned with a bright pink lotus flower. Where was that urn?

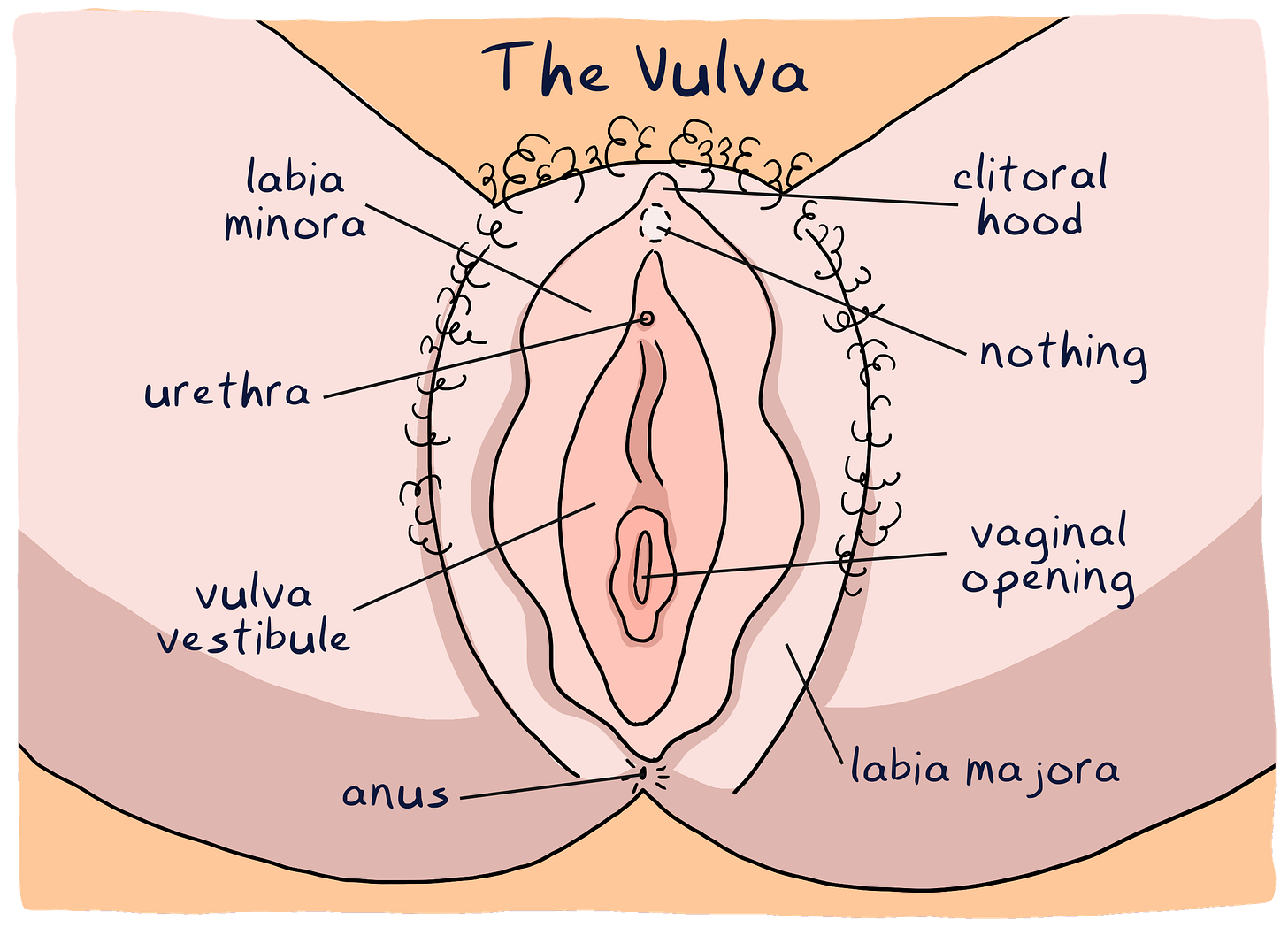

“How come you don’t have a clitoris?” Jordan asked, rubbing his stubble against the inside of her thigh. He looked at her, his eyes moving rapidly. “I’ve always meant to ask.”

“I’m just not in the right mindset,” Alma said, consciously avoiding the phrase not in the mood, a cliché that was, in her estimation, buried under its own baggage. For one thing, mood rarely synced with moment. Alma had learned that all too well.

“I’m not talking about today,” he said. “I’m not talking about right now.” He sat back on his heels, checked his watch again. “Three minutes,” he murmured. “Let me just move against you,” he said, already shifting forward. He rubbed his erection against her shin. His breath smelled like coffee and orange Tic-Tacs. She moved the rubber band ball to the other foot. That he would likely come in his pants never seemed to be an issue for him. They were rushed for time most days; he orgasmed behind his zipper often. “Uh,” he said, and slowed, gripping her tighter. Alma remembered that her shins bruised easily.

She left her shoes but took the rubber band ball with her as she left.

Later that day, Jordan pinged her on the company chat app.

I was sincerely asking

She waited.

I wasn’t trying to make fun of you or anything. I’m nto a jerk

She scanned through their check-in. She couldn’t remember him making a joke.

Is it like something you wre born with, he said.

Or born without I shld say

Then it clicked.

I have a clitoris, she typed. Maybe you need an anatomy textbook! She fought the urge to add an emoji.

No you rly don’t

I'm being serious Al

Trust me I've looked

She switched her status to “Busy” and minimized the chat. She’d had these conversations before, what woman hadn’t? Another man that misunderstood female anatomy. Another man that confused taking with giving.

She was editing the company newsletter. She’d highlighted This month we’re excited to. She added a comment. “Not actually,” she wrote. “We’re not actually excited.”

His breath smelled like coffee and orange Tic-Tacs. She moved the rubber band ball to the other foot. That he would likely come in his pants never seemed to be an issue for him. They were rushed for time most days; he orgasmed behind his zipper often.

Then

Buckley walked just ahead of Alma, turning every so often to look at her. “I’m fine,” she said in the baby voice she’d used when first adopting him. “Mommy’s okay.” She’d read dogs could smell fear, anxiety, sadness. She felt Robert’s presence behind her, growing larger, looming. She wanted to get somewhere he couldn’t see her, even as logically she knew he probably wasn’t looking. He’d seen something in her, something uncareful, something she should work to eliminate so no one else pulled a gun on her. Her heart lurched around her body. She felt it in her head, her neck, her legs.

The tree line was ahead to her left, a furred darkness. She hadn’t noticed the man or the red-haired woman exiting; were they still in there? Did they live there? Was the gun loaded? Why did he pull it out; why, when she had nothing but a leash?

Finally, the car. Buckley leaped into the back and she folded into the driver’s seat. She pushed the button to lock all the doors, pushed it again. If anyone approached, she could honk the horn. She could drive away. She could run them over. Buckley panted in the back, his breath moist and filling the car with an eggy smell. She pulled carefully away from the curb, easing slowly into the furthest lane from the park. Two blocks down, there was an ice cream shop, lit yellow against the gloom, its inside walls a salmony pink. Alma watched a woman at the table by the window carve a spoonful from her cone and lower it to her baby in its stroller. It was the same mother from the park, the one whose child had been so delighted by Buckley. Wasn’t it? Alma leaned over, tried to see better. Behind her came a rapid series of honks. She jumped as if shot.

*

At home, brushing her teeth, the incident felt far away. Buckley was curled up in his nest of old blankets, paws twitching. The TV murmured, a rerun of a show that was popular when Alma was in high school. Had it happened tonight? Or last night? It began, for Alma, to feel silly. Or, more specifically, like something she could rework into a silly story. Something she could drunkenly recount at a dinner party. This redneck pulled a gun on me! Waved it around like I was supposed to be afraid! At this dinner party, Alma had an immaculate short bob. Toned shoulders. Clean, polished nails. Someone was rubbing her back. The fellow guests listened with a complete set of reactions on their faces. There were candles, wine, mirth.

She lay in her bed. She kept the lamp on but dimmed. Above her, the ceiling fan was on its lowest setting. Her eyes kept catching the blade with the nick. She couldn’t stop following it around and around. For the longest time, she tried to let the blades move in a blur above her. Tried to blind herself to the flaw in the shitty manufactured wooden fan blade. She woke in the morning with her fists clenched. A voice, her own voice, sounded in her head. You know, it said. It would be easy to find him.

*

It rained all day in relentless sheets that cascaded down her windows. Buckley whined and refused to go out, then finally peed on the bathroom rug. Alma rolled it up, intending to take it to the laundry room, but the rain. She wedged it into the kitchen trash can and scratched behind Buckley’s ears. “It’s okay, buddy,” she said. “I get it.”

Alma opened her laptop and saw that the project manager on one of her projects had sent edits. “Thank you!” she responded, then batch-accepted the edits, deleted any comments, and posted it to the file sharing site. She opened a fresh document and made a list:

6 feet tall

Dark hair

Dark eyes (?)

Shitkickers

She tried to picture the man’s hands. Was there dirt under his fingernails? Were they calloused?

Dirty nails

Straight teeth but they were yellow

Gun: it was black

She watched the rain, then decided it was late enough in the morning to begin preparing lunch. She rinsed her bowl from the day before and set it on the counter. As she was emptying various packets into it for ramen, she remembered the woman. She rushed back to her laptop.

Red hair

Shorter than him

Didn’t seem afraid of him

Just go, honey. Her voice, insistent but resigned. Like maybe, Alma thought, the man was prone to tantrums. This made Alma feel close to the woman.

The teakettle shrieked and Alma poured hot water over the stiff noodles. She bent her face into the steam, closing her eyes as it bloomed.

Her eyes snapped open. A gun. A gun!

It began, for Alma, to feel silly. Or, more specifically, like something she could rework into a silly story. Something she could drunkenly recount at a dinner party. This redneck pulled a gun on me! Waved it around like I was supposed to be afraid!

The rain stopped in the afternoon. Outside, the world was alive with the sound of water dripping, flowing, draining. The streets looked washed clean as Alma drove to the park. The sun was out but already on its descent. Buckley kept his head out the window.

She was there earlier than the previous day, and owing to the rain the park was empty, glistening in the waning daylight. She pulled Buckley’s leash toward the woods. He dug his paws, tried pulling her to the other side of the park, but eventually he gave in, and they entered the trailhead together.

It was quiet and lush, as though the rain had plumped the trees. The ground squelched underfoot. Alma and Buckley walked quickly, tethered to one another, all the way to the clearing. The picnic tables were empty. Alma listened, turning in a slow circle, trying to see everywhere at once. Her eyes settled on the trash can, overflowing with wrappers and poop bags and fast-food containers. She walked to it and Buckley got excited; she never let him get that close to garbage. He sniffed excitedly. She peered at the contents, wondering if any of them had been touched by the man or the red-haired woman. She’d named them Gun and Hair, she realized. Did Gun eat that Big Mac? Did Hair polish off that Frappuccino? Buckley whimpered and sat, his front paws tapping nervously.

“What did you find?” she asked. She knelt. His paws were near a rolled-up newspaper, one of those kinds that were all coupons and conspiracy theories. It was soggy and began to disintegrate as she unrolled it. There was an address label in the bottom corner.

Lawrence and Susan Nowak. 731 Jericho.

Alma held it to Buckley’s snout and he whimpered again, tried to pull away.

Lawrence and Susan. Gun and Hair.

“Good boy,” she said.

She pulled up the address on her phone. She knew the neighborhood, it turned out. Three neat rows of small boxy homes behind the shopping center where she bought groceries. Of course, she thought. Buckley nudged her hand, her pocket. She’d forgotten the bacon.

That night she dreamed she was swimming. Her hair kept getting in her face. She couldn’t see and she swam right into the open maw of the pool drain and slipped down a rushing waterfall, her butt leading the way. She landed in front of a blond wooden desk, staring at the earnest ankles of the man sitting there. “Be careful!” he hissed.

*

Years Later

Alma’s gynecologist was a small man with an obvious hairpiece who reminded her of Paul Simon. His little hands didn’t frighten her, and he always narrated his actions as he went as though she were his assistant and not the woman he was probing. Speculum, he’d say, just before inserting it. Swab. Alma would nod, assenting, but also in mutual recognition. A project they were completing together. The paper of her gown crinkling cheerfully. She’d always imagined her vagina in those moments as something one would find under a rock, in the dark, cool soil, something eyeless and pulsing and eager to return to darkness. She would shiver for hours after. His name was Dr. Birnbaum.

“I understand you’ve been sexually active?” Birnbaum said, his hand frozen just above his computer mouse.

“Indeed,” she said.

Carefully, he inserted the pointer finger of his other hand under the hairline at his forehead. They both listened to the scritching sound. He sighed and clicked the mouse rapidly, then swiveled to face her.

“Not time for your annual,” he said. His hairpiece was askew and Alma looked baldly at it. He wasn’t the type to care; it was one of his best qualities. That he had a vanity but it had its limits.

“I need you to locate my clitoris,” Alma said, “and then I’ll hand my phone to you and you tell my boss I have one.”

He made a little smile. Everything about him was pocket-sized. “I can’t do that,” he said. He went back to the mouse, began clicking again.

“I’m giving you my consent,” Alma said. She put her hand on his wrist, felt a thrill at its doll bones.

“Even so,” Dr. Birnbaum said. “I find it inappropriate, an over-reach on the part of your boss, a waste of my time, and pointless.” He stood and Alma stifled a giggle at his little leggies.

“Okay,” Alma said. “Then can you just sign something? I’ll type something up on that computer and you sign it. Maybe we can even include coordinates. Is that a thing? Body coordinates? It should be.”

“I can’t do that,” he said, “because number one, we don’t like patients touching our keyboards, and number two, you don’t have one.” He made a show of bending over the keyboard, logging out with a flourish.

“I don’t have what?” Alma said.

“You don’t have a clitoris,” Birnbaum said. He pinched the air in front of him, then let his hands fall to his sides. “You never have. Not as long as I’ve been your gynecologist.”

Jesus Christ, Alma thought. “Jesus Christ,” she said. “Is there a female doctor I can speak with?” She opened the door, leaned into the hallway. “Excuse me,” she said, flagging down a passing nurse. “Could you bring in a woman doctor?”

Birnbaum sighed behind her. “That won’t be necessary,” he called, his voice tired. “Thank you, Theresa.” He put one hand on Alma’s shoulder and used the other to ease the door closed. He sat and gestured for Alma to do the same. Now his tininess felt annoying, like an optical illusion she couldn’t escape.

“You never thought to mention this?” Alma said. Her heart was pounding, her breath escaping her. “I’ve been coming to you since—” Since when? Alma unwound the years. Her insurance at work had changed and so she’d had to find a new doctor, who referred her to Birnbaum, her first gyno. That was the year she went crazy. The year of the gun. Suddenly, she could smell Buckley’s hot breath, like wet food out of the can.

“I thought you knew,” Birnbaum said. He put his chin in his hand and crossed one leg over the other.

She thought of the times Jordan was down there, fumbling around with his fingers and tongue while she waited for him to get bored so the real action could start. She liked it, didn’t she? She looked forward to it. She did. Why did she look forward to it? She liked Jordan’s noises, his scent, the way her boss was reduced to a childlike need. The way, naked, he needed her to look at him a certain way. Sometimes he pulled her hair or bit her nipples. Often, she had a sore groin. These all seemed like they added up to something, proof of her power over him in those moments, proof, at the very least, of her physical form. But not proof, she was realizing, of physical pleasure.

“Fuck,” she breathed.

“Mm,” Birnbaum agreed.

They sat in silence, Birnbaum unwinding his legs and crossing them the other way, and Alma scanning all the times she’d had sex, been naked, been touched, touched herself. It was true that she’d never gotten herself off, but she’d always chalked that up to laziness.

“So I can’t orgasm,” Alma said, in the tone of someone stating the obvious.

Birnbaum puffed his cheeks, then let the air out in a squeaking exhale. “An orgasm is a state of mind,” he said. He pulled a tissue from his pocket and swiped at his nose before offering it to Alma. She touched her face; was she crying? She wasn’t. She began to laugh.

Birnbaum held the tissue up to his mouth, his small round eyes moving quickly over Alma’s face. “All right?” he asked.

She bent over. Her face hurt and her stomach hurt and one of her shoes had a large boomerang-shaped scuff at the toe. “It’s just,” she tried, the laughs coming like heaves now. She smacked herself in the chest to prevent the cough she felt rising up. “I just learned that I have no clitoris from a man. From two men.” She felt hot tears rolling now, snaking down her neck and gathering in the silly collar of her work blouse.

Birnbaum patted her hand, then rose. “I’ll give you some time. You can have the room,” he said, checking his watch, “for the next seven minutes.” He backed out the door and eased it closed with a soft click.

Alma stuck her fingers down the front of her slacks, wormed them inside her underwear. Probed and searched. There was titillation, but that had mainly to do with the thought of being discovered fingering herself in the exam room. On the wall there was a diagram of female anatomy. The nubby clitoris was at the top, tucked into its shroud of labia. Alma put her index finger there and felt only smoothness. A little south was her urethra, according to the diagram. It zinged when she touched it. She remembered a boy in high school who’d touched her there, repeatedly zapping her, laughing as she bucked in discomfort.

She moved professionally through the office and out the door. She rode the elevator with a dowdy woman holding several plastic bags. It was likely that that woman had a clitoris, that she had at some point gotten herself off.

In the car, her body freezing cold against the steaming hot seats, it occurred to Alma that what she’d thought of as her body was simply a state of mind.

Then

For three nights, Alma parked her car around back of the shopping center, in between two dumpsters, and walked a short distance to one end of Jericho. Halfway down the block was Lawrence and Susan Nowak’s house, a pale green box with crooked shutters and a neat yard. A massive charcoal-gray truck was parked in the driveway and the television was always on, limning the curtained windows blue. Alma walked Buckley past the house, to the end of the block, crossed to the other side of the block, and walked back up, where she’d cross again. Repeat. Once, Alma heard raised voices as she passed: Lawrence’s whiny indignance, Susan’s brusque answers. Alma liked Susan, or liked what she’d been able to understand about the woman: that she endured life with a shitty man but wasn’t his victim, that she didn’t seem afraid of him, that she dyed her hair such a bold shade of red. And it was more than that. It was like they had something in common: an understanding about Lawrence that rendered him toothless.

Alma read an article on her phone about how more and more people carried guns, that politicians had been lax half a decade ago about renewing certain regulations, and now it was better to assume everyone was carrying. The article advised against honking your horn, rude gestures, direct confrontation, eye contact. “If you’re a woman,” the article concluded, “be smart.”

Alma felt smart. She was keeping an eye on Lawrence, watching him, and he didn’t even know it. She and Susan could keep him in line. On the fourth night, Alma tried the door of his truck and it opened with a chunky click that sent her and Buckley careening back toward her car. At home, Buckley seemed to be asking her a question with his friendly dog eyes.

“Because,” Alma answered, her voice too loud; why hadn’t she turned on the TV yet? The Nowaks had been watching the ten o’clock news. “I wanted to know if he kept it in his truck.” The article mentioned glove compartments and under the seat as possible keeping spots, but Alma ran before she could check.

The fifth day was a Saturday, one of those creamy yellow spring mornings that promised actual heat. Birds talked over each other outside Alma’s bedroom window. It was best to have a direction, an aim, on days like that. Best not to waste a day like that. Alma loaded Buckley into the car and drove to the shopping center.

Jericho was different in the daytime, more cluttered, noisier. The weather had people out in their yards, kids turning cartwheels, a man washing his car, even an older woman digging around with a trowel in the still-freezing dirt. Alma and Buckley walked slowly up the block and then back down. On the third go-round, as they were across the street and a little south of the Nowaks’, Susan opened the door and hurried down the driveway, pulling the backs of her sandals on as she went. She turned toward the shopping center, walking quickly, waving at the neighbors she passed. Alma wanted to follow her, wanted to cross the street and squint into their window, wanted to flee to her car. It seemed like an opportunity, but for what?

She pulled Buckley toward the shopping center. There was a coffee place there, and a Puerto Rican bakery, and the drugstore—the only options Alma could think Susan may want to visit so early in the day. With a jolt Alma realized she and Susan—or Lawrence—could have been in the drugstore at the same time in the past, browsing for vitamins or discount Easter candy.

Buckley was slowing, and Susan was out of sight. She’d veered toward the bakery. Alma tugged at her dog, but he wanted to get closer to the children, wanted to brush his wet nose against their legs and faces. “Another time,” she said, trying to be firm. But he’d been sighted, and now a group of children was making their way across the street, pumping their short legs.

The Nowaks’ door opened again.

“You,” Lawrence Nowak shouted, charging down the driveway. He slapped the hood of his truck so that the children all jolted and stopped, turned toward him. He said something but it was garbled, something like, “You don’t have a clitoris.” He was in mesh shorts and a crewneck sweater. Alma stared at his feet. They were gnarled, his toes crowding each other. It looked painful. She looked at his face, at the frizzy hair resting on his shoulders. He was looking back at her.

“Mr. Nowak,” Alma said. “Lawrence.” Where was Buckley? The leash was in her hand, wrapped loosely around her legs. She turned, there he was—just out of sight, his tail swishing. The sun was very bright. She turned back to face the man. She wasn’t worried about the gun, she realized, and she felt a smile pull at her face. This was just a man who threw tantrums. Who liked to wave around his toy. What had he said—what was it he just said to the children?

“Get these kids out of my driveway,” Nowak said. The children were melting into her peripheral vision. She felt Buckley push toward them, felt her legs buckle.

She locked her knees, moved the leash from her left hand to her right. She gestured at his bare feet. “Not so tough now, are you?” she asked. Her voice sounded calm, honey-sweet. She took a large step out of the tangled leash, wobbled a bit, planted her other foot just in time.

Nowak crossed his arms over his belly. He looked up, drawing his head back until his Adam’s apple was pointing at Alma. “Jesus Christ,” he said, “Please remove this bitch from my property.” Children tittered and giggled somewhere behind her.

Maybe, Alma thought, he said “forest,” not “clitoris.” Had he said, I know you from the forest? She ran it through her mind a few times until she could hear it, hear him recognize her.

“You know me from the forest,” Alma said.

He lowered his gaze. Beheld her. The leash felt slack. Alma had the sense that if she looked for Buckley, he wouldn't be there. That he only existed because she believed without looking that he was there. She took a deep breath, searching for his scent. It was there—mud, shredded chicken, sun-warmed fur.

“You,” Alma started. The words that were poised on her tongue felt silly. Melodramatic. You aimed your gun at me. You handled my dog roughly. You scared me. “You showed me something,” she said. “Something I didn’t want to see.”

Nowak exploded with laughter, his face utterly changed. He looked delighted, as though she’d offered him a handful of balloons and begun singing the birthday song. The children ran several houses over and began fighting over a garden hose.

Nowak calmed, rubbed his palm against his jaw. “Why’d you look, then?” he purred.

Alma couldn’t tell, looking into his eyes for as long as she could stand it, if he did recognize her. His eyes twinkled with menace, with playfulness. With menace. His hand went to the small of his back. Only then did Alma remember that’s where he’d pulled the gun from at the park.

“Kill,” Alma said. Buckley snapped to alert next to her, his body hardened and straight. The children shrieked as the freezing water erupted from the hose. Alma let go of the leash. “Buckley,” she said, her voice clear, “kill.”

She locked her knees, moved the leash from her left hand to her right. She gestured at his bare feet. “Not so tough now, are you?” she asked. Her voice sounded calm, honey-sweet.

Years Later

Jordan had a dead tree out one bank of windows in his office. Its trunk swayed and, with the windows louvered open, Alma could hear it moan and creak. “That’ll kill someone one day,” she told Jordan, refilling his stapler.

“I hope it falls and crushes Sunil’s Beemer,” Jordan said, with real emotion in his voice. He was bored. Two afternoon meetings had been canceled and he’d already sucked Alma’s toes. This was a danger zone for him, because it gave him time to think, and Jordan had never learned to direct his thoughts, to steer them toward productivity. Instead they flooded in and overwhelmed him. Wondering what to order for dinner held the same emotional weight as wondering what to get his daughter for her birthday. His eyes brimmed with tears; he crumpled important papers.

“You were right,” Alma said. She fit her fingertip in the jaws of the stapler, tried to imagine what a staple through the lunula would feel like. “I don’t have a clitoris.” It was three weeks since the appointment with Birnbaum. She hadn’t wanted to discuss it until right then. The tree groaned. Alma’s toes were moist inside her shoes and she moved them against each other. So much like sex—that moistness, that crowded feeling.

“I’m clitoris-less,” she added. Jordan had his hands on her waist now, his eyes filled with joy. She wondered, with a small amount of fear, if he was going to kiss her. She could smell the protein bowl he’d had for lunch on his breath. She didn’t want him to kiss her, but she wanted him to want to kiss her.

“This is such a relief,” he said. He had a flax seed stuck in his front tooth. “This will save so much time.” He squeezed her hips, then pushed her away. He went around his desk and sat, tapped the Enter key on his laptop to wake it up. He was in work mode now; she was dismissed.

In the hall she passed Marybeth, Sunil’s assistant. Once, as the microwave cooked a frozen pot pie, Alma had confessed to Marybeth about Jordan. That he put appointments on the calendar. That she was expected to keep the appointments. That he touched her. Licked her. “Do you think I should stop?” Alma asked. The microwave beeped: three overly long, overly harsh sounds. Marybeth glanced at it, then pushed some buttons and set the pot pie spinning slowly again.

“What?” she yelled. “It’s hard to hear over this thing.”

“Busy day?” Alma said now.

“Amen,” Marybeth said. She stumbled, the heel of her pump going out from under her, and Alma held out a hand to steady her.

“Oh God, don’t touch me,” Marybeth said, the words running together. She jumped back from Alma’s touch, banging her elbow on the wall.

Alma had seen the same small calendar appointment on Marybeth’s calendar. All the assistants could see each other’s calendars—otherwise, how could meetings be set? Marybeth went in neat—her hair pinned perfectly, the shape of her lips beautifully carved in plum gloss—and came out with her hair down or her lips smeared.

“Bitch,” Alma said.

“Whore,” Marybeth answered, then burst into tears.

*

In the bathroom, Alma helped Marybeth re-pin her hair. She held up a makeup wipe, then wrapped it around her finger to dab at Marybeth’s smeared mouth.

“I’ve been thinking,” Alma said. “About declining my next check-in with Jordan.”

Marybeth met her eye in the mirror. “This is the job,” she said. Slowly, the way a movie robot that had been smashed to smithereens begins pulling its parts toward itself and rebuilding, Marybeth was re-armoring herself. In twenty minutes she’d be stabbing at her salad, its sharp raspberry vinaigrette funk permeating the office, just like any other day.

“I need my job,” Marybeth said. “I have credit card bills.”

“And I don’t?” Alma said. “I actually don’t have credit card bills. But I have other bills.”

“It’s fifteen minutes out of my day,” Marybeth said. “I use that time to meal-plan or think about what I’m going to do this weekend.”

The women stared at each other, each picturing Marybeth disassociating, Sunil over her, his shiny black ponytail bobbing. Alma figured him for a hair-puller, maybe a biter.

“Tell Sunil you’ve started smoking,” Alma said. “Say you need those fifteen minutes for your break.”

“He hates smokers.”

“I know.”

Jordan didn’t; what would turn him off? Alma couldn't imagine. He liked when she was on her period, when she didn’t shave, when he could hear gas bubbles rumbling in her colon.

“If it isn’t us,” Marybeth said, pulling her lip gloss from her pocket, “they’ll just find someone else.” She inhaled sharply, as though the thought had just occurred to her.

Alma nodded, holding Marybeth’s eye. “Deja vu,” she said. She was remembering how sometimes, without looking at Buckley directly, simply sensing his movement, seeing a yellow swishing blur in the corner of her eye, Alma had the sense that she was in the presence of something she had come to believe she understood, but didn’t know, didn’t actually recognize. That their arrangement depended on a series of compromises. That he was pretending right alongside her. That he had a set of teeth she’d never seen, would never have to see.

“Once,” Alma said, grabbing the gloss and running it over her own lips, “I asked my dog to kill someone.”

Marybeth turned to face her. She had, Alma saw, a birthmark in her eye. A little floating turd. Maybe because of this, she had low self-esteem. Alma already knew she herself had low self-esteem. Her shoes and bras were ill-fitting; she did nothing to change this. They were cheap.

“Are you a bad person?” Marybeth whispered. She waved off Alma’s offer to return the lip gloss. “I’m not a bad person,” Marybeth said. “I’m smart, and efficient, and pleasant.” She turned back toward the mirror, watched her hands smooth her blouse.

“I’m good at my job,” she added. She leaned toward Alma. “A team player. That means something.” She turned and left, limping slightly on the ankle she’d twisted.

Alma laughed. The woman was deranged. Still, there was something barbed in her throat. Thinking about Buckley always did that. She’d been so young then. When she thought of herself holding his leash, she saw a bewildered child. Love me, that child seemed to be saying. It radiated off her like cartoon stink lines. Her little apartment, its wobbly desk, her friendly dog, his worried eyes.

For the first time, she wondered if Lawrence Nowak had a physical urge, a need, to pull out the gun. The way Jordan needed the check-ins. She’d thought she was an integral part to the exchange. Nowak saw something in her. Jordan did, too.

But no, she realized, licking all the gloss off her lips, and running the back of her hand across her mouth until it was dry. No. It could have been someone else. Anyone else. Walking through the office, down the hall past the executive offices, noting as she always did the coffee stain in the carpet, Alma felt the selves she’d invented—she’d invented—slough off her. With every step, she was lighter. She weighed less. Less held her down, to the earth. Pushing out the doors and into the covered walkway that led to the parking garage, Alma’s nipples grew hard. She was freezing cold without all those layers.

“Kill,” she’d told Buckley all those years ago. And he’d lunged, snapping at air. There passed a whole lifetime—the sun bright but weak, the tension in her shoulders, her legs and their urge to run, Nowak’s eyes changing, enough of a change in his eyes, rage turning to fear, a news report about a meteor shower she’d see that day or the next, or the next or the next, a perfect milkshake sweating, a decade without kissing, going to work and coming home and going to work and coming home, taking what she was given, the feel of someone else’s skin, the feel of her own, pleasure at the nape of her neck, behind her knees, at the base of her spine, tracing the flower carved into Buckley’s urn—between when she was holding the leash, and when she dropped it.

She had choices—she did. Alma picked up the leash. Buckley led her down the block. At the corner, she turned.

Her car was in the parking garage behind the office. Her footsteps echoed ahead of her, as though she was walking toward herself.

STORY:

Lindsay Hunter is the author of two story collections and three novels. Her latest novel, Hot Springs Drive, was named one of the best thrillers of 2023 by the Washington Post. She lives in Chicago with her family.

*

ART:

Aubrey Hirsch is a writer and comics artist. You can find her work in the Washington Post, Vox, TIME, and elsewhere. You can follow her on instagram: @aubreyhirsch.

Next Tuesday, we’ll feature a bonus interview with Lindsay about this story!